The first Cey Adams retrospective displays more than four decades of the artist’s commercial collaborations with global brands and hip-hop visuals that include Public Enemy and Beastie Boys album covers.

In the world of hip-hop, you won’t encounter someone happier than Cey Adams. You see the big grin in Martha Cooper and Janette Beckman’s photographs—among the few to capture the New York City graffiti and street art scene in the 1970s and ‘80s—documenting the early days of Adams and his peers, who are tagging subways, walls, and even jackets.

A young Adams, between eighteen and twenty years old who would go on to design the cover art for Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet, is almost always smiling. Compare that to friends also documented at the time, like Jean-Michel Basquiat, who maintained a sensual stare and the occasional smirk. Keith Haring dons a dorky seriousness. Andy Warhol, a mentor, glanced with a gentle but cold glare.

Forty years later, he’s still smiling, as seen in a new show—and his first retrospective exhibition—spanning his multi-decade career.

Cey Adams, Departure: 40 Years of Art and Design includes the early photographs of Adams and his peers, his commercial work for brands like Def Jam and Mattel, and colorful paintings and collages overlaying his interest in Black identity, history, comic books, and popular culture. Lissa Cramer, director of Boston University’s Art Galleries (where the show was exhibited in 2022), and Liza Quiñonez of Street Theory, a New York-based contemporary art and design agency, organized the show, which runs through December 15, 2023, at the University of North Texas’s College of Visual Arts and Design Gallery in Denton, Texas.

Before designing corporate brands, Adams swindled capitalism: to get his materials, he stole art supplies to add unsanctioned commentary on public and private property. “Everything when I was young was about defying authority,” Adams told Debbie Millman for her podcast Design Matters in 2019. “It was part of the culture.”

But the act had a shelf life. “Graffiti ran its course, and I was getting to a different place,” he told Millman.

The Queens native eventually enrolled at New York’s School of Visual Arts, where he honed his lifelong use of clean lines and bold typography. His more sophisticated graphic style evokes Warhol while still rooted in his graffiti. At this point, it was the 1980s, and he was still in the movement but doing more commercial work, including for the Beastie Boys. That’s how Russell Simmons found him.

At Def Jam, he flexed his graphic design chops to make renowned album covers. More than two dozen of his album covers are on display at UNT, including Public Enemy’s Fear of Black Planet, one of his defining achievements, as well as the Beastie Boys’ Hello Nasty and Nikki D’s Nasty Little Girl. In addition to the retrospective show, Adams has been the subject of multiple exhibitions of late. Last year, a similarly named but separate show, Cey Adams: ETCetera: 40 Years of Art and Design, took place at the St. Paul, Minnesota-based NewStudio Gallery. Another solo show, Combinations, recently opened at the West Chelsea Contemporary in Austin.

Despite his accomplishments, Adams faced resistance from others in the predominantly white music industry. The music was not getting the same treatment from record companies’ executives in art departments. “They were stiff and didn’t understand the music we made. They dismissed me,” he says. “They didn’t understand hip-hop would take over the industry.” Those executives, he told Millman, were eventually fired.

As the genre went commercial, he didn’t shy from the founding themes. “When designing records, I didn’t want to court controversy but do something as beautiful as the work,” he told Millman, who also worked with him in the launch of the Hot 97 radio station in New York City.

With his fine art, some work straddles Black history and commercialization. In his 2019 series Our Revolution: Civil Rights Memories, six of which are on display, Adams superimposes paint over a mix of advertisements targeting Black people, clips from newspapers, and images related to Black history. Similarly, The Black Flag series repaints the American flag that, like the Revolution works, mixes collage and paint. One of them greets visitors at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C.

In the lauded Trusted Brands series, he adds words, images, and paint around logos for brands like Pabst Blue Ribbon, KFC, and Coca-Cola—the logos have been photocopied, torn up, and tinted. As the viewer dives deeper into the works, one may discover the deeper narrative embedded within.

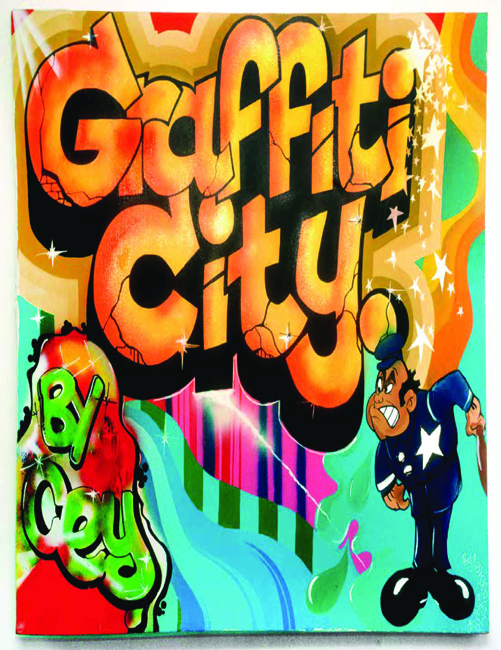

As he said in a 2022 lecture at the University of Michigan, “Using bright colors is a way to make the world feel good.” That’s clear in Graffiti City, an almost spray paint-like canvas blasting the work’s name, signed “by Cey” and featuring a police officer with a baton. It’s amusing and dark.

Bill Adler, a hip-hop scholar, says Adams “is a microcosm of the history of hip-hop. [It] started out as an impoverished subculture on the margins of society and moved into the mainstream with its integrity intact. Cey started out bombing subway trains and developed into a master of the graphic arts with a roster of brand name clients… all with his integrity intact.”