-

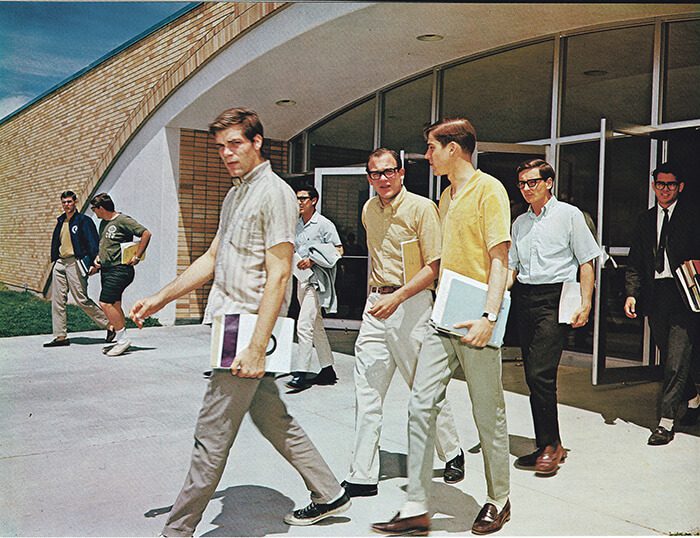

College of Santa Fe yearbook, 1967.

It was like déjà vu, or rather a bad dream that repeated exactly twice. First, it was the closure of the College of Santa Fe in 2009 and now this, the scheduled closure of Santa Fe University of Art and Design in May 2018. While CSF had made it past middle age, if you started counting from the moment of its accreditation in 1965, SFUAD, run by Laureate International Universities in the last eight years, hadn’t even made it into adolescence. By any standard, both institutions’ ends were premature. Now it’s time to look back, to assess, to take stock of a series of starts and stops that has not yet fully unfolded. In that way, it’s hard to make sense of something still in progress. It’s like trying to describe a dream before it’s even finished. Still, in speaking with many former students and faculty members, it has become clear that the stories, whether completed or in the making, and those who told them, were the most significant legacy of both institutions.

In this way, Reuben Greenwald’s words rang true: “The campus is the people who are there.” An alum of CSF, Reuben currently works as Associate Director of Student Engagement and Outreach at Sacramento State University. What he was getting at is the fact that people make a place. Built environments hold significance unto themselves, but what are they without those individuals and collectives whose interactions and conflicts give them life?

REMEMBERING THE LASALLIAN MISSION

If you ever want to hear the story of the College of Santa Fe’s genesis, Brother Donald Mouton, one of four thousand members of the Lasallian Christian brotherhood (founded by Jean-Baptiste de La Salle in the seventeenth century), is the person to ask. Many people I sat down with spoke very highly of his ability to teach and tell a story; they could still remember his courses by name even years after they left: “The Bible as Literature,” “Prophets as Poets,” and “Shakespeare and the Bible.” His courses all had a literary undercurrent, and all of them “were taught with verve,” as my dad, Richard, another alum of CSF, put it.

Originally from Lafayette, Louisiana, the heart of Cajun country, Brother Mouton began teaching at the College of Santa Fe in 1971, after receiving his doctorate in theology at the Catholic University of Paris. He was later president of the College, between 1982 and 1987, only to step down from his post to return to his original mission—and the mission of the brotherhood as a whole—teaching. Save for a six-year hiatus when he was on leave as a provincial superior in New Orleans, from 1990-1996, Brother Mouton taught continuously, first at CSF, then SFUAD, until the Spring of 2017. In the absence of the interim president, Maria Puzziferro, who was warned not to come to the May 2017 commencement in light of protests over her administration’s bungled handling of the school’s closure, Brother Mouton was given her role as Master of Ceremonies; he was already the Grand Marshall. By that time, he’d attended “at least forty different graduations.”

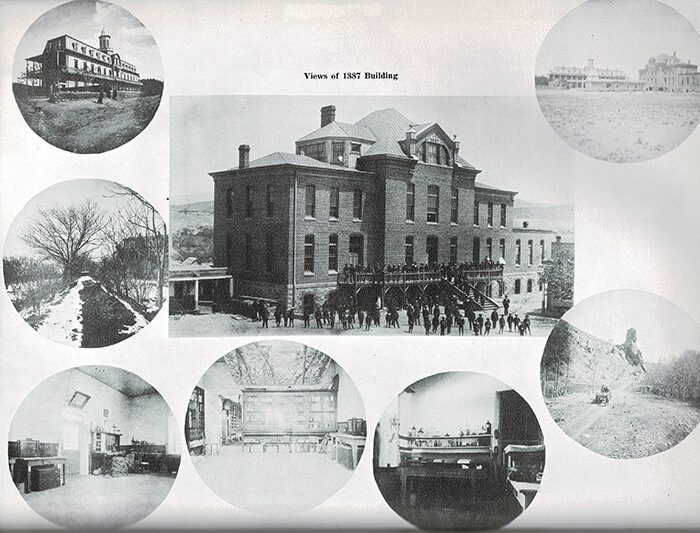

Over the course of an hour and a half, he narrated the institution’s beginnings in a distinct Cajun accent. As the story goes, four Lasallian brothers arrived in New Mexico in 1859 and, under Bishop Jean-Baptiste Lamy, began St. Michael’s College. Though it had the designation of college, it was only a primary and secondary school, located near the San Miguel Mission and on a thoroughfare that in time got the nickname College Street. Later, in 1874, and under the territorial government, the school was chartered as an institution of higher learning, the first of its kind in New Mexico. At that time, the College could give teaching diplomas to students, who then became teachers in their own northern New Mexico communities. Later, when New Mexico became a state, the school was incorporated, too. About 20 percent of the delegates to the statehood Constitutional Convention of 1910 were graduates of St. Michael’s College. The school continued to offer college-level courses until the end of World War I.

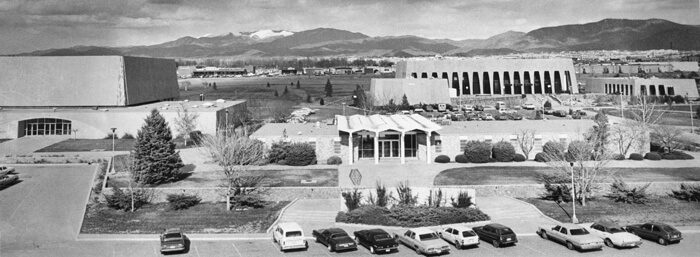

“All the tumbleweeds piled up in between the barracks buildings,” Brother Mouton said as he began detailing the more recent history of the school on the campus of the old Bruns Hospital, perhaps best known for treating the men—mostly New Mexican—of the 200th Coast Artillery Regiment, or those who were subject to the Bataan Death March. The hospital was an economic buoy to Santa Fe, but when WorldWar II ended, it promptly shut its makeshift campus down, leaving a host of temporary structures behind that were later cut up and hauled off by various federal and state agencies. Deserted for over a year as new plans were hatched, the hospital collected the errant tumbleweeds eddying between north and south. Older community members still remember the days of the Bruns Hospital. More recent graduates of CSF recall the ghosts the hospital left behind. Nurse Medina became a familiar name, a supposedly headless spectre who could be heard wheeling bodies around the barracks that were integrated as CSF facilities when Brother Benildus, then head of the old St. Michael’s College, acquired almost half of the properties in 1947. In September of that year, St. Michael’s College opened its doors on the location where it remains today. Then, it was at the edge of the city. Now, it’s dead center. Twenty-three men graduated in the first class of 1953.

The height of enrollment was in the late 1960s, according to Brother Mouton, a time when the institution was renamed the College of Santa Fe (and earned its accreditation) and when women were officially admitted. In those years, the Academy Award–winning actress, Greer Garson, and her Texas oilman husband, Buddy Fogelson, became financially involved with the College, eventually underwriting the construction of a 514-seat theater on campus, Garson Theater, and later Fogelson Library, which now houses almost 300,000 books, including rare books and a collection of mid-century (Jens Risom) furniture. Garson even performed in the student production of The Madwoman of Chaillot and was present in other ways as well. When Cheryl Odom moved from Los Angeles to Santa Fe in 1980 to teach costume design, the actress left a personal note of encouragement, written on her and her husband’s characteristic Lightning Fork Ranch stationery, with a bouquet of flowers.

Since its construction, the theater has housed many standing-room-only shows, such as Hair, and was the site of drag shows and a wildly successful annual haunted house, both to fund student scholarships; its second story catwalk was, moreover, notorious for laser tag competitions and beer hangouts. One of the most memorable pranks took place there when, one winter night, an inflatable Santa Claus from the parking lot of the Toyota dealership across St. Michaels Drive ended up atop its roof. To this day, Garson theater remains beloved, a fact that’s obvious in the local efforts to preserve it after Laureate International closes its doors in the spring. A local petition, spearheaded by alumni and faculty on change.org, requested that the theater remain open and accessible to the public. “We, the alumni, along with community members, voice our request that the venue be preserved and available for future use, as we see immense potential for the campus and theatre community.”

With declining enrollment since the 1970s and ’80s, CSF had “been struggling upstream” for some time. Even so, after the closure of the University of Albuquerque in 1986, the College opened upan evening and weekend program in Albuquerque, under Brother Mouton’s tenure, catering to nontraditional students from Sandia Laboratory and Kirtland Airforce Base. When CSF closed, Louis University in Chicago took over the program, which is still running today.

The real demise came with a number of “construction ventures,” including the THAW visual art center, the Shellaberger Tennis Center, the Mouton Student Services Center, and renovations to Benildus Hall. The “expense to increase the enrollment ultimately strangled the college financially,” Mouton told me. Like many other universities looking to expand in the 2000s, CSF had come to an interest rate swap agreement. In 2009 alone, CSF was one of twelve small private universities or colleges that closed amidst the fallout of the broader 2008 financial crisis. Thirty-eight million dollars of bond debt, a majority of it refinanced in 2006, was owed to the Royal Bank of Canada when the school finally threw in the towel. The extent of the debt had not been disclosed under the presidencies of Linda Hanson, Mark Lombardi, and Stuart Kirk, leading to a number of fiscal misconduct and misrepresentation lawsuits from faculty members.

“A lot of lifeblood was given by the brothers,” and even as the school incorporated more lay faculty and administrators as time went on, the original mission remained the same: academic excellence. The school was Catholic, but it nonetheless “honored others’ religious traditions,” celebrating non-Catholic holidays (Seder, for example) and keeping the Lasallian passion for teaching and learning alive throughout. The school cultivated “the whole person.” There was little bureaucracy and “not a lot of red tape,” one person also recalled, signalling a sort of freedom in the student body that’s telling of liberal arts institutions. At one point, a student of CSF even took his own band on a recruitment tour for the College. Others spoke of Quadstock, an event for student musicians to gather in the public outdoor area of the Quad. Ben Haggerty, now known as the rapper Macklemore, was once a participant back in 2002 when he was a student at CSF.

Former students now work at the Santa Fe Opera, as state representatives, in design firms, banks, artist collectives, publications, museums, in marketing, education and prevention, and other key non-profits. They have transformed the fabric of their respective communities and continue to do so.

“We cannot erase the fact that the footprints are still there,” Brother Mouton reflected as our conversation came to a close. To him, the students hadn’t changed much over the years in their capacity to learn. His classes, even recently, always filled up. Yet for all the personal memories that animated the place, it was also evident that institutional memory was less reliable after CSF transformed, for lack of a better word, into SFUAD; the footprints, although clear to some, went unacknowledged by Laureate in the transactional process. In fact, Laureate had never operated a residential campus before, and the corporate mentality of a for-profit only added to a kind of strategic forgetting of its predecessor’s most significant assets, its people. And while CSF thrived in part because of its alumni, Laureate absorbed the long lineage of the College’s high reputation into its own very new origin story without striving to create links with past students near and far. It was a moveon Laureate’s part that left many CSF alumni bitter but that nonetheless fostered new communities on social media, dedicated to staying in contact with one another. As Julie Bernard, another CSF alum and former Director of Alumni Affairs (2006-2009), pointed out, the college created a unique environment where students of all stripes could thrive, many of whom continue to make a difference whether in Santa Fe or elsewhere after graduation. “CSF has become an asset [in the city] because of the people—teachers, legislators, artists, and gallerists,” who’ve come out of its programs. Former students now work at the Santa Fe Opera, as state representatives, in design firms, banks, artist collectives, publications, museums, in marketing, education and prevention, and other key non-profits. They have transformed the fabric of their respective communities and continue to do so.

-

Greer Garson, 1971, College of Santa Fe yearbook.

PROJECT WORK

When Linda Swanson, Dean of the School of Visual and Communication Arts, addressed SFUAD’s graduating class of 2017, her speech lingered on the experimental aspects of laboring under the Laureate umbrella. She had been teaching on the same campus for nearly forty years, witnessing the changeover from one institution to another. After CSF closed, Laureate had regrouped, capitalizing on an arts foundation laid by its predecessor in the 1980s with the hiring of Richard Cook and the creation of an art department and a thriving film department. SFUAD was part of that legacy, though it operated much on its own terms. Or, to say it differently, SFUAD was a “project,” complex in form, collaborative in nature, though ultimately finite in shape. In Linda’s words:

To this graduating class, you are all artists, and you know your way around a project. It starts from nothing and initiates planning and dreaming, organizing and making. It demands intense focus, full-on commitment, research, creative problem-solving, negotiation, collaboration, reflection, soul-searching, harsh evaluation, determination, adjustment, and community. And that is what we did. We—every fully-present faculty colleague, each multi-tasking over-worked staff member, and all, all of the students, all of you—because this kind of work, “project” work, not institutional work—blurs hierarchies and morphs roles. Together we invented, challenged, rewrote, re-imagined… Because SFUAD was a new endeavor, there was no institutional current to float us along, so we made our own current—with frantic splashing, in-tempo kicking, and sometimes even graceful strokes. Faculty, staff, and students all pressed ourselves into action—physically, intellectually, and emotionally—and let the moments of thrilling satisfaction fuel the next round of challenges and adjustments.

What she best captured was that although debt and decline were and remain a harsh reality, with even harsher repercussions, those features did not define the institution’s community, nor the work on the ground that mobilized almost everyone. Since the days when the old army barracks were first inhabited by students, brothers, and later lay administrators and faculty, the campus had met challenges. Indeed, as Linda looked backward to look forward, so too have others, recalling how challenge and transformation were two sides of the same coin. In this, there was a pronounced sense that SFUAD marked a new era. Margaret Van Dyk, Director of Library Services, had visions of transforming Fogelson into “the Contemporary Art Research Center of the Southwest,” where, “We would complement the Georgia O’Keeffe Research Center, with its focus on modern art.” The hope was that the library would collect the work of its students. “I wanted our students to see the library as a living and amorphous resource that included them, that was utterly relevant to them.” In those experimental first years, there was also an exchange program with Laureate’s Mexico campuses. Some of those students later pursued fruitful careers in the U.S.

Though Laureate was flawed as a corporation (they fired tenured CSF faculty as well as made massive pay cuts), SFUAD and its graduates are still making an impact. This is due to their own creativity and motivation, as well as the doubled efforts of faculty members and mentors, new and old, who offered compelling courses that would enable viable arts careers in creative writing, graphic design, contemporary music, film, and the visual arts, to name only a few. Tom Miller, now the lead faculty member in the Art Department, listed a number of former students who are now operating galleries or holding other key roles in reputable arts institutions, running large-scale community events, changing the face of design, and working in the film industry. More recently, Final Cutz, a dark zombie comedy was being filmed on campus. It was written and directed by Liam Lockhart, chairman of the Film School, and produced by Claudio Ruben, with a crew of film students from SFUAD. Zombies seemed an apt metaphor for the campus, expired in one sense, but still living in another. Whether in the film school or beyond, the students have, in large part, contributed to Santa Fe’s current cultural profile, making what Linda Swanson called “project work” into life work.

A GROVE OF ASPEN TREES

When the deal fell through with the Singapore-based Raffles, another for-profit, everyone collectively turned their attention to the City Council, who have, since the spring, held the fate of the campus in their hands. They recently issued a statement, shortened here for brevity:

The City remains committed to preserving an educational focus at the core of the SFUAD property…. The strategies and partnerships we’ll explore moving forward have the potential to continue the education mission, while also driving job creation, supporting creative arts like film, addressing housing challenges, bringing the community together, and helping us fulfill our duty to protect the taxpayers’ investment in this land. We’re excited about what the future may hold.

Unsurprisingly, the statement is vague, making it an especially important time to remember the original mission of the campus, to serve the local community—Santa Fe and northern New Mexico. In this remembrance is a collective push to hold the City Council accountable to their word and to remain transparent in the process.

Another person spoke at the most recent graduation: Estevan Rael-Galvez, former state historian, and the only SFUAD board member in attendance that day. In his speech, he conjured the metaphor of an aspen grove and its immense root system. Aspen trees, he said, “emerge following a fire to the forest, a trauma perhaps metaphorically like the one SFUAD is moving through right now.” Now, we must await the next aspen grove.