Cedra Wood and Nina Elder’s two-person exhibition Perplexities acknowledges complexity and the unaccountable and meets it with one kind of certainty: deeply considered and well-executed art.

Cedra Wood and Nina Elder: Perplexities

April 8—29, 2023

Pie Projects, Santa Fe

Social ecology is common ground in the work of Nina Elder and Cedra Wood in their two-artist exhibition, Perplexities. Both artists explore pattern in nature, the grandeur of tiny things, human interaction with the natural world, social and environmental justice, and the liminal realm, the overlooked or unapparent, things just beyond passive awareness.

The artists are friends, both wanderers and veterans of residencies in faraway places. Their common experience offers an unintentional synchronistic collaboration in Elder’s graphite drawing Seafoam and Snarl (2023), based on a tangled mess of kelp and tidal effluvia found on the shore of Kachemak Bay, Alaska, and Wood’s rope-bound, human-scale form Visitation (Great Lakes) (2023), conceived on the shores of Lake Michigan. Wood’s figure may be seen emerging from Elder’s shoreline.

In Visitation (Great Lakes), cinnamon-toned sisal ropes gather from loose ends on the floor to climb a welded steel armature to form the woven skin of a gesturing figure. The tangles at the base give a marine feeling contributing to the sense that the visitor has arisen from the deep. The specter is not threatening, and seems to bow, but not with submission. The body language, with the grace of a weeping atlas cedar, elicits an empathetic acknowledgment. It seems a player in a tragedy that is staged on the edge of hazard, an outlier.

The companion painting, The Story Itself is a Ghost (Great Lakes) (2023), tiny by comparison, is so perfectly lit that the sunset in the distance behind the visitor seems to illuminate the painting from within and haunts the wall around it with a spectral halo. In this scene the artist is asking, “How can we know what other beings know?”

Wood’s painting Child Ballad 68 Young Hunting (2019), presents a dark dome-shaped object which seems to be emerging from a pond, but the verses of the 18th-century ballad the painting is based on, combined with a closer look, reveal the cranial form to be a floating loaf of bread. The song tells the story of a young man stabbed by his lover in a jealous rage, the corpse dumped in the river. A talking bird describes the device that will locate the body: the loaf surmounted by a candle; the flame fed by the breath of the dead. As painted by Wood, the loaf has a primordial and ambiguous presence, perhaps a subterranean embodiment forming a connection to the first murder, and by natural selection, the first song.

The central object in Wood’s three-part Fishbone Beast / Accumulated Matter (2019, 2022) tableau is a sculpture made of fishbone from seasonal die-off gathered near the receding waters of the Salton Sea in California. It is hollow and wearable, suggesting that a potential performative element is part of the interplay with the portrait and painting that flank it. The portrait is close up, mostly obscuring the space behind the figure, while the painting gives place and context, a shoreline. The multiple viewpoints familiarize the creature, and invite softening feelings. A human wearing the fishbone cowl would be blind and have difficulty breathing, as if walking a mile in the body of the beast.

Elder’s drawings seem a whispered conversation between Elder the artist and Elder the scientist, combining a microscopic focus with a pencil touch that is painstaking and light, in a deliberate caress that chromatically embraces the gray areas that come with her non-binary thinking. Her Glass of Water (2023), allows the mineral-marked or otherwise variegated-by-reflection planes of the glass to break the lights and darks into images that invite a fire-lit cave painting gaze.

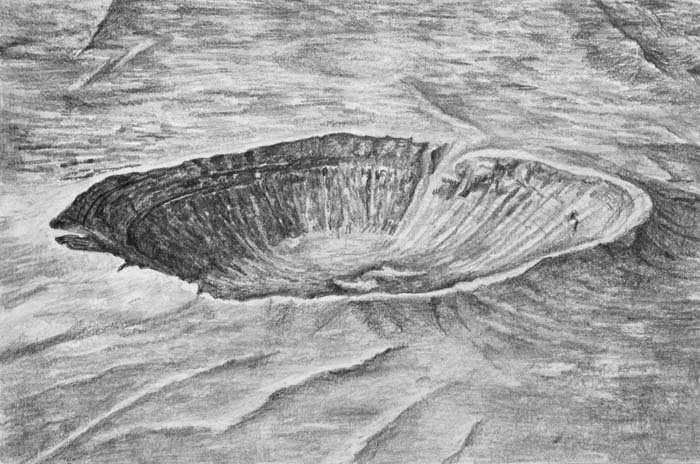

Like Robbe-Grillet’s phenomenological short stories, which can make the description of a coffee pot sitting on a tablecloth terrifying, Elder’s intimate disclosures offer a fascination with things as they are, across a range of subtle feelings that simply come with attentive observation: rendering a crater tender; a skull planetary; and a granular-metric array of raindrops whimsical. A crater is tender if you feel the earth alive, even fragile if seen from enough distance. This is the opposite of anthropomorphism—the three scales evident in these three views of the world are one in the other and imply an infinitude of such relationships.

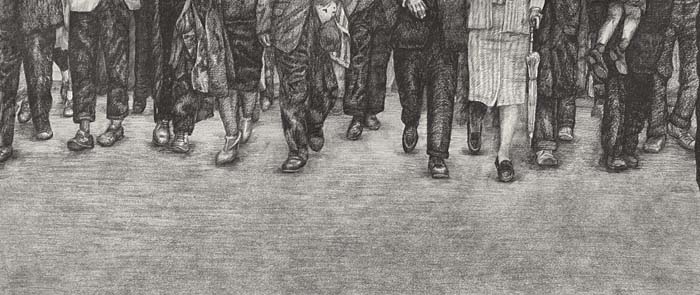

Elder’s photo-derived drawing, Selma (2023), documents the moment in 1965 when voting rights marchers in Selma, Alabama crossed the line onto a 1940s bridge named for a Confederate general and KKK Grand Dragon elected to the US Senate in 1897. The legacy of the bridge was transformed that day to a symbol of the civil rights movement that led to voting rights legislation made official six months later.

The drawing reframes the moment the line was crossed. By focusing solely on the marchers’ feet, Elder foregrounds their courage and determination and amplifies the sound of their advance. The sound of resistance that is ongoing.

Perplexities acknowledges complexity and the unaccountable and meets it with one kind of certainty: deeply considered and well-executed art.