Investors are finally redeveloping Evans School—a historic schoolhouse in Denver’s Golden Triangle District—and displacing nearly sixty artists from their low-cost studios in the process.

DENVER, CO—It’s the outcome few wanted, but everyone expected: artists are finally losing their leases in Denver’s beloved Evans School. This blow for the neighborhood and the city’s arts and culture community hit hard after efforts by creatives to purchase the structure fell short earlier this year.

The building is undergoing mixed-use retail development, which displaces several dozen tenants—including nonprofits, pop-up galleries, and small businesses—from the heart of Denver. Yet this fate is neither unforeseen nor wholly unwelcome. Even as artists mourn the end of a landmark period in the city’s creative history, most are eager to decipher what’s next.

Evans School is a 1904 Classical and Colonial Revival-style schoolhouse in the Golden Triangle Creative District. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 and named as a Denver Local Landmark in 2001, the building was designed by architect David W. Dryden and named for Colorado Territory’s controversial (and genocidal) second governor, John Evans. The red-bricked edifice served as a primary school before falling vacant in the 1970s and now stands proximate to four museums, Civic Center Park, and the Colorado State Capitol.

City Street Investors, a development group that reworked and leases portions of Denver’s Union Station, purchased the unoccupied building in 2019 with Columbia Group LLLP.

What happened after was kismet for local artists. After hosting community “focus groups,” says City Street principal Pat McHenry, the COVID-19 pandemic and rising interest rates stalled redevelopment. Other sources suggest that strict zoning further derailed plans and developers were left with a gorgeous but empty structure—a financial drain, and a liability for neighbors.

The solution lay in a “marriage of convenience,” according to Adam Geluda Gildar, independent curator, artist, and Evans School tenant: interim artist studio spaces at subsidized rates. Renters gained otherwise inaccessible workrooms at around half or one-quarter of the market value while City Street and Columbia fended off losses during redesign. It was “a great way to get bodies in there and provide something for the community,” agrees McHenry. Even I shared studio space in Evans School from January to September 2023—an opportunity that afforded me my first ever studio experience and room to write.

Much of this marriage was officiated by Louise Martorano, RedLine Contemporary Art Center’s executive director, who collaborated tirelessly with Fred Glick of Columbia Group to subsidize workspaces and absorb liabilities through RedLine’s Satellite Studio Program. Glick had approached Martorano during the pandemic to identify and negotiate for artist spaces, and what started as a non-binding agreement for one three-month lease turned into fifty-two leases within nine months. “It was a wonderful situation that we found ourselves in,” says Martorano.

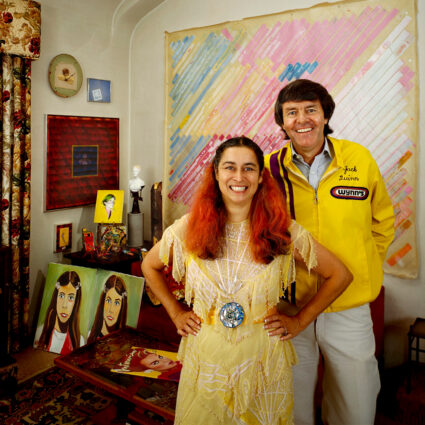

Adding to the magnetism of low-cost studios was the historic schoolhouse itself, with high ceilings, wood floors, and light in abundance. This gave artists enough reason to move in, though their leases were “clearly temporary” and sometimes month-to-month, says Geluda Gildar. “There’s a power to the space on its own,” he says. “And space makes real the practice [of art].”

Despite contracts that reserved rights to as little as five days’ eviction notice, Martorano estimates that well over fifty creatives have worked at Evans School in the three and a half years since the building joined the Satellite Studio Program.

Work—and play—they did. Sarah Darlene, a fiber artist, painter, grant writer, and yoga teacher whose two-year studio rental ended in October, reflected on the energetic, collaborative, and therapeutic collectives built within Evans School’s walls. “Art is medicine,” she says. “And if art is a healing practice, then what does that make spaces like these?”

Sharifa Lafon, Denver Digerati’s executive director and curator, similarly notes a post-pandemic energy as Evans School filled “an area of need in our community” for collaboration, creative energy, and joy.

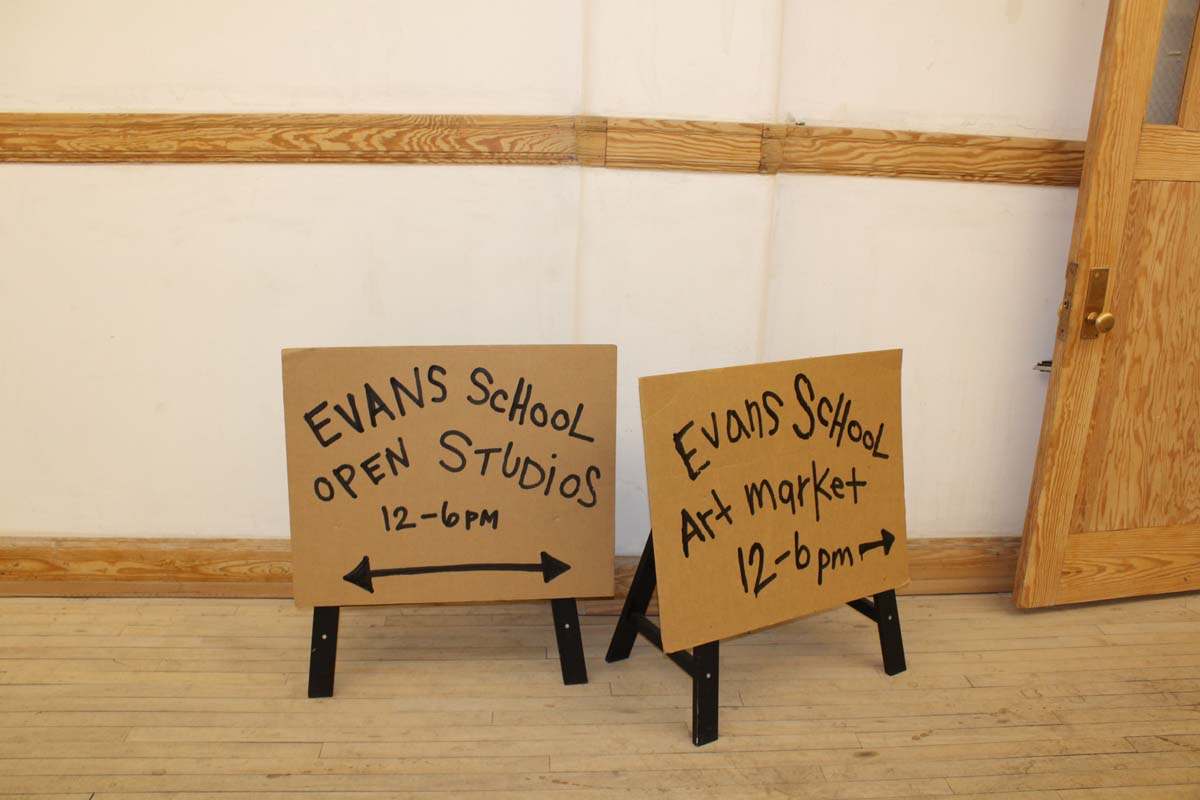

Artists and nonprofits like Denver Digerati have hosted myriad gatherings in the historic schoolhouse, including exhibitions, tours, and open studios—once welcoming over 400 visitors and earning $12,000 at an April 2024 art market. Other events embraced artists and locals alike: critiques, studio tours, performance art happenings, fashion shows, karaoke, dance and yoga classes, DJ sets, residencies, readings, digital projections, and more rooted Evans School to the neighborhood.

But since tenants knew that their charmed blend of below-market rent and above-average architecture would not last forever, their ad hoc tenant meetings turned towards organizing. “As we were doing all these markets, and as we started having all of these conversations… it became clear to me that there was a short window of time to scrounge up enough money to buy the building,” says Darlene. She sat down with Martorano in February 2024, who, with estimated costs from Glick, helped calculate an approximate $25 million-dollar price tag.

A loose artist collective brought their knowledge and connections (as well as differing needs and strategies) to bear researching grants, soliciting advice, developing a clear mission, or parsing the numbers. What followed was a brief but promising period; combined efforts through grants, foundations, public trusts, crowdfunds, markets, and nonprofits like Urban Land Conservancy made a purchase feel possible. Even the community seemed on board, with letters and emails addressed to artists from neighboring businesses and even from a former teacher who had worked at Evans School decades prior.

But with the last Open Studios and Art Market event on September 29, 2024, it felt like the dream had died for good. City Street and Columbia Group were moving forward with a mixed-use, public retail space called “Schoolyard” after the Denver City Council approved the Evans School Urban Redevelopment Plan on July 22, 2024. In that meeting, the Denver City Council approved a proposal from the Denver Urban Renewal Authority to pledge $26 million towards redeveloping Evans School. Funds for this commitment will come from tax incremental financing from sales tax and surrounding property taxes.

Though there’s no official move-out date, construction has begun on a beer/wine garden, coffee shop, and an auditorium-turned-event hall, with high-end offices marketed towards wellness groups and others upstairs.

The branding on City Street’s current website for Evans School claims that history “finds new life in the Golden Triangle as a creative work space.” But this seems at odds with investors’ priorities. City Street will still welcome artist studios, says McHenry, with at least one subsidized workroom allocated to RedLine. But as anecdotal evidence from artists, nonprofit executives, and even a Denver City Councilmember suggests, few—if any—can afford these rates or “buddy up” (McHenry’s words) to cover rent. And dozens of other artists will no longer have a place in Denver’s nucleus.

Lafon and others find it a challenge to determine what’s next. Denver Digerati hosted an artist residency at Evans School for the last two years and, in a tough economic climate, Lafon asks: “Is it more of a benefit to the community if I pay rent on a space that is giving artists space? Or if I take that money and pay an artist to do something?”

As for the core collective, Geluda Gildar says that they are “in negotiations” over new studios, while Darlene has heard of potential rentals on Grant and Lincoln Streets, East Colfax Avenue, and in Aurora, Colorado, though she will retreat to her house for now.

Yet Darlene, Geluda Gildar, Lafon, and others aren’t exactly discouraged. “These were two years that were a gift to my organization,” Lafon acknowledges, a sentiment echoed by many others in Evans School’s halls. Martorano feels similarly: Evans School “modeled what is possible in the midst of crisis.” And Darlene takes this sentiment further and believes that the artists’ purchasing quest was ultimately for the good: “I knew it was important to do, even if we failed. I really don’t consider any of it a failure because I think it sparked a lot of conversation.”

It’s difficult to see this new chapter for Evans School as anything but a complicated loss for the city, though, now seeing what might have been. “One of the great things about [Evans School] is that it was big enough for fifty of us [artists] to be here, and that is really rare,” says Darlene.

Denver may never see a generative space quite this big—or this central—for a long time, unless other developers “might employ a similar model for short periods of time,” as Lafon suggests. While many came into Evans School determined to make the most of a short stay, there’s no denying that we may have just witnessed a brief but glorious chapter in Denver’s history. But it also begs the question: if artists can do so much with so little, what could they do with more?