Center for Contemporary Arts Santa Fe started the year with a labor organizing win for staff, but not without union-busting allegations and three staff departures.

SANTA FE—Workers at the Center for Contemporary Arts in Santa Fe unionized on January 17, and are now represented by the Meow Wolf Workers Collective, Communication Workers of America Local 7055.

Meanwhile, some former employees are uncertain about CCA’s future as the organization hollows out its already small team amid the unionization effort. The cinema started this year with a team of nine, three of whom have since left in a spate of terminations and resignations.

The labor organizing landscape in the Southwest remains relatively arid despite the wave of unionization efforts sweeping arts and culture workers nationwide. However, workers at Meow Wolf in Santa Fe and Denver managed to win union recognition, and there’s a freshly minted union at the Denver Art Museum.

COVID-19’s onset imperiled an already fragile nonprofit arts ecosystem across the country. CCA Santa Fe is no exception. In 2023, the institution almost closed for good, but instead dissolved its visual arts wing, streamlining operations to only manage its cinema after a last-minute fundraising push. CCA has contracted with Chatter to provide management and programming services with Chatter’s partner organizations Tia Collection and Exodus Ensemble in the former gallery spaces.

There had been lots of issues throughout CCA’s troubled and spotty past that often involved board members overstepping.

Guiding this transition, No Name Cinema founder Justin Clifford Rhody became cinema director in February 2024, and Jayson Jacobsen was named cinema manager, after both had worked there for years. In October, CCA hired Dale Albright from the Lensic Performing Arts Center as development director.

Shortly after Albright’s arrival, Rhody says the board called him into a private meeting and offered him a $5,800 raise. As the person who oversaw the organization’s financials, Rhody didn’t understand how CCA could afford such generosity.

When the idea about forming a union floated around the staff, Rhody considered it a wise move, given his concerns about the board’s decision-making. “There had been lots of issues throughout CCA’s troubled and spotty past that often involved board members overstepping,” he says.

Milagro Padilla, a CWA campaign lead who helped organize CCA staff prior to the union vote, adds, “There was and still is a lot of uncertainty around the cinema itself, and people wanted to make sure that they had a voice in the cinema’s future.”

Employees notified the board about their intent to unionize in mid-November.

CCA agreed to voluntarily acknowledge the union, but under conditions that the employees did not agree with, setting up a stalemate about union eligibility that lasted nearly two weeks. Companies sometimes force negotiations like this to delay unionization, considered a union-busting tactic in some contexts, while employees sometimes do this to negotiate for better terms. CCA ultimately filed the petition for a formal election over the union eligibility of a single position—the cinema manager, Jacobsen’s role.

As cinema director, Rhody’s role met the supervisor criteria outlined in the National Labor Relations Act and he was not eligible to join. He still openly supported their efforts, but claims the board was not as enthusiastic.

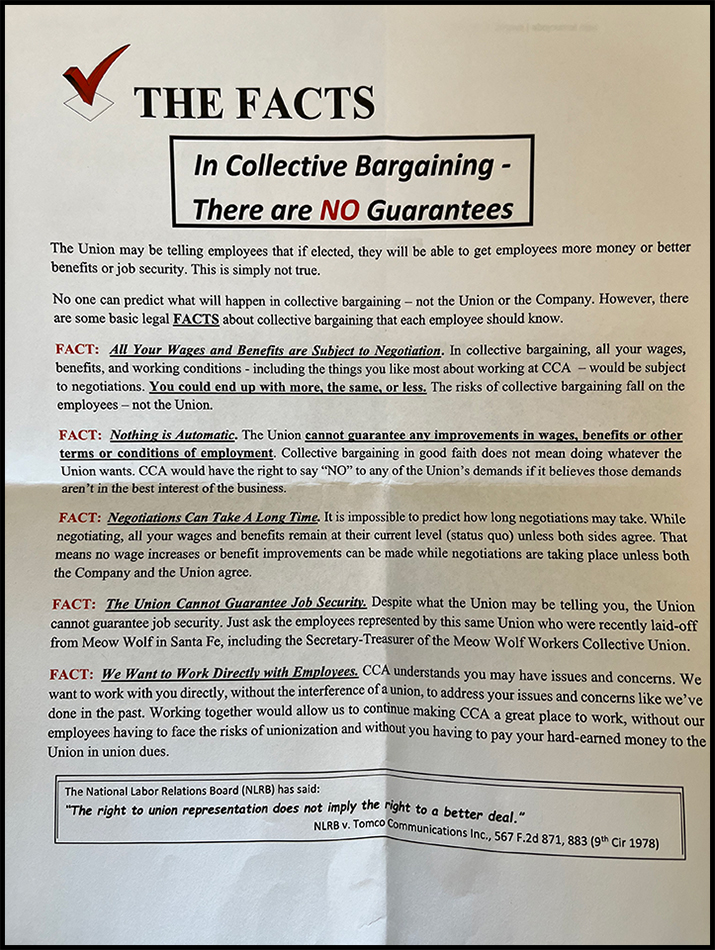

“They hired an attorney to carry out union-busting tactics, which were not really effective or well-thought-out, it seemed, and they asked me to be involved in it,” he says, citing a fact sheet that CCA’s Board distributed to staff at a meeting on December 31.

Despite what the Union may be telling you, the Union cannot guarantee job security.

The sheet outlines some “basic legal FACTS about collective bargaining.” It highlights that employee wages and benefits are subject to negotiations (“including the things [employees] like most about working at CCA”), that the union cannot guarantee any improvements in working conditions, and that CCA wants to liaise directly with employees without union intervention.

One of the points references the layoffs that occurred at Meow Wolf in 2024, which reads in part, “Despite what the Union may be telling you, the Union cannot guarantee job security. Just ask the employees represented by this same Union who were recently laid-off from Meow Wolf in Santa Fe, including the Secretary-Treasurer of the Meow Wolf Workers Collective Union.”

Padilla says this excludes key context. Even if layoffs happen, unions may be able to negotiate for more favorable outcomes, such as voluntary resignations, continued health insurance benefits, and severance pay. He says workers were afforded significant protections in the recent union-mediated layoffs at Meow Wolf compared to the layoffs in 2020, which happened before the union was formed. “We were able to ensure that people got a fair deal,” he adds.

CCA declined to comment on my inquiries about the fact sheet.

On January 1, Albright was promoted to executive director. The following day, Rhody says Albright told him that his position had been written out of the 2025 budget, citing a decline in ticket sales as the reason. Rhody and Jacobsen were both asked to remove their personal belongings from their shared office to make space for Albright.

“Ticket sales were about 12% lower, but we were going against the year prior, which was… the Oppenheimer and Barbie summer, which was massive,” says Rhody. “However, all of this other work that I’d done to restructure, lower operating expenses, and things of that nature, when you look at… our net income after expenses, we were ending this year at a 65% increase.”

Meyer informed Rhody that he wasn’t terminated, but rather, had voluntarily resigned.

Rhody emailed the board an acknowledgment of termination on January 3. In the email threads I reviewed, board chair David Meyer informed Rhody that he wasn’t terminated, but rather, had voluntarily resigned. Albright told Pasatiempo that “[Rhody’s] resignation… came as a surprise”.

CCA declined to comment further on matters related to personnel separation.

Two weeks later, the staff finally voted to form a union. Of the seven eligible voters, four voted in favor; one voted against, and one was away on vacation. CCA challenged the fifth “yes” vote from the cinema manager. Despite CCA’s opposition to his favorable vote, Jacobsen is technically still represented by CWA during the collective bargaining process until determined otherwise.

The excitable atmosphere typically following a labor organizing win was clouded by what one former employee describes as a growing disconnect with leadership. “[Rhody] leaves, and… day-to-day operations are fine, but the mood was just really bad,” says Luna Galassini, who recently left her role as a box office employee. “There was a lot of stuff that just started falling through the cracks.”

Galassini mentions a recent film screening as a flashpoint for the widening chasm.

On January 26, the cinema screened the documentary OCTOBER H8TE: The fight for the soul of America (which has since been renamed October 8) through its rental partnership with the Santa Fe Jewish Film Festival.

When I sort of laid out why this movie was a genocide denial movie, [Albright] said… it was this terrible mistake.

The film characterizes protests calling for the end of Israel’s military onslaught in Gaza—deemed a genocide by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and a UN special committee—as antisemitic and aligned with terrorists, mirroring the rhetoric the federal government and some universities are using as cause to criminalize pro-Palestine student activists.

Galassini says CCA staff voiced widespread opposition to the film. “When I sort of laid out why this movie was a genocide denial movie, [Albright] said he was horrified, and it was this terrible mistake,” she recalls. “But he not only greenlit the movie, he also told [Jacobsen] to promote it on the website.”

Ultimately, CCA proceeded with the screening, although Jacobsen refused to market the event on CCA’s website and social media pages. Galassini resigned at the end of January.

Albright did not respond to specific questions regarding the screening, but provided a written statement that reads in part, “As an independent, non-profit arthouse cinema, CCA is dedicated to maintaining the delicate balance between elevating diverse viewpoints while respecting the deeply-held beliefs of our community.”

The cinema roster roulette culminated with Jacobsen’s termination on March 1. His three-page termination letter details “repeated unsatisfactory performance” and alleges that Jacobsen failed to perform his duties beginning in January 2025, around the time Rhody left.

Prior to Jacobsen’s firing, CCA did not provide notice to CWA as required by Sections 8(a)(1) and (5) of the NLRA. Padilla says this is a “union-busting tactic,” and that CWA filed an Unfair Labor Practice complaint with the NLRB following Jacobsen’s termination.

If you’re a worker reading this, you have power. Organize your workplace.

Shortly after Jacobsen’s dismissal, CCA hired Kristin Pulatie, former director of programming and partnerships at Highgarden Entertainment, as cinema managing director.

“CCA looks forward to a bright future supporting our Santa Fe community,” reads a statement from CCA.

Beyond sharing his termination letter, Jacobsen declined to comment on the situation due to the pending complaint. Despite the elimination of two employees represented by CWA, the union at CCA is there to stay, which Padilla says makes him hopeful.

“If you’re a worker reading this, you have power,” he says. “Organize your workplace.”