In this chosen family history from the Texas art scene, Xan Murphy asks, “If you’re the only queer person in your family, who will teach you to survive?”

Via writing, found object installation, and performance, JD Pluecker meditates on her biological and chosen families in her exhibitions The Unsettlements. The 2019 show The Unsettlements: Dad, at the Lawndale Art Center in Houston, Texas, addresses Pluecker’s relationship with her father, Tom.

The Unsettlements: Moms, which originated at Artpace San Antonio in 2022, explores Pluecker’s dynamics with her myriad mothers: biological mom Claire, dyke mom Linda, and godmother Barbara Ann. During each manifestation of the traveling exhibition, which also appeared in San Marcos, Texas, and Ontario, Canada, the Houston-based artist engaged in improvisational performances, collectively generating conversations with the public.

Pluecker intersects material histories by arranging constellations of sculptural and found objects in exhibition spaces. One example is a family heirloom teapot from Unsettlements: Moms, which originally communicated pride in legacy. In transit to the Art Gallery of Guelph in Ontario, the teapot broke into pieces. Pluecker displayed the object as if it had shattered there on the gallery floor, signifying broken legacies.

Boys are for Girls

Sometimes we vary from our family. I remember one evening, in my early 20s, when I encountered a mother and her son in a supermarket. The child appeared to be somewhere between four and six. He expressed interest in a pencil bag with red glitter on it, but his mother replied, “glitter is for girls.” I winced and wondered if she was already teaching her child the heteronormative idea that “boys are for girls.”

The psychology of this moment broaches queer theory. For me, the 20th-century philosopher and feminist activist Simone de Beauvoir broke the sound barrier when she said, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.”1 In the second half of the century, Judith Butler further ossified what we understand as queer theory today. Queer theory rejects the inherent link between one’s sex assigned at birth and their expression of gender—which includes sexual orientation. In my experience, realizing my same-sex attraction as a teen forced me to interrogate how I understand gender.

If my existence [as a queer person] is up for debate, I’d rather be the Loch Ness Monster—far more formidable.

Well, to better understand myself, I found that I needed some different tools than those from my adolescence. So far, I knew that queerness was either imaginary or something to feel extremely shameful about—or somehow both, simultaneously. If my existence is up for debate, I’d rather be the Loch Ness Monster—far more formidable. I needed a better explanation.

Fortunately, queer theory is heavily informed by post-structuralist thought, history, and sociology, allowing me to deconstruct my priors. Post-structuralism was a mid-to-late-20th century movement that ricocheted out of France, challenging the world to question assumptions about meaning, truth, and reality. This is exactly what my evangelical, conservative parents were afraid would happen when I left for college.

Admittedly, Riot Grrrl punk music got to me first. Then I read Butler, hooks, Walia, Sontag, Ahmed, de Beauvoir, Foucault, Fromm, Federici, and Freire. I listened to interviews with Andrea Long Chu, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, and Moira Donegan. These researchers and thinkers pushed me to expand my understanding of myself within the world, rather than solely within myself. My parents still have no idea who Judith Butler is.

We Already Know

My queerness influences my worldview, which is an approach that Houston-based artist JD Pluecker and I share. I met Pluecker at Artpace San Antonio in 2022, where I worked in development at the time. Artpace invites one international, one national, and one Texas-based artist thrice yearly to stay in flats, work in studios, and produce admission-free exhibitions. Pluecker was the Texan artist-in-residence that fall. As soon as I saw what she was working on in her studio, I took interest.

Her studio was full of stuff! One table was covered in old, yellowing documents, and another in fabric and embroidery tools and materials. One wall of the studio was lined with books, many of the authors I recognized as 20th-century lesbian and feminist thinkers. Pluecker informed me: “This is the archive of my dyke mom. I drove to Florida and back to pick this up. She was planning to throw it all away if I didn’t come get it.”

Linda L. Anderson is Pluecker’s dyke mom. The two met in 1997 at Yale University. Anderson worked as the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies program’s senior administrative assistant there for 25 years, while organizing with feminist, lesbian, and labor groups on and off campus. Pluecker attended Yale for her B.A. in Ethnicity, Race, and Migration and Women’s and Gender Studies. The two met in Linda’s office at the latter program. Pluecker would come by Anderson’s office to chat, and sometimes Anderson would ask Pluecker to help her tend a plot in the New Haven community garden.

It can be easy to bond with other queer people because we need not explain certain experiences to each other.

During their chats Pluecker revealed that her roommates had discovered her queer sexuality; at the time she identified as a gay man. The roommates psychologically terrorized Pluecker, posting threatening homophobic messages in her dorm room. When she turned to administrators for support, none came. She ended up without a stable and safe place to live. Pluecker told me, “This personally traumatic event compounded with the late 1990s climate of homophobia and transphobia.” The murders of Matthew Shepard and Brandon Teena shook the nation, while violence against countless trans women of color, who largely remain nameless to us now, sent ripples of fear through the queer zeitgeist. Threats turn to fists.

Pluecker’s roommates faced little accountability after forcing her out, but Anderson offered support and advocacy. Through this trial, Pluecker realized that Anderson could teach her how to survive as a queer person in ways that her biological family could not. She turned from the exclusivity of her family tree, to find chosen family.

As I got to know Pluecker and the Texas-born, New York-based artist K8 Hardy, who was also in residence at Artpace in fall 2022, I reflected to them that I did not have any queer elders in my life. I had many thoughtful conversations with Hardy and Pluecker, who are both about fifteen years older than me. They offered me incredible life advice, while I helped them in ways that I could during their residencies. Pluecker sounded out elements of her Artpace installation with me, as we applied relevant theory and life experience to her process. I was reading Sara Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology at the time, which brought me some clarity in our conversations about exploring queer identity.

In getting to know Pluecker, our conversations kept returning to the meaning of queer community. I told her about a friend whom I had known since adolescence, someone who grew up to be a trans man. Wade committed suicide while we were in college. Without hesitation, I blamed his radical evangelical family, who never accepted him for who he was, for his death. I know, because of Wade, that alienation is a killer.

It can be easy to bond with other queer people because we need not explain certain experiences to each other. We already know. Anderson flew in for the opening of Pluecker’s Artpace exhibition. We bonded quickly, falling into our own discussion of the importance of queer community. Well, now Anderson is my dyke mom, too. I talk to her about my dyke problems.

Rhizomes

The connection that I formed with Anderson is absolutely an intended consequence of Pluecker’s practice. Pluecker refers to me as a participant observer; I am a beneficiary of the community-building strategies that she employs, while offering her the desired level of audience participation that her art invites.

Pluecker likens the way her art practice propagates and spreads queer community to rhizomatic root systems. She references post-structuralist thinkers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in her installations, underscoring the movement’s rejection of historical circumstances as natural or innate. At her San Marcos installation, she laid objects from both her biological family and dyke mom atop wide, brown marks on the floor, representative of rhizomatic root systems. The begonias that form these structures are important to Tom, Pluecker’s father. After Tom inherited a begonia from Pluecker’s grandmother, he started distributing the plant’s offspring to his family members.

As a horticulturist of human connection, Pluecker rejects the rigidity of the nuclear family tree, turning to the rhizome.

Pluecker harnesses the history of begonias to reflect on the meaning of family. They are named for Michel Bégon, a French slave trade administrator in 17th-century Haiti. However, Deleuze and Guattari2 have taken up and subverted the rhizomatic root system of the begonia to describe the shape of non-hierarchical approaches to research and theory. A tree with deep root systems, such as a family tree, is shaped by binary, exclusive, and hierarchical power. The family tree’s branches are only shaped by bloodlines. The begonia, on the other hand, grows in a planar, decolonized fashion, allowing for multiplicity in influence and interpretation. The rhizome may be horizontally accessed by anyone.

As a horticulturist of human connection, Pluecker rejects the rigidity of the nuclear family tree, turning to the rhizome. But how does one go about unsettling the structure, testing mutability? Pluecker asks for understanding from her biological family, survival skills from her queer family, and support from both. Straddling those two inputs, she has grafted together a family that meets her needs.

Transgenerations

Pluecker disorients herself—from the family tree, from heterosexuality, and from cisgender identity. She readdresses and repositions her queer interior and exterior. In her The Unsettlements: Moms exhibitions, she nods to her queer identity with an embroidered doorstop, a marker of the proverbial closet—a location of queer alienation and uncertainty—welcoming viewers into a space where she admits that she still does not have all the answers. Her godmother Barbara Ann helped her make this object.

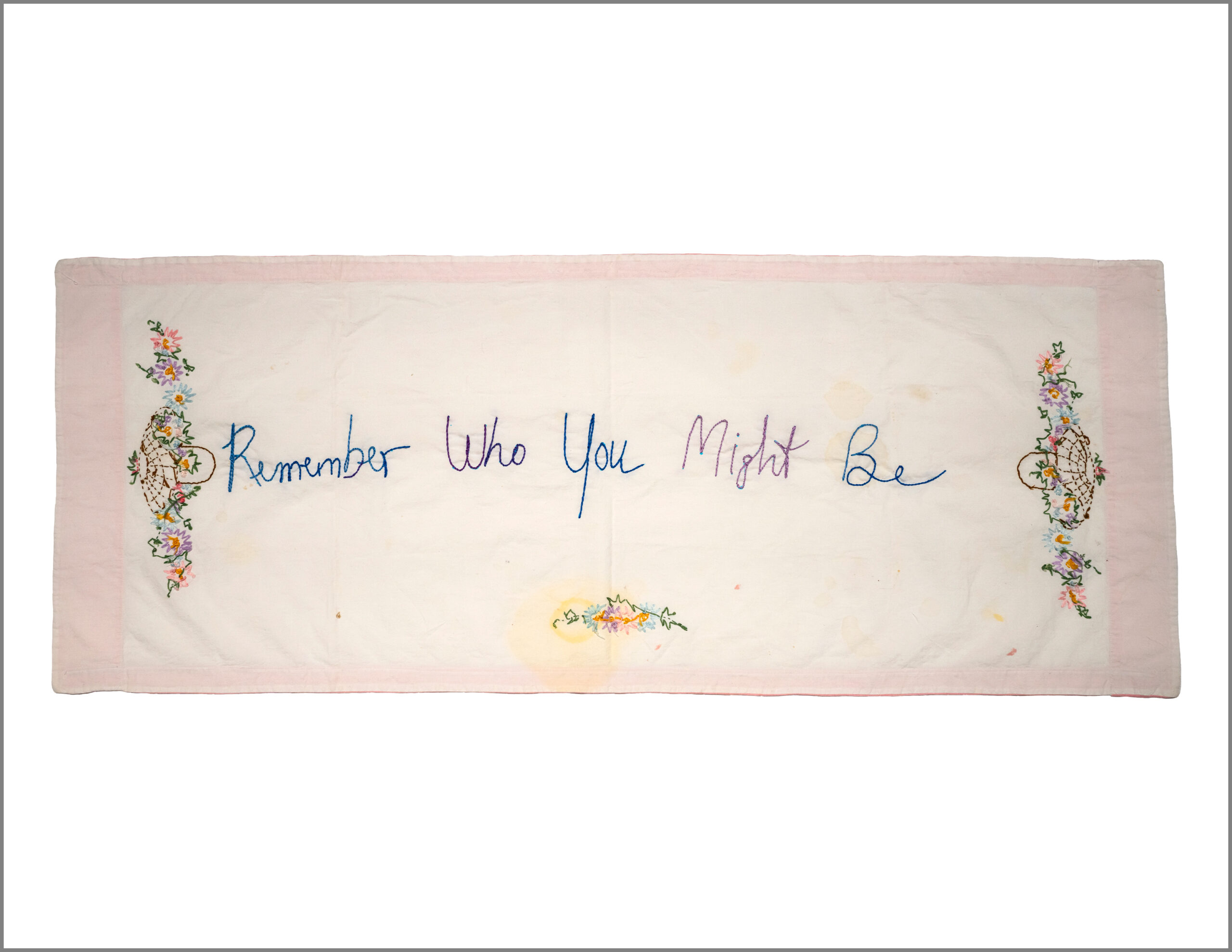

Pluecker’s artistic practice is imbued with a willingness to play with materials until a more corporeal thought presents itself. I think the same is true of how someone experiences a shift in identity. In approaching queer desire, we embrace uncertainty, the possibility for change. Just as Pluecker accepts the fate of the tea pot, she accepts the discomfort in restructuring her family and exploring her transfeminine identity. She contemplates something her mother, Claire, has told her since her youth: “remember who you are.” Pluecker responds—from a grown and agential place—with an embroidery that reads: “remember who you might be.”

In embracing change in her family structure, Pluecker established and maintains an intergenerational relationship with Anderson, which Pluecker characterizes as “transgenerational.” Withal, Pluecker “formulated the term ‘dyke mom’ to establish a sense of queer familiarity with Anderson.” This intentionality of language reaches for an ability to prioritize non-biological relationships, which we are seldom taught to prioritize.

What if you’re the only queer person in your family? Who will teach you how to survive?

The term ”family” in the queer community originates with the homophile movement of the 1950s and 60s.3 Then, “family” operated as a code word for someone who would selectively share with other queer people about their identity, or “come out” to them. “Family” connoted the safety of secrecy, and the purpose of coming out was to find other queer people. Imagining the experiences of people who lived this history, I can feel the transcendence of disappearing into a novel, underground world, where someone new to queer community finds a level of acceptance and joy never thought possible.

My connections to people like Pluecker and Anderson are crucial to my development as a queer person. I myself am disoriented from my family tree. I am estranged from a number of elders in my biological family because of their beliefs about queer people.

“Blood is thicker than water,” we all hear. Yet, the nuclear family does not live up to expectations. Historian Linda Nicholson argues that adherence to the exclusivity of the nuclear family structure is not only ahistorical, but harmful. Emotional burdens cannot fall on one spouse or child. Whatmore, isolation produced by the nuclear family structure allows abusive dynamics to go unchecked.4 What if you’re the only queer person in your family? Who will teach you how to survive?

I feel significantly less alone since taking Pluecker and Anderson on as queer elders. Without a biological reason to connect we, as queer people, still have the power to keep our loved ones afloat. We cannot survive without relationships of deep understanding and care, without learning from each other, without passing between us knowledge of survival, like a passage of rhizome. Alienation may be a killer, but our joy is contagious.

1. De Beauvoir, Simone. The Second Sex. New York, Vintage Books, 1949.

2. Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

3. D’Emilio, John. Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

4. Nicholson, Linda. “The Myth of the Traditional Family.” Feminism and Families, Routledge, 1997.

Editor’s note:

The photo captions in this story do not credit JD Pluecker or her collaborators, nor include information about the media, dimensions, or dates of individual objects. This is sanctioned by all project participants. Xan Murphy offers the following explanation.

“Pluecker refuses to title any segment or object in these installations, and she diligently returns each found object to where it came from, once its role in an installation has been fulfilled. The story behind each object is not made explicit, even for manufactured objects. Installations are to be viewed as a whole, not as groups of individual art objects. No object is for sale.”