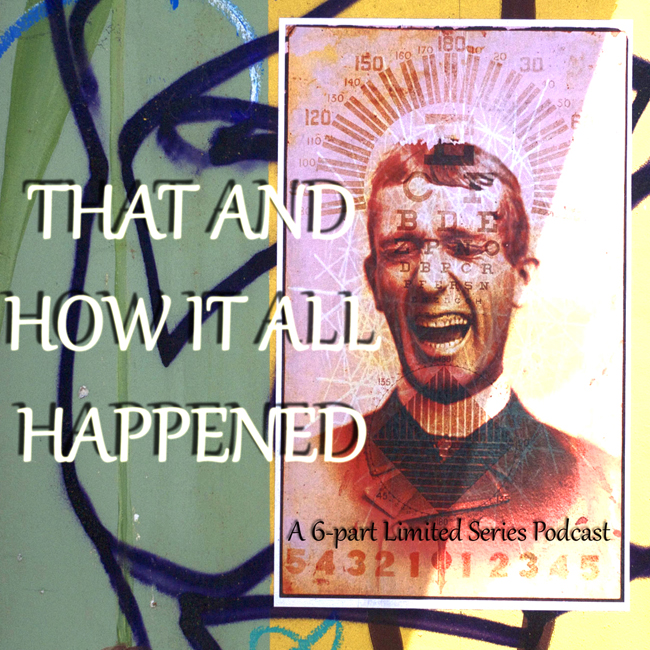

Pete Petrisko has spent decades participating in and documenting the downtown Phoenix arts scene, which has morphed from the grit of Metropophobobia and Gallery X to a place for brewpub-hopping.

PHOENIX—It’s the first Friday in October 2022, and I’m driving in circles through downtown Phoenix, looking for a parking space. First Fridays are a big deal down here, and every north-south street has been blocked to accommodate tents and tables and kiosks. I crane my neck as I pass Fourth Street for the dozenth time: what are they selling? Pizza? Paintings? Snow cones?

I’m here to revisit my past. Pete Petrisko has a retrospective show at a local gallery, and I want to see it. Just the thought of Petrisko having a thirty-five-year retrospective makes me feel old. How can that be? I wonder, as I turn onto Roosevelt Street for the twelfth time. Wasn’t it just a few years ago that we were all here, stepping over drunks to get into Gallery X, scouting out the latest issue of FLUKE at Metropophobobia, watching Rose Johnson paint herself blue while screaming poetry in the window of an empty storefront?

It was not. It’s been decades now since I was part of an audience for the local punk-adjacent DIY downtown art scene. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, we’d turn up for word-of-mouth performance art pieces in “the bad part of town.” We’d assemble at 1920s bungalows pretending to be art galleries for exhibitions we’d read about in hand-stapled, mimeographed zines. In an age before the whirring and pinging of devices that told us where everything was happening, we met and talked and relied on an underground that was ours.

What happened next was inevitable: we moved along. Oh, sure. Jeff Falk still makes and shows his art, though nowadays he’s more likely to do that in an esteemed eastside gallery than on a crumbling wall at the Ice House. Matthew Thompson still launches the occasional mail-art project; still publishes FLUKE now and then. Mike Miskowski still does art, though he’s morphed from performance pieces to political stuff, covering freeway overpasses with anti-GOP banners.

But Scorchydome is long gone. So are the Black and Tan and Punk Heaven and the Firehouse Gallery, the last of the live-work spaces that shuttered in 2016.

Only Pete Petrisko has remained. He’s gone on making art, championing fellow artists, gently correcting local media when we rewrite downtown art history. He makes prerecorded sound-art podcasts and soundscapes that he presents at local galleries and museums, and helms RPM Orchestra, a multimedia experimental band that plays behind silent films in local movie houses. And if he’s no longer running a brick-and-mortar gallery, if he’s traded writing art reviews in underground magazines for creating posts on social media platforms, he’s still doing what he’s always done: documenting downtown art as it’s happening, whether he likes how it’s happening or not.

I remind myself, as I continue scouting a parking spot, not to refer to Petrisko as a “founding father” of the downtown arts scene when I see him tonight. Don’t remind him that he’s “the godfather” of what’s going on down here, I think to myself, and for god’s sake, don’t call him an “overlord” of anything.

Petrisko’s not a sentimentalist, I know. He’s more engaged in recording history than in keeping the good old days from ending.

“I think of myself as a cultural worker,” Petrisko has told me. “The cultural part of it is the art I make, and the worker part of it is me saying artists should be getting paid.”

I want to ask him more about this, but it’s not going to happen tonight. I pull over onto Second Street and text Petrisko. I can’t find parking, I type. Sorry. I should have Ubered. I’ll see your show next week.

Petrisko was born in Chicago; his family moved to Glendale when he was a kid. Anxious to escape the suburbs, he headed to downtown Phoenix in 1987, settling at 11 East Ashland, a notorious scenester hangout with an art gallery on the ground floor.

“It was one of the first live-work spaces down there,” he recalls. “Before we even used that term.”

Petrisko made friends with people he’d read about in local zines: the painter Chris Winkler, who lived in a windowless room at the Ice House; artist and writer Rev. Nuclear; and Miskowski, a poet and furniture designer.

[11 East Ashland] was one of the first live-work spaces down there. Before we even used that term

“Those were crazy times,” Miskowski remembers. “Pete and I got invited to do a show in 1987 at the Armpit Gallery in Haight-Ashbury. The place was packed to see these two guys from Phoenix. Pete did his creepy clown act, and I read a poem and threw a box of paper scraps at the audience.”

I ask Miskowski if the young people who live in downtown Phoenix now want to have a box of paper scraps thrown on them, and he laughs.

“It’s all [Arizona State University] students down there now,” he says, not unkindly. “Trendy apartment high-rises. They have brew pubs. People go downtown to drink beer now. They want something different; I don’t know what.”

I phone Francine Ruley to ask her what we wanted from the downtown art scene, back then.

“We were looking for other creatures like ourselves,” she tells me. “I’d go to Hate House with my pink hair, wearing my shop-lifted Fiorucci, and see Pete and Miskowski. There’s be some guy wearing a Black Flag t-shirt, and I’d go, ‘That’s gonna be my next boyfriend!’”

Petrisko was the through-line, Francine says.

He gave us Gallery X, where you would see installation art and performance art and then you’d go out with everyone after and talk about what you saw.

“Then and now. He gave us Gallery X, where you would see installation art and performance art, and then you’d go out with everyone after and talk about what you saw.”

Francine doesn’t think that scene exists anymore. “But ask Pete,” she tells me. “We all left, but he stayed to watch and be supportive and, you know, be Pete.”

I do ask Pete. We’re sitting outside Lost Leaf, a pub and art gallery that’s hosting his retrospective show.

What, I want to know, is left of that old DIY vibe?

It depends, he says, on who you ask.

“Phoenix very much doesn’t want to talk about its art history,” he tells me. “The Arizona Republic has been saying for twenty years that ten years ago, they rolled up the sidewalks at 5 pm every night. You know that’s not true. There’s no institutional memory of what happened down here.”

Phoenix very much doesn’t want to talk about its art history… there’s no institutional memory of what happened down here.

But there’s your memory, I nudge Petrisko. You’ve kept that story alive, I say, especially when people claim that there was no art scene before the Roosevelt Row arts district of fifteen or so years ago. Why?

“I have to do it,” he says. “My head will explode otherwise. Over time my work here has changed. In the last fifteen years, I’m leaning more toward artivism and how it pertains to my community. I’ve worked behind the scenes with the Downtown Phoenix Arts Coalition on making live-work spaces legal down here. I’m doing more street art.”

Petrisko’s Shiny Happy People was one such project, a conceptual installation of wee statuary that was a memorial of sorts to artists who were migrating away from downtown.

“That was the real end of the scene you’re talking about,” Petrisko reminds me. “Artists were priced out of the neighborhood. They can’t afford to live here, or to rent a gallery here, or somebody put a sports arena where their art studio was.”

I want to say something about time marching on, but I’m afraid I’ll sound like someone’s grandmother. Instead, I ask Petrisko whether all those people clogging downtown streets are looking for their people, as we once did.

He doesn’t think so.

“The underground used to be like an onion you had to peel,” he tells me. “You didn’t know what you were going to find downtown in a gallery or on the street, and you didn’t know who would be there to see it. Today, you know what’s happening at which location and which of your friends is already there. Anything underground could be tomorrow’s buzz feed. And that’s not very underground.”

Some of that DIY spirit remains, Petrisko says. “There’s the Hive, which shows and sells art, and there’s Mural Alley.”

But many of the former downtown artists have moved their studios to Sunnyslope, or to one of many art spaces in downtown Mesa. Petrisko himself has relocated to an uptown neighborhood.

“I’m observing downtown from a distance, an artist who imports his art to downtown,” he says. “I’ll never stop observing downtown or commenting on it. It’s what I do. I’ve spent a good part of my life down there, and I still want to hang out with my people. Even if there are fewer of them down there anymore.”