Peters Projects, Santa Fe

June 8 – August 25, 2018

Time, as many a physicist, mystic, and indigenous American can tell you, is not linear, despite our human perception of it as such. Everywhen, the title Cara Romero chose for her exhibition at Peters Projects, is a term the artist uses to describe a cyclical notion of time as “everything, all the time, always.” Once Einstein’s theories of relativity shattered our human concept of linear time, physicists began to consider that there is no such thing as time. It’s possible that Native cosmology is closer to the truth than Western science—at least until Einstein’s discoveries of a hundred years ago—and always has been. For them, there is no such thing as past, present, and future lined up in a neatly unfolding line. Rather, time is understood as intuitively perceptual, unfolding in a continuous loop spiraling in all directions, without beginning or end.

On the introductory wall text for Everywhen, a quote from Kiowa writer N. Scott Momaday explains, “People walk through time as they might walk through a canyon, and one can pause and stand in time… one can take hold of it.” This notion of time happening all in one instant, infinitely, taps into our core as creative and spiritual beings.

Cara Romero’s photograph, TV Indians, is a good example of “everywhen.” The picture’s sepia tones are reminiscent of Edward S. Curtis, whose photographs established a popular image of indigenous people in late-nineteenth-century white America. Here, four contemporary Puebloans pose against a dramatically moody sky and wind-swept plain. The Curtisian tendency to romanticize indigenous people and conflate them with “Nature” is contradicted by stacks of old television sets in the backdrop against which the subjects prop themselves. Many of the TV screens depict images of Hollywood “Indians.” Dustin Hoffman’s Little Big Man is there, along with the crying “Indian” (played by an older man of European ancestry) from an anti-littering campaign; Billy Jack, the half-Native, taciturn ex-Marine do-gooder; and Tonto, the Lone Ranger’s sidekick. Romero’s photographs in this exhibition move through time and inform us that, truly, the past is present and the future has already taken place.

Naomi stands alone, posed by Romero like a mannequin in an edgy pop diorama, surrounded by objects suited to an exhibition in a natural history museum—as if she and her way of life were merely archaeological artifacts.

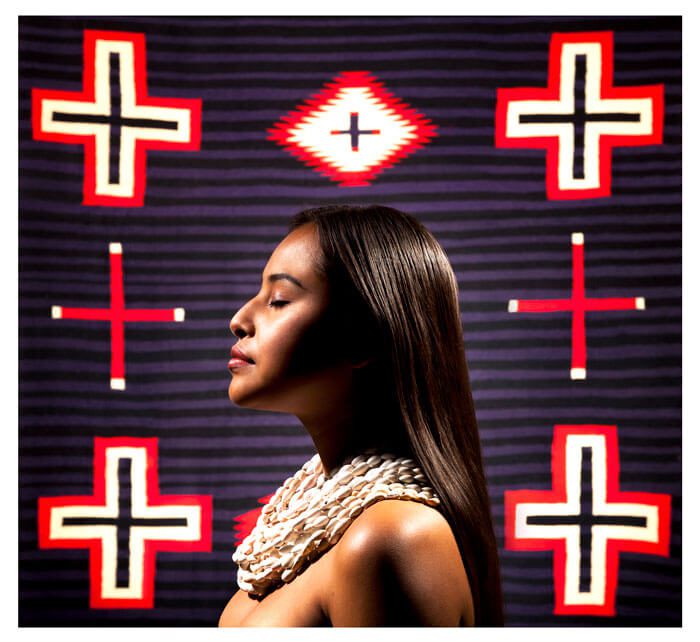

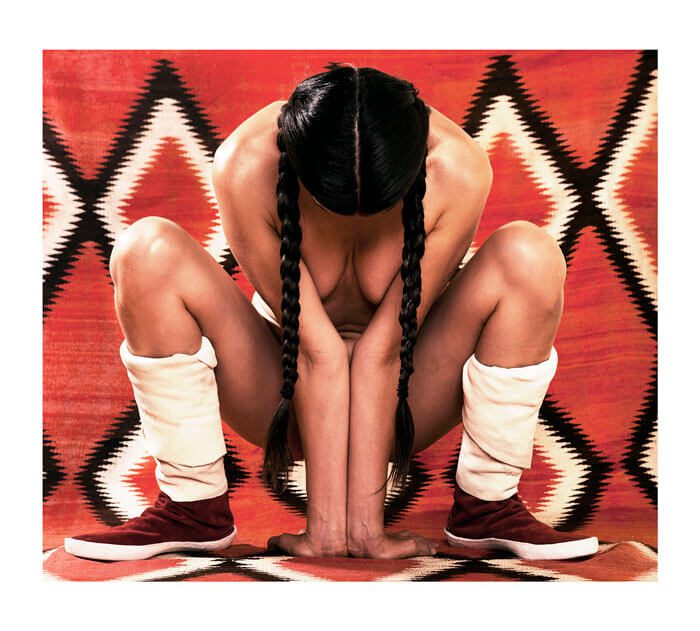

Romero was raised on the Chemehuevi Valley Indian reservation along the California shoreline of Havasu Lake in the Mojave Desert. She is married to ceramist Diego Romero, and the couple reside in his family’s Pueblo of Cochiti. These two biographical facts are necessary when digging into the meaning behind some of Romero’s iconography. For example, her portrait Naomi (2018) contains attributes of the Chumash people, a coastal tribe from Southern California. Naomi stands alone, posed by Romero like a mannequin in an edgy pop diorama, surrounded by objects suited to an exhibition in a natural history museum—as if she and her way of life were merely archaeological artifacts. Romero positions Naomi as a real live human being who is proud of, and very familiar with, her heritage. She explodes that “last of her race” stereotype into a fiercely contemporary, ass-kicking woman. Giving her a hot pink background and finishing the trim with black-and-white geometrics lends an edginess to the portrait. #YASSQUEEN is all that’s missing here.

Romero employs aspects of commercial and documentary photography with fantastical narratives to cut through notions of past, present, and future. In her photos, she creates her own realities and deliberately imposes them upon the viewer. Her image, Julia (2018), depicts a Pueblo woman with her relevant attributes, including baskets, a drum, and a chile ristra; yet, like in Naomi, she seamlessly crosses linear boundaries of time.