Amanda Dannáe Romero and sheri crider discuss the Sanitary Tortilla Factory exhibition featuring the work of system-impacted youth and the role of art in creating social change in New Mexico.

As part of her year-long residency with Artists At Work, the New Mexico-based artist and musician Amanda Dannáe Romero has worked with incarcerated youth to enrich the arts education of the Gordon Bernell Charter School in Albuquerque, a school that serves students at the Metropolitan Detention Center. The project culminates with an upcoming exhibition titled One Day Closer to Home that’s on view February 2–23, 2024, at Sanitary Tortilla Factory in downtown Albuquerque, a nonprofit working to support civic-minded projects. The show spans drawings, portraits, music, zines, and other works that explore the meaning of “home” and the impact of the carceral state on affected kids.

Artists At Work is an initiative spearheaded by the New York- and London-based social impact incubator The Office Performing Arts + Film, which is funded by the Mellon Foundation and has previously supported projects by artists like William Kentridge, Carrie Mae Weems, Angelique Kidjo, and others. Romero was one of three artists selected for the organization’s 2022-2023 New Mexico Borderlands Region cohort, and, alongside the artist sheri crider, the founder of Sanitary Tortilla Factory, or STF, worked with the city of Albuquerque’s arts and culture department to complete the project, with support from the Youth Civic Infrastructure Fund.

In a conversation with Southwest Contemporary, Romero and crider discuss the making and the future of the project.

SWC: What sparked your collaboration and collective interest in working with system-impacted youth?

Romero: We started working together somewhere around 2018. I was interested in the work sheri was doing in the community and was pretty familiar with the STF space, where I was fortunate to get a studio. We shared interests in our respective practices, and her long-term goals for STF informed my application for the residency.

Crider: I’ve historically worked with incarcerated youth and formerly incarcerated people because I am a previously incarcerated person and came to art through the back door—with no idea about the elite structures of the art world or the silo of academia. STF was founded as a resource for the community because there wasn’t a space like it in Albuquerque before. New Mexico is full of systemic failures in education and criminal justice, and the pandemic in particular dismantled many [arts and social justice] organizations.

What was your process like? And what were some challenges you encountered throughout the project?

Crider: We spent a good half of Amanda’s residency trying to get somebody to work with us because, again, so many connections were lost during the pandemic. Then, as an instructor, you’re subjected to all these unpredictable hurdles. You’re a victim to whatever is happening—whether it be staffing shortages or lack of facilities. You just have no power.

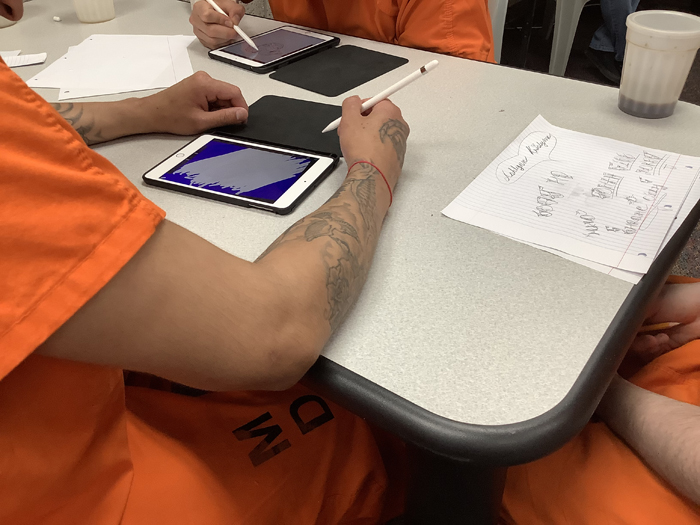

Romero: Of course, there’s the obvious items that are prohibited, so there’s some logistical issues in terms of what we’re allowed to bring inside. We scale things down and adapt. Right now, we’re going back to basics, with pens and pencils. We were working with markers, but then the markers proved to be an issue. We’re fortunate to be able to bring a laptop and a recording device, so that’s a great avenue of expression for students interested in music.

How many students do you typically work with? How many of their works will be included in the exhibition?

Romero: At first, it was around the same amount of students for each class, so I was seeing the same faces for the most part, or around fifteen students. Now, the classes are almost double the size. Next week, for example, I’ll be going back and forth between two classes. Sometimes there’s a lack of continuity because students will shift units, get transferred to other facilities, or get released. But, for the most part, the works in the show are from students who have been there on a weekly basis since the program has been available. Regardless, pretty much every student who has passed through one of the classes will have had a hand in one of the projects that will be shown.

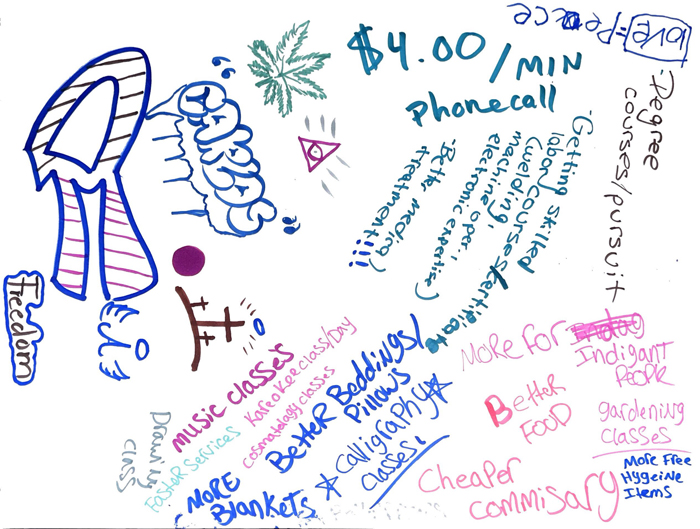

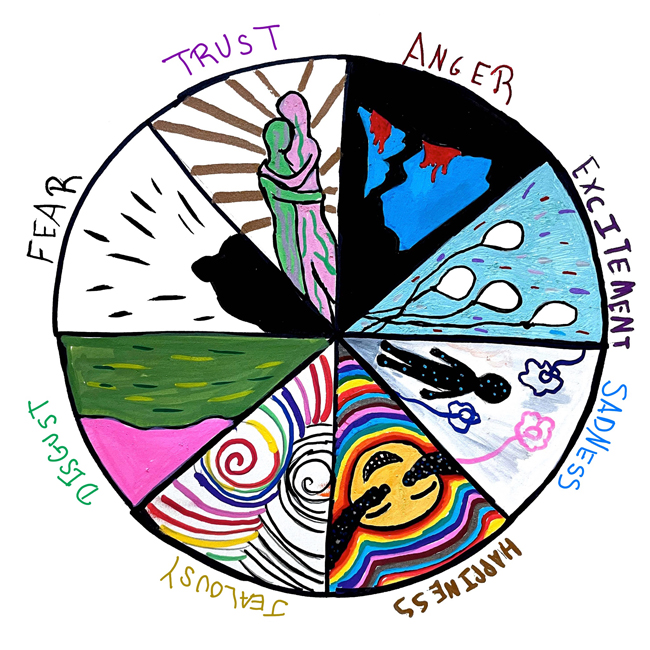

What are some overarching themes that the students explored in their works, and how did that factor into the title of the exhibition?

Romero: The title comes from one of the first projects I did with the students, which was memorable. We did a workshop where we made small zines—a flipbook that you could fit in your pocket. I asked them if they wanted someone outside to know about their experience here, and there were so many profound responses. We made a list of potential titles, and this one came from one of the students. It just summed up the scope of the entire project, and themes like abolition and justice for incarcerated people.

How do you believe that the program can positively serve system-impacted teens?

Romero: It’s not about an end goal or a finished body of work, but it’s more about thinking about art as a means for people to form their own perspective and form their own narratives about themselves. That sense of empowerment is something that they can take away from this class and bring back into the community. There are often so many things stacked against them, and this allows them to be successful in their own right, within a system that is oftentimes designed with the opposite intention.

As you mentioned, the project was born from the need to reinstate some of the programs and initiatives that were lost during the pandemic. How will the project continue beyond the residency and exhibition?

Crider: It’s been an incredible experience to work with the Gordon Bernell Charter School, and it’s created an opportunity to continue working with them, which we’re excited about. We’re hoping to start working with young women who are incarcerated, but it’s a slow process to get into these facilities. You have to have someone who’s already there doing some existing groundwork. Arts programming and arts education are equity issues, particularly in New Mexico. It’s within the school system, too, not just within the carceral state.