Grand County commissioners in Moab took issue with a quote by a historic Black cowboy about racial and class equality in a mural proposed by artist Chip Thomas.

MOAB, UT—“I’m glad I fought as hard as I did to get that Charlie Glass mural up,” says Chip Thomas, alias Jetsonorama. He’s referring to the twelve-by-thirty-nine-foot photo of a Black cowboy he recently installed on the exterior of the Moab Area Travel Council building after months of fielding implicit and explicit pushback from Grand County officials who were hesitant to approve the mural on their property.

Thomas, a Black artist whose photographs and murals highlight people of color in the Southwest, had been commissioned by the city’s arts and special events department, Moab Arts, over a year ago to install two murals in town.

His first mural proposal, a happy-go-lucky image celebrating uranium mining in Moab, was approved without any trouble, says Melisa Morgan, assistant director of Moab Arts. His second proposal, an enlarged archival photo of Charlie Glass, a Black rancher and historic Moab character, coupled with a quote equating class equality with racial equality, caused months of feet-dragging on behalf of the county and was only approved, Morgan says, on the grounds that the quote was swapped for something less “depressing” and void of any mention of race.

“It was a fight to get it up on the wall at all,” says Thomas about the Charlie Glass mural. “Then there was a fight over the text that would accompany the image,” he says.

The finished mural includes a quote from a 1937 article in the Grand Junction Daily Sentinel superimposed on the image that reads, “Cattlemen, former employers and acquaintances all agree that fiction could produce no more colorful nor picturesque a character than Glass.”

This wasn’t Thomas’s first choice for the text, though.

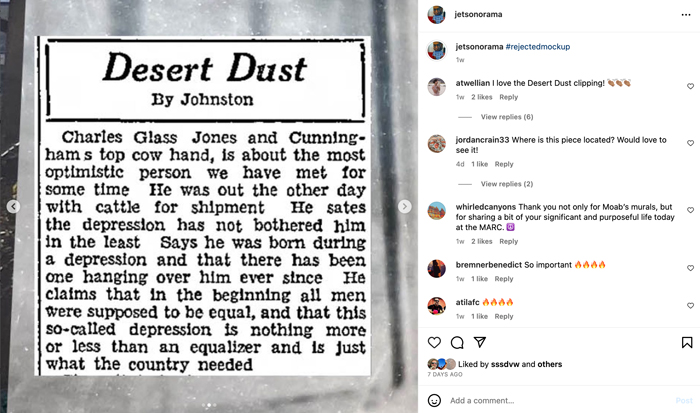

In an early September 2023 meeting, county commissioner Mike McCurdy objected to the proposed quote, saying it was “off-putting” because he thought it suggested that “in order for people to be equal, people need to be poor.” The quote Thomas originally proposed was an excerpt from a 1932 article published in the Moab Times-Independent.

It reads: “Charles Glass Jones and Cunninghams top cow hand, is about the most optimistic person we have met for some time He was out the other day with cattle for shipment He sates the depression has not bothered him in the least Says he was born during a depression and that there has been one hanging over him ever since He claims that in the beginning all men were supposed to be equal, and that this so-called depression is nothing more or less than an equalizer and is just what the country needed.” The punctuation and misspellings are true to the original quote.

“Those are beautiful and insightful words,” says Thomas. “All of us are created equal. The Depression brought everyone down to the same level, and it was an opportunity for us all to rise together,” he paraphrases.

“Sadly, there were people who were offended by that language,” Thomas says. “What I find fascinating is that the newspaper was willing to run Charlie Glass’s words in the context of the Great Depression, about which he’s speaking, but present day, those words have been censored.”

Morgan echoed his point, saying, “I find it frustrating that something published in a local newspaper in the 1930s was deemed inappropriate for public presentation in 2023.”

County commissioner Bill Winfield, along with county commissioner McCurdy, also disapproved of the quote, saying at the meeting, “In order for me to vote for this mural, the verbiage needs to be about the positive contributions Mr. Glass brought to the community, not the negative.”

In an interview later, McCurdy elaborates on why he opposes the quote. To him, the quote implies that “someone who is making money or working towards it, that you wouldn’t be counted as an equal.”

“If you’re not making it, you don’t want to be left out. You want to have the same equalities that we all have,” he says. “It goes both ways. I feel it on the less-money sense. But I could see it on the upper side of things, too.”

Morgan explains that the Glass mural had received pushback from the county, even before the text was brought into question.

“We had a really hard time getting approval,” Morgan explains, compared to the other mural Thomas proposed—a photo of three dolled-up women, the “Uranium Queen” and her attendants, participating in a parade celebrating the success of mining in Moab.

Thomas paired the photo of the Uranium Queen with a quote from a 1956 article in McCall’s magazine that called Moab the “richest town in the U.S.A.” The mural was installed outside of the Moab Museum, which supplied Thomas with its collection of archival photos to choose from for both murals.

Morgan says the murals were presented for separate approval while funding was still being sorted out. The Uranium Queen mural was approved first, but when it came time to review the Glass mural proposal, there were weeks of deliberations “during which the county lawyer demanded that the contracts—identical to those that had just been signed for the Uranium Queen mural—were insufficient and needed to be amended,” she says.

These edits to the contract were “ultimately dismissed as unnecessary months later,” she continues. But another technicality stood in the way: Moab Arts was informed the Glass mural was “dead in the water” because the project lacked a county staff sponsor.

Moab Arts started looking for a sponsor in June but wasn’t able to present the project to the county again until just three weeks before Thomas was meant to come to Moab for the installation on September 28. At this meeting, the mural was finally approved on the grounds that the quote was exchanged for something less “off-putting.”

Meanwhile, Morgan explains, Moab Arts was informed that the Moab Area Travel Council building, the county building where the mural was set to be pasted, would be demolished within the next two years.

“So we pivoted from a more permanent installation to a cheaper and less lasting method,” she says. During the installation, she talked to maintenance staff at the county building who were “unaware of any plans to demo the building, and said it would likely be a decade before the building comes down,” she says.

The materials Thomas chose for the Glass mural will most likely last two years. The Moab Museum had asked for something more permanent, and so Thomas used a more durable print for the Uranium Queen image, which should last five years or more, he says.

Thomas, who’s a doctor as well as an artist—he recently retired from working in a clinic on the Navajo Nation—says he’s “still trying to rationalize” the Uranium Queen mural during an interview after the installation.

As a physician, he had worked with countless Diné patients who suffered from the downstream consequences of radiation exposure from mining and uranium processing. Some of these patients became subjects of his photography, and later his murals. Much of Thomas’s work calls attention to the injustices of mineral extraction and processing on or near the Navajo Nation and the inordinate harm caused to Indigenous people as a result.

“I’m sorry that I didn’t push harder for there to be more context about the consequences of uranium mining, because just looking at the image alone, it doesn’t necessarily challenge the viewer to explore the detrimental legacy of mining,” he says of the Uranium Queen mural.

Mary Langworthy, public programs manager at the Moab Museum, posits another interpretation, though. “On one hand, it’s really happy and celebratory, acknowledging that uranium made Moab very affluent,” she says. “But also, it’s a little bit subversive and makes you stop and think about what the cost of being the richest town in the U.S.A. is.”

Thomas thinks the piece deviates from his larger constellation of work not just in the messaging, but in subject matter, too.

“I try to represent underrepresented groups, which generally aren’t people in the majority culture or white people. I started doing these murals in 2009, and I think this is the first one that I’ve done of white people,” he says of the Uranium Queen mural, which showcases three white women and their white parade car chauffeur.

As for the Glass mural, Thomas is more satisfied with the finished product, even though he had to compromise on the quote. This mural dovetails more seamlessly with his other work, much of which explores the history of early Black settlers in the Southwest and their relationships with Indigenous people.

“As an African American man from North Carolina who spent thirty-six years on the Navajo Nation and has good relationships with the folks in my community there, I just wondered about the history of African Americans here in the Southwest and what their relationships were like with Native people,” he says.

Thomas is the lead artist on the exhibition buffalo soldiers: reVision, currently on display at the Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center in southern Colorado. Part of the show tells the history of the all-Black army regiments that killed and displaced Indigenous people in their pursuit of westward expansion after the Civil War.

Glass was not affiliated with the Buffalo Soldiers, but he was an early settler of Moab.

The museum holds a few photos of Glass in its collection, including a shot of the Black cowboy on horseback. But Thomas chose this somewhat candid scene of domestic life because he loved “the ease, the sense of comfort they display,” he says.

“It puts them in a place of normalcy and, seemingly, acceptance. I really wanted to push that narrative because it’s easy for people of color to go into some of these Western communities now and be treated as if we have no agency,” he says.