Arizona-based artist Farraday Newsome’s studio extends into her high-desert garden, sprouting ideas for intricate ceramics about nature’s self-perpetuating systems.

A ceramic lamppost surrounded by desert plants beckons those who wander down Indigo Street, an off-the-beaten-path road in Mesa, Arizona, where artist Farraday Newsome creates ceramic forms and paintings that reflect her deep connections to the natural world. Raised amid the California redwoods, she’s spent decades in the Sonoran desert, sharing studio space with husband and fellow artist Jeff Reich.

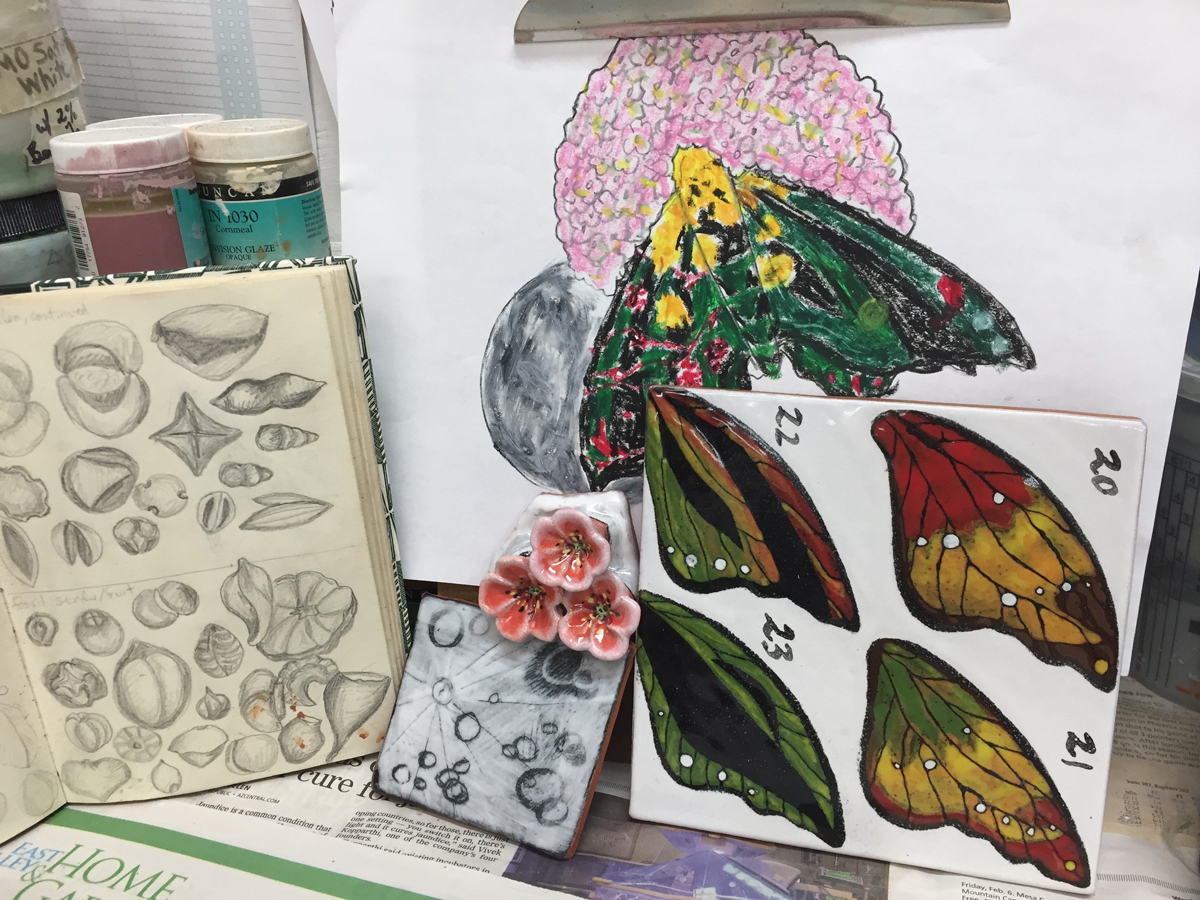

Inside the studio, her desk is topped with containers of ceramic glaze, ideas, and designs written on small recycled papers held together by binder clips, and other necessities. Below, she’s filled drawers and boxes with samples of the colors that infuse her work—the vibrant oranges and yellows of citrus, the soft pinks of blooming flora, the rustic browns of pine cones, the cool blues of water and sky.

Across the room, there’s a particularly striking piece of Newsome’s work—an unfinished vessel resembling a uterus with its curved horns. “I like to explore personal metaphoric associations and my own emotional reactions to being female in a biological world, but I try to avoid making my work too anthropomorphic,” Newsome says. “I want to take fertility and nurturing beyond the realm of human reproduction so it reflects nature itself as an infinitely beautiful, self-perpetuating system.”

The couple’s studio sits on the west end of their ranch-style home, but their creativity spills into other spaces—including a habitat behind the house they created to nurture wildlife, house their vegetable garden, showcase sculpture, and gather with friends.

During a late February studio visit, the artists grabbed their sun hats and walked me through their expansive backyard landscape, pointing out particular artworks, pausing to add water to a birdbath, checking on a grove of newly planted trees, and picking snow peas growing in trellises near tomato plants, rows of arugula, and other foods that support their vegan diet.

Seeing sunlight fall across variegated rocks and stalks of desert plants, it’s apparent that many of their shapes and textures are manifest in the ceramics that flow from these artists’ hands. “Making art has so many parallels with gardening,” Newsome says, reflecting on lessons learned about using native and non-native species. “Plants have a way of adapting, and a lot of it is just figuring out what works.”

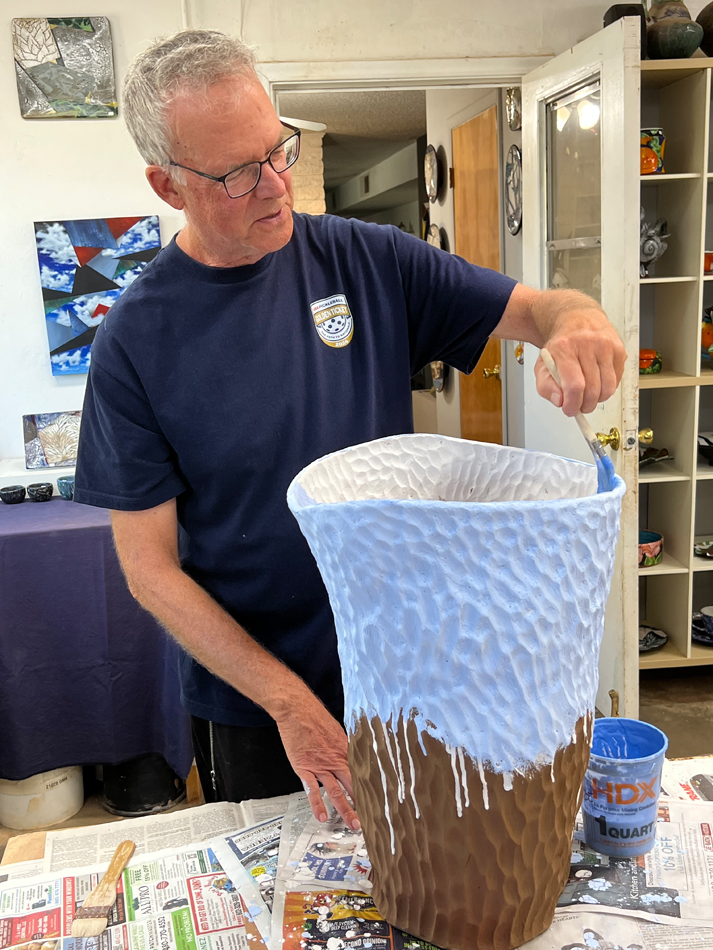

Back inside, Reich’s geometric ceramic pieces, which also channel his earlier study of architecture, cover most of the studio’s working surfaces. That’s because Newsome’s most recent body of work was on view at Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum, in the solo exhibition Memento Vitae, My Body is Your Nest.

The museum displayed dozens of platters, vessels, and other forms that incorporate subjects drawn from nature and manmade objects that carry symbolic weight. Think pomegranates, seashells, snakes, butterflies, and deer—but also watches, eyeglasses, and dice.

Most were made between 2021 and 2024, first amid COVID-19 lockdowns, and later, while caring for her ailing mother and mourning her death.

“My newer body of work reflects my deep interest in the intelligent, lush beauty of nature and its brilliant, creative strategies for propagation,” Farraday explains. “But it’s also exploring the cycles of life and death.”

Lately, she’s been working on final revisions for a catalogue that will showcase a lot of these pieces, working at the computer in a home office filled with books and art that’s adjacent to a small room where the couple photographs and documents their work—and stores household basics like the vacuum cleaner.

There’s a transition space between the living areas and studio where Newsome and Reich display some of their artworks. On any given day, they might have wall works laid out by a fireplace, cups lined up across a shelf, sculptures set atop plinths, and paintings hung on various walls. It’s an easy way to share art with collectors, host open houses, and store finished pieces.

Throughout the house, works by other artists dot various walls, counters, and shelves, hinting at the way this creative couple feels connected to both local emerging artists and the established artists who’ve inspired or mentored them. Nowadays, Reich says, they’re thinking about their own legacy—not just making and exhibiting new art but also working to place existing works in a variety of museum collections.

As for the studio, Newsome says they hope it’ll be acquired one day by a program that’s dedicated to the ceramic arts, where students can learn and artists can undertake creative residencies. In the meantime, it’s a thriving, ever-evolving embodiment of the ways they’ve married nature and art.