The Roswell Artist-in-Residence Program, established in 1967, gives worldwide artists an entire year of rent-free creation, monthly stipends, support for artists with children, large spaces, and beautiful light in southeastern New Mexico.

ROSWELL, NM—“The thing is, of course, it’s a gift of time. When you have the whole year and you don’t need to worry about bills and things, it’s like your own ocean. You’re in your own ocean.”

This is how Masha Sha, an artist in the 2020-2021 Roswell Artist-in-Residence Program (RAiR), describes her residency experience on the high plains of Roswell, New Mexico, during a recent phone call.

Weeks earlier, I had run into Sha at the Anderson Museum of Contemporary Art (AMoCA) in Roswell while driving back to Denver from Marfa. She greeted me at the door and was unmistakably familiar. It took us a couple of minutes to figure out that we met a few years earlier at GEORGIA, the garage gallery I founded in Denver. I mention this because, despite the hundreds of miles between southwestern towns, you still run into people you know—a lot.

AMoCA is a wild and eclectic collection. And it asks you for some of that limited resource Sha mentions: time.

AMoCA is large. It bursts with hundreds of works of art in just about every medium and in as many styles. Some of my favorites include Diane Marsh’s lush oil portraits; Luis Jimenez’s voluptuous drawings; a standing vessel weaved from seagrass and rags by Rebecca Davis; a mesmerizing diorama of an ordinary room installed inside the wall—complete with peephole—by Erica Bailey; and a minimal, meditative painting by Johnnie Winona Ross that seems to vibrate.

The collection is comprised of pieces created by the residents of the long-running residency, and I admit I was expecting it to feel like a storage facility. But it was thrilling; intense but thrilling.

Like the best of these feral collections—the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston and the old Getty Villa in Malibu—everything hangs together as if with magic. The textiles resonate with the three-dimensional objects with intuitive ease. It is how I like my curation, abiding the logic of a poem rather than that of an equation.

I learn that the Roswell Artist-in-Residence Foundation purchases a piece of work (sometimes more than one) from each resident for AMoCA’s collection, The museum is only missing representation from five of the 259 artists they’ve hosted since the residency began in 1967 when Donald B. Anderson, an oil and gas businessman and artist, founded the program. Anderson wanted an inclusive residency set in the tranquil Southwest, or, in Sha’s words: “this beautiful open space and light.”

“It’s like a little life in itself,” says Sha, “and it seems like it will never end. And only you really understand it’s ending maybe the last two weeks of the residency. The luxury of a residency is to not know what time it is, what day of the week it is, what month it is, this complete luxury of being lost on the scale of time.”

I could hear it in her voice, it was ending. (She was in the last weeks of her residency when we spoke.) RAiR gives its six fellows a year of rent-free housing, ample studio space, and a monthly stipend. It’s one of the more generous residencies for visual artists in the country that I have come across, especially because they support artists with children—offering living spaces large enough for families and additional financial support.

“It’s amazing because I can have a place to work with my child really close and influence him and share with him everything,” she says. “It’s a gift because you can be with your child the whole year.”

As I leave the museum, Sha tells me her show, unsaid, is up for two more days at the Roswell Museum and Art Center. (Yes, Roswell has two art museums!) The exhibition features work she made during the residency.

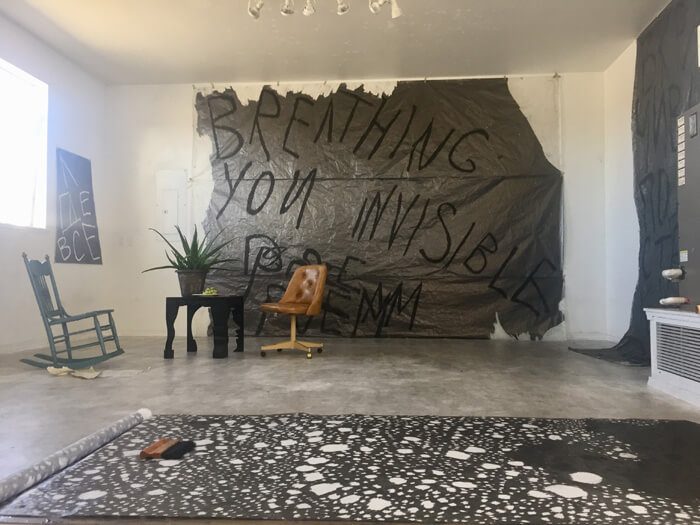

I drive across town to see it and find that the work in unsaid is huge, breathtaking, defiant, fragile. Sha lines the gallery space with wall-sized drawings of words in graphite and lead on tracing paper. The words are scrawled across the paper. The letters are taller than they are wide with sharp edges that appear to pierce the thin paper—they do in fact. The pressure of the marks tears the paper to pieces in places.

In Shifts, the word TRUST appears segmented and misaligned as the swaths of paper that make up the entire work are affixed together a bit askew on the wall. The way it is written is how one might think the word “trust,” like graffiti inside one’s skull. The whole piece is 111 by 183 inches—so large you could wrap two lovers in it.

I feel the other pieces shouting at me as I walk by: HEAD WIND, disappearing, вкрадчивъм подстрекатеаъ (Sha is Russian and this one translates to “sneaky trickster”). They are imposing. The space they take up on the walls is analogous to how much space they take up in my psyche.

Anderson, the artist and oil tycoon who established the program, called the residency “a gift of time.” But the residency is also a gift of space. Both things, time and space, we are given at birth, and both we seem to constantly pursue.

“Before coming here,” Sha says, “I would make drawings bigger than my apartment. And sometimes, I would have to line them on the floor between furniture and… I couldn’t even photograph them because the apartment was smaller than my drawings. Here, it was amazing for me just to have this floor and this beautiful light.”

The Roswell residencies are staggered throughout the year. Artist Eric J. Garcia is the most recent arrival. March 15, 2022 is the deadline for the next round of residency applications. Good luck!