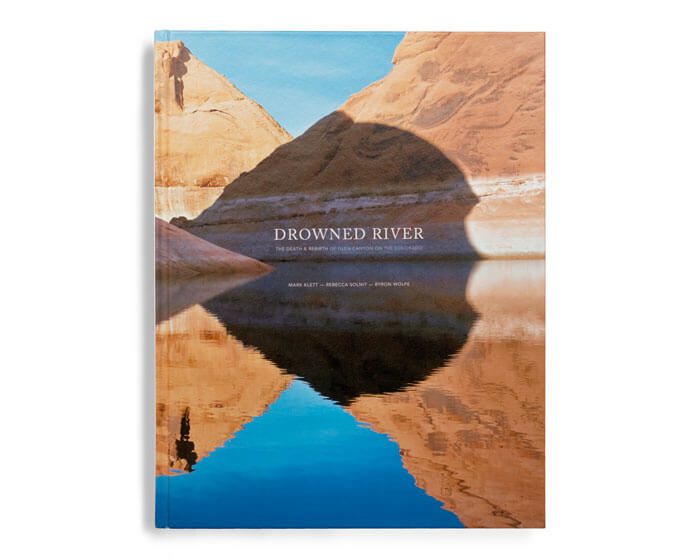

Rebecca Solnit’s writing on the intersection of environmental damage and the human body has long captured my attention as a reader and as an inhabitant of this planet. I spoke with Solnit and one of her collaborators, photographer Mark Klett, about their recent book, Drowned River: The Death and Rebirth of Glen Canyon on the Colorado (Radius Books), which uses photography and essay to document the current semi-underwater state of Glen Canyon and its precarious future.

Jenn Shapland: In the book, you describe the dam and many other projects in the West in terms of “overconfidence,” the developer’s belief that the climate itself is sustainable, that we will not and have not altered it. What is an alternate way of approaching the land of the West and an unstable climate that does not bely overconfidence? How do we live with “climate chaos?”

Rebecca Solnit: The opposite of overconfidence is humility—which, for environmental planning, could mean assuming first that nature is an order which we run the risk of turning into chaos when we mess with it, and a complex thing we may not understand completely. And as it turns out, we didn’t understand, since climate change was coming, and overdevelopment, and the assumptions about available water were based on exceptionally wet years. It also means listening to all concerned parties, which would’ve meant the native people and locals who opposed the dam and the environmental arguments against it (when they were against it; my essay in the book documents the various twists and turns of the Sierra Club’s position on the dam). Those engineers and politicians thought of nature as a chaos we gave our own new order to or a raw material, obedient, passive, malleable, we sculpted to our desires.

What made you want to revisit Glen Canyon, to write about it, and to photograph it? What did the place mean to you before you started?

RS: Mark and Byron [Wolfe] were invited to launch a project re-photographing Eliot Porter’s landmark book on the place [The Place No One Knew: Glen Canyon on the Colorado], and they’re the best collaborators imaginable—and camping in the Southwest was involved, so how could I say no? Also, I’d written before about Porter’s work, about the battles over the Colorado River, and climate change, and this was a wonderful opportunity to continue thinking about those subjects together.

Mark Klett: The idea for this project was first pitched to us by Colin Westerbeck, who at the time was director of the California Museum of Photography at Riverside. He wanted us to engage in a collaboration similar to the one we pursued in Yosemite. And he found the funding to make our first field trip possible.

Tell me about the form of this book, as it compares with your other writing on the environment and its history (thinking of Savage Dreams, A Paradise Built in Hell). What is the impact, in your mind, of combining the color photos with the writing? Did you approach this topic differently than your other long-form environmental writing or with a different audience in mind?

RS: Well, I mentioned two collaborators, but it’s really three, because our publisher, David Chickey, took Byron and Mark’s pictures and my essay and found a way to sequence and pace them that I think is brilliant and as eloquent an act as editing and scoring a movie. He sometimes spun out a single line of text across multiple pages, found a way to put that text and the hundreds of magnificent pictures the guys produced into relation with each other, and gave a kind of dramatic pacing to the whole that is essential to what the book is and how it works. I had interesting tasks at hand, to make something that worked with the photographs and described our process of exploring Glen Canyon but also reflected on Porter’s achievement and the history of the place, the environmental movement, and our understanding of climate change. And, of course, this book had maps, because maps are everything—we reused Porter’s map and commissioned a new map by cartographer William McNulty that shows that the river is being reborn from the sludgy ruins of the shrinking lake.

What prompted the inclusion of archival materials from Eliot Porter’s book? How do you envision your writing and the photos to be in conversation with his work?

RS: That’s really more a question for Mark and Byron, but this book is in design and content

a response to that earlier book, one era talking to another.

MK: Westerbeck’s original concept was for us to look for what was left of the places that Eliot Porter photographed. So Porter’s book was the starting point of our project. From early on, we discussed creating a book about a book. As Rebecca says, one era talking to another. And since many people will not be familiar with Porter, we thought it was important to reproduce at least some of his original book as the basis for our response that followed.

The design of Porter’s book also led to the ways our photos and the text were placed in relation to each other, and I agree with Rebecca that David Chickey skillfully placed the combination into a sophisticated and more contemporary design. He became our fourth collaborator.

What is the role of nonfiction writing in this era (political era, climate era, literary era, artistic era—you choose)? How can/Why should the nonfiction writer keep writing?

RS: I think that the role we’ve always had—of telling stories that incorporate others’ stories and facts, to report and to reflect—has only intensified in this era of lies and media manipulation and confusion. Our work matters, and though it’s not necessarily journalism, it can do some of what journalism does: report the story. Nonfiction has both the possibility of telling important stories and rethinking how we tell stories, what stories we’ve been given and what have been suppressed or lost, and how to tell a story and how much that “how” is part of what the story is and does. We tell the stories that change the world, as we’ve seen in this era of #metoo, Black Lives Matter, and Standing Rock.

Perhaps there’s a way in fiction and poetry you’re telling “my story,” but in nonfiction you’re often working with “our story” and even “their story.” You’re adding to or revising the historical record, listening to other people’s stories and trying to re-present them clearly and honestly, and your work has a different kind of weight and responsibility than fiction. I have long felt that what we do in nonfiction is close to photography—which makes fiction akin to painting, creating anything in the blank space that held nothing. Like photography, we work with what is out there in the world, but we have enormous creative choice in what we look at and how we represent it, which is why it’s always been so natural to work with photographers.