H. Joe Waldrum (1934-2003): Retrospective

October 12, 2019–January 26, 2020

Rio Bravo Fine Art, Truth or Consequences

Harold Joe Waldrum, who spent a good chunk of his visual-art career depicting the adobe churches of northern New Mexico, wasn’t the first artist who worshipped the act of portraying places of worship. Waldrum, not a religious man by any means, also wasn’t the only Anglo-American creative to fall in love with the Spanish culture of New Mexico or the sole artist to split his time between Taos and New York City, which he did for a spell in the 1970s. The quirky Waldrum also can’t lay claim to pioneering the art of working in the nude or being the only artist to fatally wound a man in a gunfight, though he definitely distanced himself from the masses with that one.

Diverging from traditionalism and even abstract expressionism, two styles he eschewed after pivoting from high school band teacher and music arranger in Kansas to full-time professional visual artist, the self-described “romantic-formalist” beautified mudbrick buildings in the Southwest like no other.

The exhibition, H. Joe Waldrum: Retrospective, at Rio Bravo Fine Art is a first-of-its-kind overview of works from the H. Joe Waldrum Trust, which inherited a majority of his pieces after his estate closed in 2014. The exhibition, curated by Eduardo Alicea-Moreno—director and president of Rio Bravo Fine Art, the Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, gallery Waldrum founded shortly before his unexpected death in 2003—showcases the depth and breadth of Waldrum’s high-volume career.

The impressive scope of Waldrum’s visual-art vocation includes not only paintings, prints, and linocuts of adobe churches but also a drop-dead gorgeous series of Polaroids, a handful of unfinished paintings, and a large body of abstract paintings in his Window series. Also included in the retrospective is a bronze sculpture of Waldrum painting naked by artist Reynaldo Rivera.

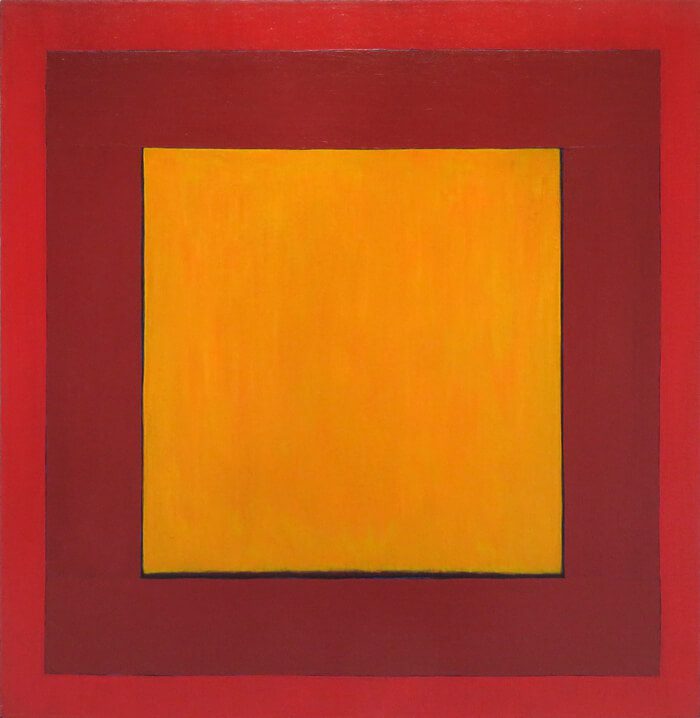

In the early 1970s, the Savoy, Texas–born Waldrum moved to Tesuque and then to the Taos area, where he began to deconstruct his previous straight-ahead compositional élan. (Waldrum would later live an off-the-grid, art-making lifestyle on a ranch near Socorro.) A number of pieces in the Window and triptych series recall Mark Rothko’s bundles of muted and glowing colors. Others, such as La casa vermellón, look like a Rothko painting under the spell of Paul Klee’s vibrant color palette, as the concentric squares of orange and purple create a three-dimensional illusion on the two-dimensional acrylic-on-linen canvas.

As in the Window series, the viewer is never allowed a glimpse through the window of one of Waldrum’s figurative-yet-melty adobe cathedrals. Instead, Waldrum was laser-focused on the structure—you’ll never find evidence of human existence in an artwork by Joe Waldrum (the nom de guerre he preferred later in his life). Northern New Mexico’s churches were like Egyptian pyramids to him, and his artworks show how the obstinate facades of the architectural Godzillas interacted with color, shadows, contrast, and the potent, suspenseful la luz of New Mexico.

In works such as La morada de Don Fernando de Taos (Waldrum titled the majority of his works in Spanish), light and shadow both fit into and fight with one another as they compete to illuminate or shroud the circa-1830s holy site that Waldrum illustrates in a brooding desert red. Bell Tower at Corrales is a side-angled view of what appears to be a traditional Christian cross, but due to the catawampus gotcha perspective, comes across as the Zia symbol.

Waldrum also photographed church windows and flowers during all hours of the day with a Polaroid SX-70 in order to use the images as references while he wintered in New York City. In 1976, Waldrum mortally wounded a man while protecting his Pecos-area studio from thieves. A day after hightailing the scene in a van pockmarked with bullets, Waldrum returned to his property in the village of El Gusano to find his paintings, drawings, musical scores, and the entire studio building torched into ashes. The part-time move to New York was a necessity in order to get the heck away from relatives of the man he killed.

Though the reference images weren’t necessarily captured with public consumption in mind, one can see the titanic role light and color played in Waldrum’s compositions and how he could make art even when that wasn’t the end goal. These images also offer the only peek through a Waldrum window—this time into the mind of the overlooked artist himself.