Artist Hong Hong works in papermaking, an art she defines as improvisatory choreography. Her latest work at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft seems to bridge earth and sky.

If the sky could look down from its greatest height and interpret our landscape, the rivers would be rivulets, the roads thin. Yet, the sky is mostly indifferent. Even as it storms, it is seemingly unseeing. It does not look down.

However the long list of tall buildings breaks records, or we beat our chests and call out to the heavens for divine aid, we get little response. When the cold makes breath visible, or we take off in an airplane, we still don’t really know the sky.

In writings the papermaker Hong Hong shared with me via email during our separate quarantines, she offered, “The sky is a taciturn blue forever passing over everyone. Perhaps the sky, like god, can only belong to us because of silence.”

In works she also created this past year as an artist-in-residence at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, Hong seems to connect earth and sky, finding both all-encompassing and liberatingly quiet. She writes, “Across numerous cultures, land is seen as an extension of a magical being. In Chinese mythology, Pangu is a giant sleeping inside an egg. When he wakes up, he swings his ax to separate the sky from the earth. He holds up the sky with his arms for 18,000 years, pushing it slowly away from the soil a few meters each day. After he dies, his breath becomes the wind; his voice, thunder; his knees, mountains; his left eye, the sun.”

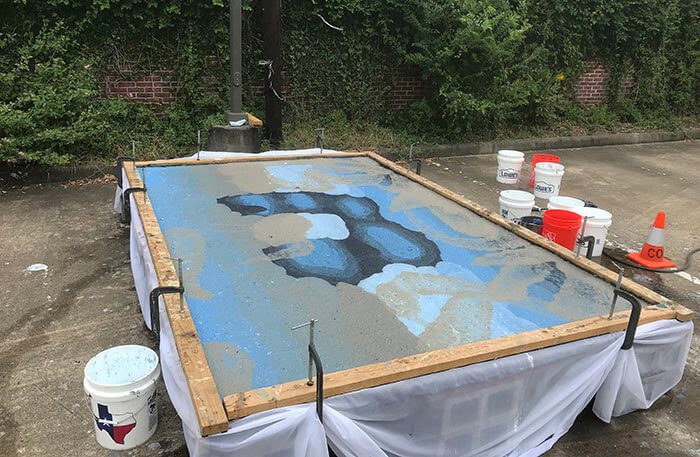

Hong works from a place reminiscent of Pangu’s 18,000-year heave, before earth and sky were so separate. She opens up possibilities for connection between earth and sky, working outdoors with a giant papermaking set-up, a twelve-by-eight foot, wood-framed wire screen. She defines papermaking as improvisatory choreography. She begins with the bark (cooking it, pounding it, blending it), then dyes it, and composes it in pulp form on the screen. She scoops, splashes, drizzles, and layers the paper pulp on the screen. She might adjust her composition using the spray of a hose or a stick. The paper accumulates evidence of her actions as she creates and abrades it. In her hands, handmade paper, usually thick, is further textured. She also leaves the paper-in-progress open to the elements, welcoming rain and wind, letting the paper collect leaves, dust flecks, and hairs.

Hong’s process is nomadic. Each place she lands (Texas, Ohio, Connecticut, New Hampshire, New York, Vermont…), she assembles her supplies: lumber, watering cans, squeegees, pots, jars, measuring cups, soda ash (for dissolving plant fiber to make paper pulp), fiber-reactive dyes, non-iodized salt (also for dyeing), blenders, spatulas, clamps. For pulp, she uses construction paper, kozo (mulberry) bark, or handmade paper recycled from her previous artworks. After the sun has dried the variegated paper and it comes off the screen, she might cut the paper and arrange it. She will often create one complete composition by installing some paper on the floor right up against the wall and hanging more paper low on the wall, touching the floor or almost touching the floor.

She opens up possibilities for connection between earth and sky.

Importantly, these paper pieces are temporary. Hong photographs them but does not preserve them completely. She wants the parts to be reusable and for them to fade and dissolve. She writes: “A sheet of paper and a boulder both accept and absorb the gestures of tenderness, neglect, devotion, and violence. This porousness eventually leads to material instability and demise. In this way, all things continuously engage with the act of writing their own histories.”

The bold shapes in Hong’s recent abstract paper works suggest aerial views of mesas, clouds, lightning, mutating cellular orbs, sediment in water, or dark planets. They’re Prussian Blue, deep black, grey, and parchment white. The shapes have rounded or hazy edges as if they could move, or we are seeing them from some distance. Their scale is uncertain. If we are looking at landscapes, they could be planet-sized, human-sized, or interstellar.

I was meant to meet Hong in person twice. She was going to come to Nevada for a papermaking workshop, but her schedule was too packed with residencies and exhibitions. Then, this past fall, she was going to come to give a talk and visit with students at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Instead, because of COVID-19, we coordinated a virtual visit, and she and I began to correspond about her work, though I’ve never seen it in person. Hong told me that she had read and liked the 1947 collection of writings, Gravity and Grace, by French mystic Simone Weil.

For my part, I find Weil’s thinking a twisty and surprising path, unsettling maybe, but useful in understanding Hong’s work, it’s graceful and restrained fullness. A short ascetic chapter in Gravity and Grace titled “Imagination Which Fills the Void” calls imagination a liar and encourages the reader to avoid it, to keep it from filling voids. Weil acknowledges that gaps and voids produce bitterness and that humans imagine in order to compensate for disappointment or cope with suffering and death. But, she compares imagination to money. She calls it a filler, one-dimensional, a base diversion.

Rather than be distracted, if we could keep imagination away, maybe we could face the holes and fissures within ourselves. Maybe we could accept them and achieve a greater dimensionality of experience akin to enlightenment. Weil writes, “We must continually suspend the work of the imagination filling the void within ourselves. If we accept no matter what void, what stroke of fate can prevent us from loving the universe? We have the assurance that, come what may, the universe is full.”

Hong’s Ladle for Beasts Lapping at a Moon-Shaped Pool II (2020) on the wall has four dominant black shapes that could almost be two pairs of partial footprints on white and cyan rectangles. I want to call the rectangles mats. On the ground are allied echoes of these mats, striated blue and black with white patches at the tops and bottoms. This piece references an earlier work, the first Ladle for Beasts Lapping at a Moon-Shaped Pool. It is the same height but almost twice as long. Looking at its central blue expanse gives the sensation of looking into a massive aquarium tank.

Device for a Child Standing at the Mouth of a Labyrinth II (2020) uses two of the same mats from Ladle II, but this time, one is on the wall, one is on the ground rotated 180 degrees. The dominant shape is a white, rough-hewn right triangle with no pointy top—a wintry cliff to climb or an avalanche of snow. On the wall in Device, there is one black oblong on a sky blue background next to two smaller sky blue oblongs on a black background, smaller and more like kidney beans. On the ground, a blue stripe and magenta side flaps might have just opened to reveal a trap door of some sort.

Standing, waiting, looking in, or stepping back and looking up, getting a drink by taking small licks, being detached, open to chance, but possibly about to get lost, contemplating a blur, a hole, or is it a pool, a canyon, a breath, or a portal reverberating? Considering Hong’s work, one might think of everything and also of nothing. And that nothingness is everything. It’s generous and robust. To quote Weil again, “I must love being nothing. How horrible it would be if I were something! I must love my nothingness, love being a nothingness.”