“The planet seen from extremely close up is called the ground.” —Mary Ruefle

Landscape painting: the passé genre that dominates so much of the world’s understanding of Southwest art. For me, first it conjures images of Albert Bierstadt (wrought with a minefield of American colonialism), the sappy, wistful romance of a Caspar David Friedrich abyss, and the airy, observational paintings of Provence by Paul Cézanne, thanks to the technological innovation of premixed paint in a tube that allowed him to travel light and work outside. Given the rapidly changing, often deteriorating state of the planet today, traditional landscapes are almost automatically tinged with nostalgia. But some contemporary artists are working to undermine, change, and redirect ways the Southwest landscape is interpreted. I’ve found landscape to be a central, but not primary, component in a number of artists working today. This shared region has served not only to keep the landscape relevant, but also as a reminder of the land as an undeniable foundation to many projects. The West functions in multiple areas: as painting in the expanded field, as a social space, as body, and as quiet solitude in observational painting.

“I was undisturbed by humans, but maddened sometimes by fierce wind-driven dust, which would coat the fresh gobs of paint on my palette.”

—Rackstraw Downes

Painting en plein air has long been the cornerstone of the tradition of landscape painting in the Southwest. Since the 1930s, Georgia O’Keeffe’s enduring relationships to Cerro Pedernal and the geological layer cake of Abiquiú, New Mexico, have played a major role in defining the history of modernism. While many painters are still actively engaging the land through an observational technique, the decisions of “location” and their attached meaning vary wildly. Since the early ’90s, almost evenly west and due south of Santa Fe, some of the most important landscape paintings depict not notable features like Pedernal but nondescript locations in the Chihuahuan Desert. Rackstraw Downes has dedicated himself to the minutiae of unassuming and otherwise banal locations, such as refinery-town culverts and the now-eerie, untenanted floors of the World Trade Center. Banal, that is, until seen through the eyes of Downes. His approach to perspective features two devices: fisheye structures for a shallower depth of field and a sweeping, panoramic horizon line mapping the curvature of the earth for expansive vistas. His work is done, patiently, en plein air, fully exposed to weather conditions (in three-hour increments due to changing light from the active participation of the sun). This is not a bucolic, Japanese-inspired water garden in Giverny.

The deserts of the West, while sublime, are unforgiving, open expanses with few breaks from the strong, bitter winds and offer no cover from the severe sun. In short, it can be an extreme environment to choose to paint outdoors. Downes’s Presidio Horse Racing Association Track series, a set of four paintings along with studies and preparatory drawings developed between 2004 and 2007 and somewhere between the Chinati Mountains and Ojinaga, Mexico, demonstrate a clinical and sober approach to interpreting the land. Downes came of age as an artist during the height of minimalism, and I can’t help but consider how, directly or indirectly, it has informed his method of system-based image making. Like his titles, which use cardinal directions, the structured logic of his framing decisions of the landscape are as dry as variations of a cube. Looking West, North & Northeast: The South and North Horse Shelters, 2006, is at first glance an empty setting. Aside from the pink Chinati range, center-right in the deep distance which sets a boundary on the horizon, patches of dead brush punctuate an otherwise open field, with three skeletal shade structures of pipe and corrugated metal and a welded-pipe fence that runs parallel in front of sandy hills of little distinction. Why here? At this moment of questioning, the horizontality begins to form and become present. The painting is 15 by 120 inches, a uniquely wide sprint of a format, to be certain. The horizon line arcs across the center, and the manmade elements, all painted economically in white, float to the surface and suggest a grid in the lattice structure of pipe fencing. In the foreground, signs of human presence emerge on the surface of the desert floor in the carved marks of elliptical tire U-turn lines and footsteps that could only have made an impression after the rare occurrence of rain.

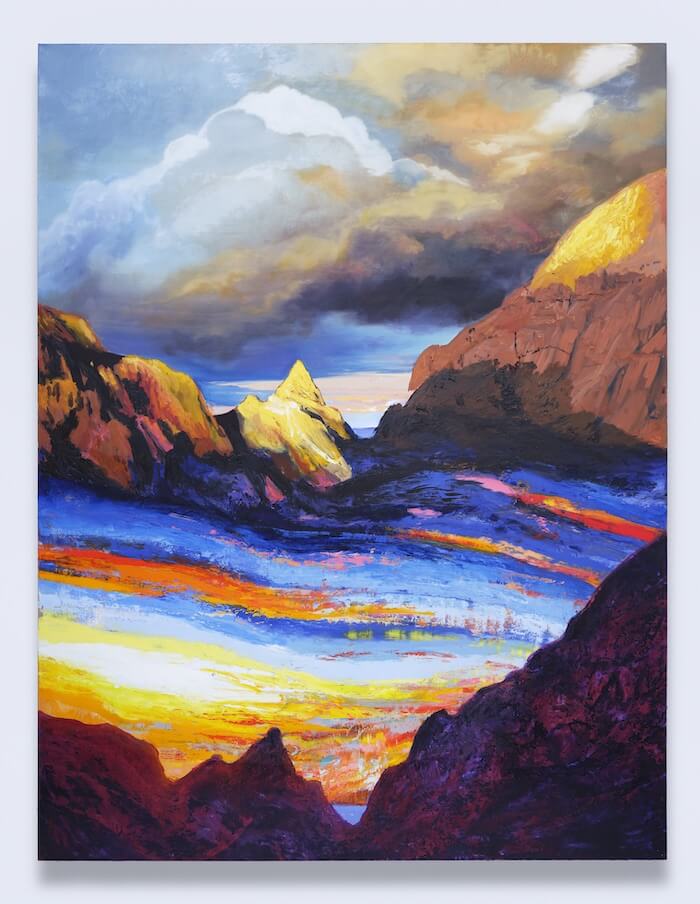

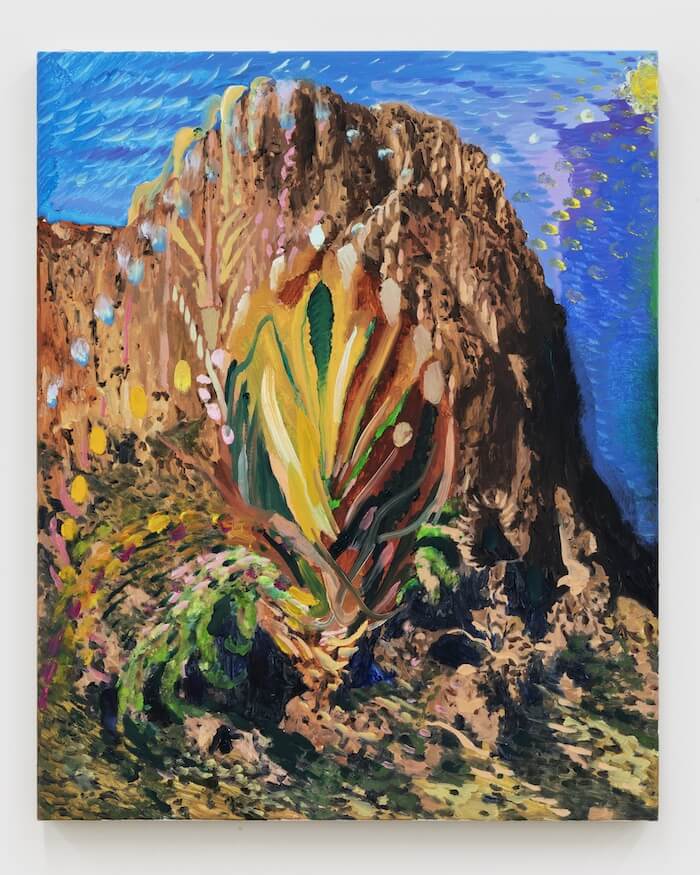

Van Hanos, a recent transplant to Marfa, Texas, is a deft paint handler who moves confidently through different modalities of image-making, ranging broadly from photo-based techniques to abstraction to plein air. I’m always amazed by his painterly invention of mirroring and inverting spaces—real and psychological. Hanos’s recent landscapes charge the genre with new life through layered meaning. That is to say, the paintings are as much about landscape as they are something else. Interior Landscape is a well-rendered painting of the Chisos Formation, with an overlay of radiant, agave-like forms materializing from the center as a spring. Vibrant mark making forms the sky in textured layers in a way that summons the spirit of early German Expressionism, à la Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and the Die Brücke group. Portrait of Our Mother as a Mountain is a striking double portrait of the Window Trail in Big Bend National Park, Texas, at sunrise and sunset. Hanos’s ability to collapse the passage of time into one image is both poetic and whip smart. There’s a phenomenology to experiencing the changing colors of a sunset or sunrise that Hanos captures in paint that recalls the framing of a Turrell sky space and the hypersensitivity of color in Monet’s Rouen Cathedral series.

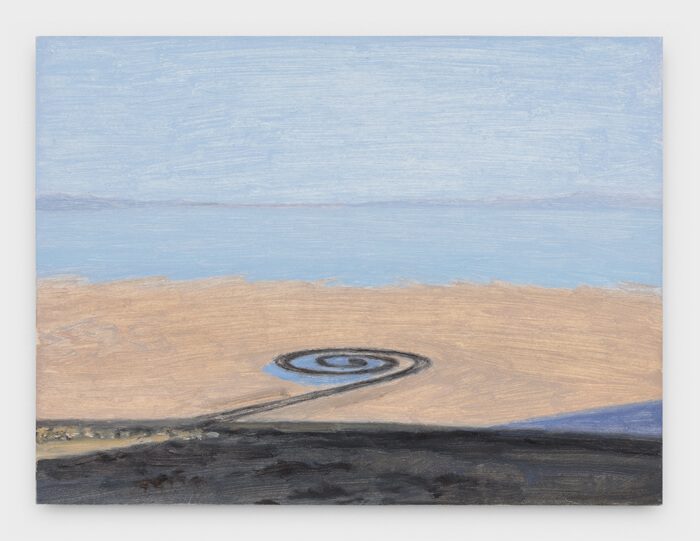

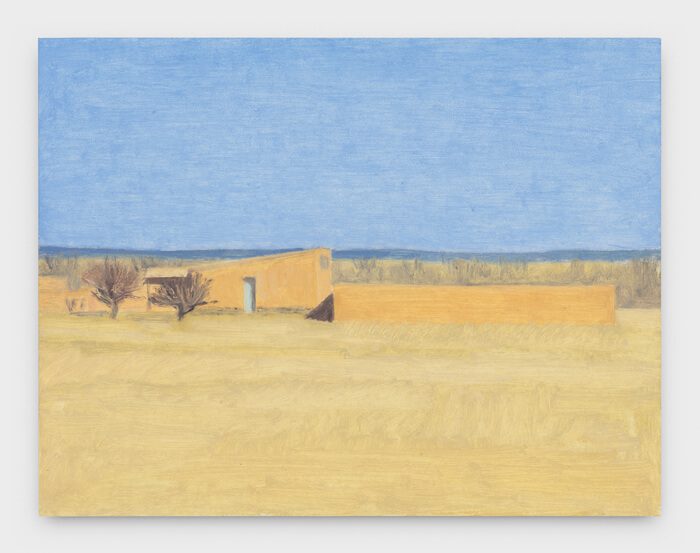

Eleanor Ray, based in Brooklyn and frequently in the Southwest, trained in observational painting at the New York Studio School. Ray, no longer tied to strict observation, chooses to work from memory and images sourced from her travel and time spent wandering around various sites. In an email exchange, Ray shared that “seeing in memory” is a way of opening up new compositions of past locations for her work. It comes across to me as an experiential painting practice of being in a space and knowing it by witnessing changing light and weather. This practice of observation never goes away, but the technical aspects of paint to canvas are kept in the studio. By and large, Ray’s body of work consists of vacant landscapes, inward-facing exteriors and outward-facing interiors balancing sun-bleached hues to create space for light as subject matter. Ray makes clear her Southwest interests through the sites she chooses and, in the case of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, paints again and again. In Galisteo (Agnes Martin), I couldn’t help but think of a private life made public—even after Martin’s death—only because Martin was so determined to live and work in solitude. That said, the painting is one of admiration for Martin, as it captures Martin’s sensibility of harmony through her home’s ability to blend into the landscape almost unnoticed. Ray renders the home’s architecture as solid geometric blocks laid horizontally, with shadow breaks from eastern sunlight marking it as a structure in an otherwise open field of tan, dry prairie grass. Only the right corner of the roof bisects the horizontal bands of brushwork that effectively define the gray cottonwoods along the Galisteo Creek and a wavering, dark blue line as a stand-in for the distant ridge that shapes the Galisteo Basin. The expansive presence of Ray’s thinly painted, pale blue, cloudless sky feels true to form and also operates as a nod to Martin’s serene palette.

“Rose-colored sand on the ridge maintains a perimeter between chaos below and an almost numerical perfection of blue sky, when in fact blue radiates down to me.”

—Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge

While these three painters continue to work with Southwest landscape painting in the most conventional sense, others seek to redefine what landscape can be to painting, using materials from daily life and new technological processes. Since the post-minimalism days of the early ’70s, pioneering feminist artist Harmony Hammond has continually questioned traditional supports in painting with unconventional materials and processes and an emphasis on the embedded gender and sexuality of her materials. In 1988, Hammond began teaching at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Her annual commute from Galisteo to Tucson and her time wandering the alleys of her Tucson neighborhood, Barrio Viejo, proved to be fruitful with an endless supply of abandoned materials to scavenge and form the body of work we now know as Farm Ghosts. Hammond has always been direct about her abstract paintings’ relationship to class structures, marginalized communities, and queer identity in rural America, and its gravitas is refreshing. Hammond’s Farm Ghosts series functions as a swan song to an agrarian life that has evaporated from most of rural America due to the rise of largescale commercial farming practices in the ’80s, brought on by Reagan-era pro-corporate policies. Stamped tin panels, rusted corrugated metal sheets, charred fencing, fragments of linoleum tile, water basins, and dilapidated rain gutters are some of the scavenged objects that would find their way into Hammond’s paintings. It’s important to note that Hammond does not see the Farm Ghosts series as landscapes, but of the landscape and informed by rural places.

The epic yet intimate Farm Ghosts: The Wife’s Tale (1991) consists of oil on found stamped tin, linoleum tile fragments, and canvas, along with attached metal buckets and adjacent water basin with cloth. The gridwork of oxidized stamped tin panels, likely used as a ceiling treatment in its previous state, has a russet hue similar to dried blood and is punctuated by scattered cadmium red gestures that read as fresh violence. The center panel consists of a visually striking, complex, broken grid formed by layers of found linoleum that calls to mind both quilts and Rauschenberg’s Bed. The reoccurring windmill in black weeps, floats in the frame, and casts a shade of melancholy over the tone of the painting. On Hammond’s windmills, Lucy Lippard writes, “Hammond has taken the figure-like windmill, made it fragile and vulnerable, standing alone in the void, a proxy for the farmer’s life and wife. She has seen it as a sun, and as a flower or a guardian of the landscape, as well as a symbolic “suicide tower,” referring to the rash of farmers who took their own lives when they lost their farms in the ’80s.” This heavy painting establishes a narrative of loss and labor. It acknowledges the labor of the wife, whose daily work both indoors and outside would otherwise go unnoticed. Also, Hammond suggests a vivid interior space for the narrative of the wife through materials with linoleum tile as flooring and stamped tin as ceiling. The text (CRY, LEAVES, LOAVES, GRASS) located across the center panel suggests interior labor and also pulls the narrative outside. Buckets hung across the painting and a water basin at the foot are objects of utility and call to mind tasks of carrying, cooking, washing.

For the past twenty years, a new mode of painting has pushed its way forward, without the need for paint, making use of Epson printers and ink. I affectionately refer to it as “CTRL P” painting, after the function keys used at the moment of production. Prominent visual artists making use of Epson printing for their paint practice that come to mind are Wade Guyton, with his coolly off-register monochromes, and Jeff Elrod’s frictionless drawing technique. In this camp, artist Peter Sutherland’s work is expansive in scope but mines images of the West (by proxy the highway), development/encroachment, and ski culture. The paintings in Forests and Fires from Sutherland’s 2016 solo exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis depict a dense, idyllic forest landscape, complete with a lush bed of ferns and a canopy so dense that sunlight barely enters. This almost-cliché of a forest scene is inkjet printed on perforated vinyl and adhered to OSB board with gel matte medium, creating a powerful effect of incongruity. Oriented strand board (OSB), used commonly in new construction projects, is composed of shredded wood fragments and bonded with a controversial adhesive containing formaldehyde. The perforated vinyl creates a double image of the forest and its hyper-processed, demolished self, complete with a vertically printed barcode that stands as a column with the trees. This double image is the crux of the work, as neither image pushes forward, but both stay unstable and at odds, while raising questions of development and deforestation.

Landscape in the twenty-first century is a quietly unflinching genre and can be found in some of the most unconventional forms of image making today. Rackstraw Downes teaches us a lesson in beauty found in unassuming sites, while Harmony Hammond builds a psychological landscape through meaning embedded in materials. Interestingly, the continual march of new technology questions painting at its core, with Sutherland’s use of Epson printers. The sober tragedy is that unlike past traditions of interpreting landscape in pristine beauty, contemporary themes reflect on the bleak outlook of an ecosystem exploited and destroyed by society. ×