East of West, Santa Fe

Inaugural Exhibition

December 15, 2017 – February 18, 2018

How much value do we put in the terms “east” and “west”? I think, for instance, that, when Columbus blundered his way to the Americas, he believed he had gone so far west that he was indeed east, a notion he was committed to until his death. Even if his logic was ultimately bunk, it still marshaled the modern era of geographical thinking, with colonialism soon shaping both mental and actual maps of the world, as well as the fictions of otherness that accompanied discovery. The West, then, is both the creator and inheritor of Orientalism, a tendency to depict those from the so-called Orient in the image of a projection, a fetish even.

This came to mind when I went to East of West, a gallery located on a quiet industrial cul-de-sac off Fox Road. The space opened in December with the mission of exhibiting contemporary art from a sweeping geography—the Middle East, South Asia, Africa, and their diasporas. The former warehouse had the air of being a work in progress: the second floor still needed some attention, but L.E. Brown, East of West’s founder, was determined to drywall the first floor’s exposed wood framing in time for a late 2017 unveiling. On view was a mix of photography, a two-channel projection, mixed-media works, painting, and graphic design made by artists from at least five different countries.

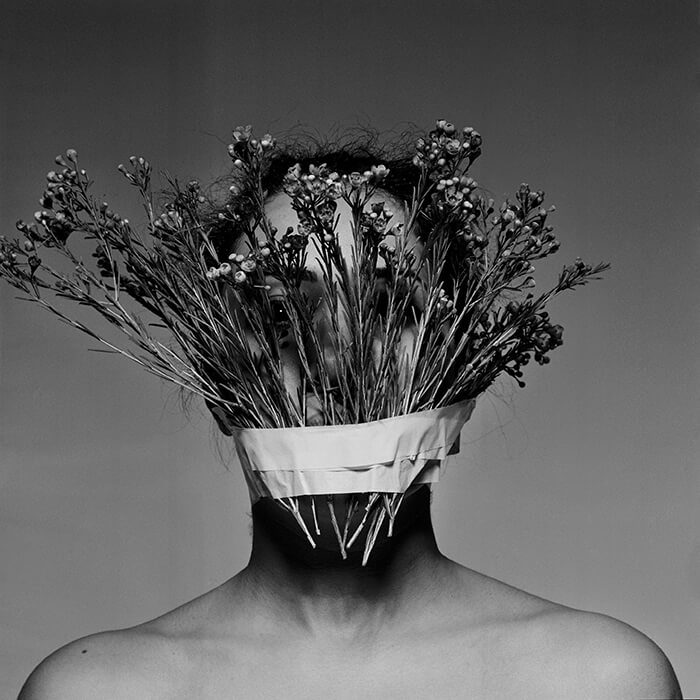

The mostly black-and-white photographs by Maha Alasakar, an artist based in Kuwait, dominated the space. With sixteen works from three series, her voice was consistently present throughout. In the series Undisclosed, various self-portraits gave no more than a hint of the artist’s appearance. In one, leaves of cabbage covered her face, and in another, the disguise came in the form of dried flowers taped around her head, a beautiful and menacing gesture. Alasakar’s series, Belonging, similarly blocked her face from view, whether with light, actual facades, or overlaid transparencies. Each was like a screen limiting viewers’ ability to come to any conclusion about her appearance or identity.

There was a loose dialogue between Alasakar’s photography and Saudi Arabian painter Nasreen Shaikh Jamal al Lail’s series titled Abstract, where black dabs of paint made seeing the artist’s face in totality impossible. The subject of the series is making the Hajj, the holy Islamic pilgrimage. In her words, “The black dots covering my face represent impurity, a lack of clarity, and distress. As the pilgrimage progresses, these dots are quarterly removed, leaving the face to emerge from behind the original opaque image.” In the final image, script spelling out the artist’s entire surname was overlaid onto the artist’s self-portrait.

In Younes Zemmouri’s digital prints, Arabic calligraphy from an Algerian dialect appeared to curve through the crooks of various classical and neo-classical sculptures’ bodies. The Rape of Persephone, David, and Venus de Milo were only a few of the objects of Younes’s intervention, the script appearing to support the weight of individual nude bodies. Yet this was an illusion, a strange visual juxtaposition of East and West and the various shades of shame that arise out of those places of cultural friction and xenophobia.

As its mission states, the gallery aims “to bridge the prevalent and growing divide between America and ‘othered’ communities, whose involvement in the arts is infinitely diverse yet often portrayed as a monolithic stereotype.” With surfaces, veils, illusions, scripts (and language barriers), limited views, and suggestions of infinity, I didn’t so much see the artwork as a bridge, though that isn’t to say it’s not. For me, I was most interested in the artists’ process of self-representation and the potency each had in both revealing and concealing. It was as if I were “peeking through a latticed screen,” not as a voyeur so much, but one not quite allowed the whole picture. This is how Madiha Siraj’s work, mixed-media renditions of Islamic patterning and geometry, is described on East of West’s website, but it’s fitting for the entire show.

I continue to wonder what it means to exhibit contemporary art from a huge swath of the Islamic world, especially after the realities of a sweeping travel ban. Now more than ever, art is a proxy, crossing borders where citizens from eight countries, six of which are primarily Muslim, cannot. When I asked Brown about the ethics of exhibiting the work of cultures that were not her own, she described her role as primarily a listener, an advocate, and a supporter. “It’s an important time for contemporary art that’s not [strictly] American or Eurocentric,” she averred. I sense that East of West is still finding its voice in Santa Fe, but I see that it’s nonetheless engaging timely questions about the role of displaying visual art from the East in the West. Indeed, as the stable of artists continues to grow, the statements, whether elusive or straightforward, would only ring stronger.