MOAB, UT — Museums across Utah are reflecting on the dark history of Japanese American incarceration camps in the state by showcasing a collection of art created by prisoners detained at the Topaz War Relocation Center in Delta, Utah.

Shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the federal government incarcerated over 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Americans of Japanese ancestry in prisons across the country. Thousands were sent to Topaz, including renowned artist Chiura Obata, who founded the improvised Topaz Art School during his one-year imprisonment.

In March, the Moab Museum hosted Obata’s granddaughter, Kimi Hill, to present on her grandfather’s legacy. The talk complemented the museum’s current exhibit, A Moab Prison Camp: Japanese American Incarceration in Grand County, which recounts the largely forgotten history of the Moab Isolation Center, a temporary internment camp for prisoners who were considered “problem inmates.”

“From day one, he knew he would start an art school to lift the spirits of his fellow incarcerees and help them focus on something other than their losses,” said Hill about Obata, whose school enrolled over 600 students and offered dozens of classes in traditional Japanese mediums, such as sumi ink wash painting and ikebana flower arrangement.

After Pearl Harbor, the use of Japanese technology was restricted. So how do you record without radios and cameras?

A Moab Prison Camp, which is on display until June 29, was curated in collaboration with the Utah Museum of Fine Arts in Salt Lake City, where Pictures of Belonging: Miki Hayakawa, Hisako Hibi, and Miné Okubo will show pieces from the Topaz Art School until June 30. Work from both exhibits will be part of a national tour that begins this summer.

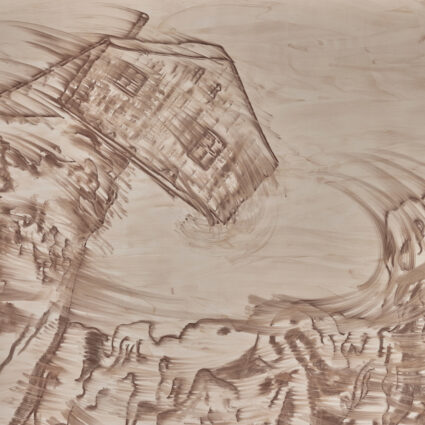

Obata was famed for his landscape watercolors, especially his vibrant vistas of Yosemite. But once wartime detainment began, Obata began sketching the scenes of hostility unfolding in Berkeley, where he lived and worked as an art professor at the University of California. He continued to record daily life in black and white sketches during his incarceration, first at the Tanforan Assembly Center in California and later at Topaz.

“After Pearl Harbor, the use of Japanese technology was restricted,” Hill explained. “So how do you record without radios and cameras? He started sketching everything every day, which was not his typical work.”

In one sketch, his wife, ikebana artist Haruko Kohashi, covers her face against a gust of dusty wind that blows through the cracks of a poorly constructed barrack where the family lived in Topaz. A broom leans against the wall, and behind Kohashi, a trail of footprints shows the futility of sweeping in such a dry and blustery landscape.

Dust was a recurrent motif in Obata’s wartime work, as well as the work of other artists at Topaz. Pictures of Belonging, which spotlights pieces by two other Topaz prisoners — Hisako Hibi and Miné Okubo — includes Okubo’s Wind and Dust, a portrait of three prisoners huddled against a turbulent storm.

While at Topaz, landscape painting took on a new meaning for Obata, who was incarcerated with nearly 10,000 other prisoners within one square mile demarcated by a barbed wire fence.

“What was beyond the fence was the mountains,” Hill said, referring to the Pahvant Mountains that frequently appear in Obata’s landscape watercolors from this time. “He was always looking at those mountains.”

“Looking at the desert sky was a favorite pastime of my grandfather’s,” Hill said. “Looking out and away from all their troubles and all this trauma.”

In one of his most famous prison paintings, Topaz War Relocation Center by Moonlight, a full moon washes the landscape in silver, erasing the horizon and collapsing the boundary between ground and sky. The barracks appear suspended in clouds of dust.

“It’s a very simple composition with these clouds that almost look like roads leading to the moon,” Hill said. “It’s saying: This time will pass, and what’s important is maintaining your hope. It’s saying: that moon is your future.”

“He would tell his students: unless you have a connection with nature, you can’t have happiness, and to find that connection with nature, you have to throw your spirit and body right into nature’s heart,” Hill said. “That’s why he would seek these extreme landscapes where it’s easy to do that—all you have to do is open your eyes.”