Marfa Book Co, Marfa, TX

August 9 – September 1, 2017

En route from one Southwest arts oasis to another, determined to see the works of Doris Cross (1907-1994) in Marfa and carrying a friend’s artwork in our trunk, we passed through the heart of darkness that is the oil boomtown of west Texas and southern New Mexico. The landscape, usually marked only by occasional ranches, was remade by fracking sites and pipeline construction. If only, my partner said, Google maps had an option to bypass not just traffic and toll roads, but hellscapes. Erasure can often feel desired or necessary as we navigate the world we’ve damaged, and I wondered how this related to Cross’s artworks, which function by erasing, obscuring parts to isolate and connect others.

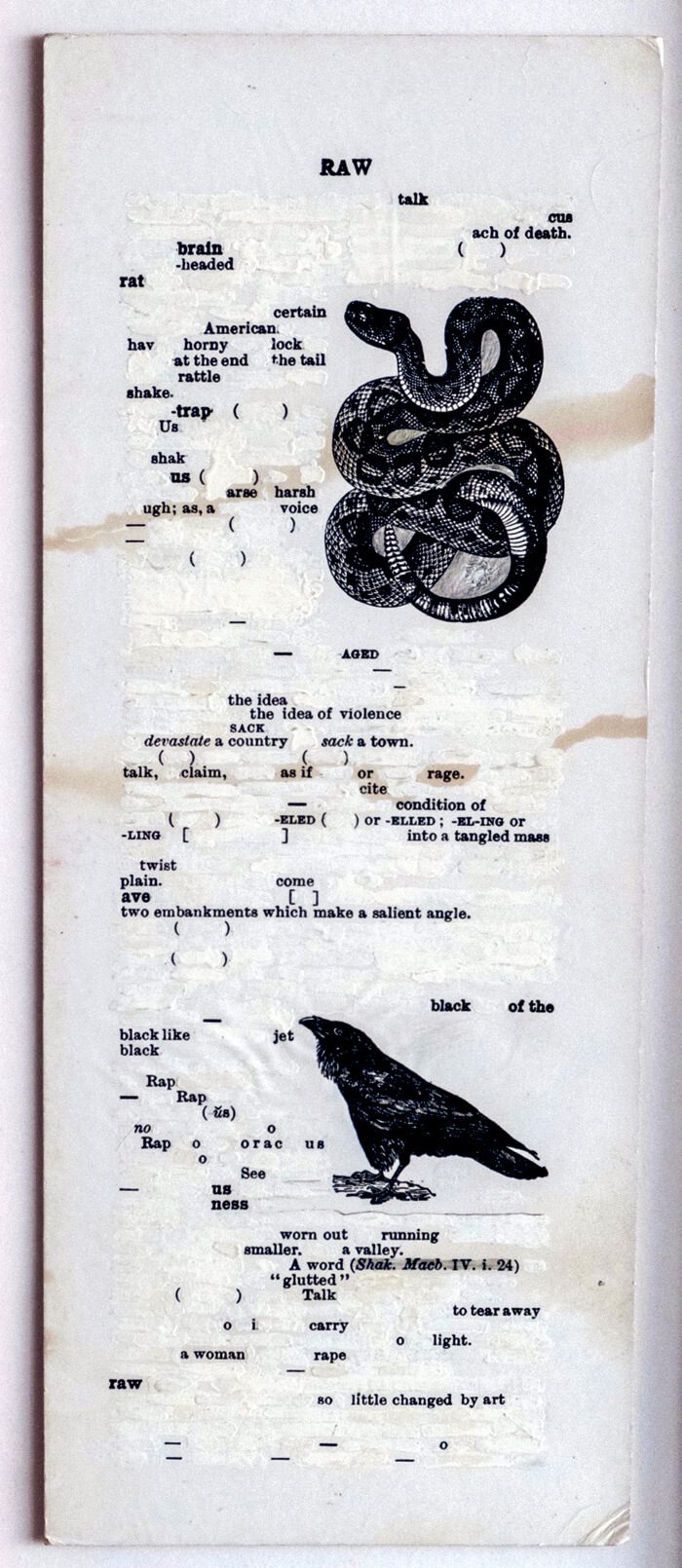

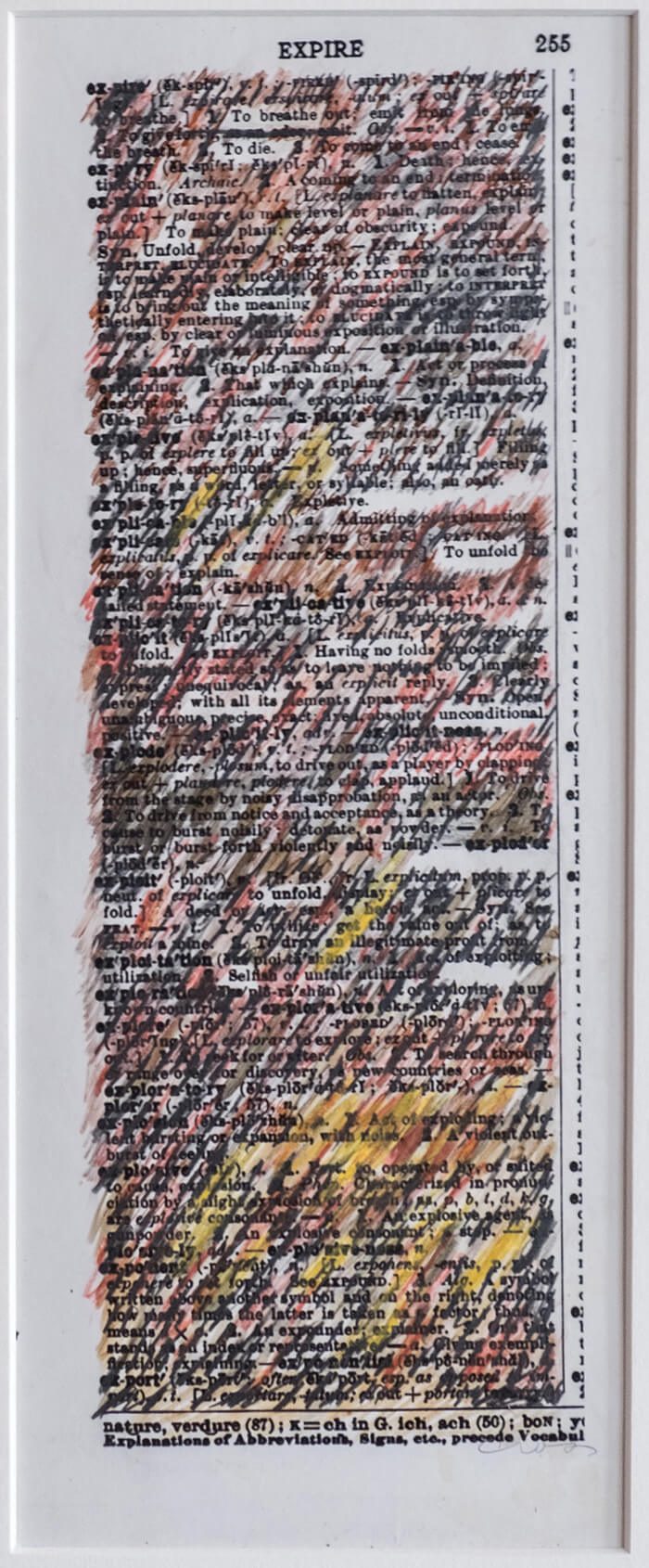

Doris Cross: Selected Works runs the length of Marfa Book Co.’s intriguing flat file collection, which contains the works of local artists. Each of the sixteen framed “reworks,” as Cross described them, is thrillingly unlike the rest of Marfa’s designscape. In the midst of all that is sleek, minimal, and Juddified (Hotel St. George, the new home of Marfa Book Co., included), Cross’s works are rough, layered, and messy looking (though not messy). Many of the pieces are markedly different from one another in production and effect, despite having been made using fifty pages of a single dictionary Cross had as a child. These select fifty pages of the 1913 edition of Webster’s Secondary School Dictionary constitute the material Cross reproduces, whites out, covers in masking tape, and colors over with paint, crayon, or pencil. She traffics in language and pauses, rather than shape and blankness.

If Cross’s resemble any other works on display in Marfa, I’d say they come closest to the John Chamberlain cars: twisted reshapings vertically perched, ballerina-esque in their delicacy given the cobbled-together nature of their assembly and raw materials.

If Cross’s resemble any other works on display in Marfa, I’d say they come closest to the John Chamberlain cars: twisted reshapings vertically perched, ballerina-esque in their delicacy given the cobbled-together nature of their assembly and raw materials. Her works merit continued looking and relooking, and I returned to the bookstore the next day to see them again in daylight. The works were on display as part of the first annual Marfa Poetry Festival, which included a small press book fair, readings by Texas poets, film screenings, and live music from Wednesday to Sunday, culminating in a reading by current Lannan Foundation resident Cathy Park Hong. At the end of the display, other notable examples of erasure poetry, including Jen Bervin’s Nets (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2004), Mary Ruefle’s A Little White Shadow (Wave Books, 2006), and Tom Phillips’s A Humument situate Cross in dialogue with poets who reuse and reshape hefty works: Shakespeare’s sonnets, a forgotten nineteenth-century text, and a Victorian novel, respectively. After reading what I could find about Cross—not much, though her work and life certainly deserve a book of their own—I considered how she would respond to being included in the poetry festival. She told one interviewer in 1981, “I’m not a poet, but I’m discovering something about poetry. Condensation creates—can create—an unbearable intensity.” Her works are also collages, a means, I find in curator MaLin Wilson-Powell’s notes on Cross, “through which the artist incorporates reality in a picture without imitating it.” Cross’s reworks assemble poems and images by, in Cross’s words, “leaving things—in this case, words, where they are found.”

With the shape of the dictionary column, which she described as a body or a figure, she draws attention to the headings and the resonances they create, using them as titles. Her columns put onto single words—like “odd,” “expire,” “puritanic,” or “anchor”—this “unbearable intensity,” demanding that the language of the dictionary come under scrutiny and present new meanings and associations for words in the very place we turn to for their definition and stabilization. She obscures or draws attention to the dictionary’s own images and illustrations, in one case framing an octopus, in another covering and incorporating it into her own design. The poems she finds in these columns are also bodily and body-smeared, sites of interiority, malleability, and self where one might seek objectivity and stable meaning. “Bodement. A prophecy A woman’s worn body wet earth black wood of trees the hills where tea is grown. A kind of black tea.” This seems to be part of Cross’s project, to call into question that stability through manipulation and materiality. My internal Wittgenstein cheers her on: meaning is use! Cross’s use redefines.

Cross began erasing in 1965, and she’s credited in some places as the first practitioner of erasure poetry. A painter by training, Cross studied at the Art Students League and the Pratt Institute and studied with abstract expressionist Hans Hofmann. She was the first woman artist to have a solo exhibition at the New Mexico Museum of Art during her lifetime. In 1991, at age eighty-four, she had a stroke and remained partially paralyzed and unable to speak for the rest of her life. There’s a pre-stroke interview with her online, and she’s impenetrable, unflappable, hilarious. “You tell me what I am,” she replies to a question about how she’d like to be thought of. Cross saw herself as an avant-garde artist, ready to be misunderstood. She was adamantly against personal history and the mythologization of the artist, but she was also trying to write her own version over the top of the narratives written for her.

Why erase? What is the power of erasure, removal in a cluttered world? New stillnesses and clarifying distillations.