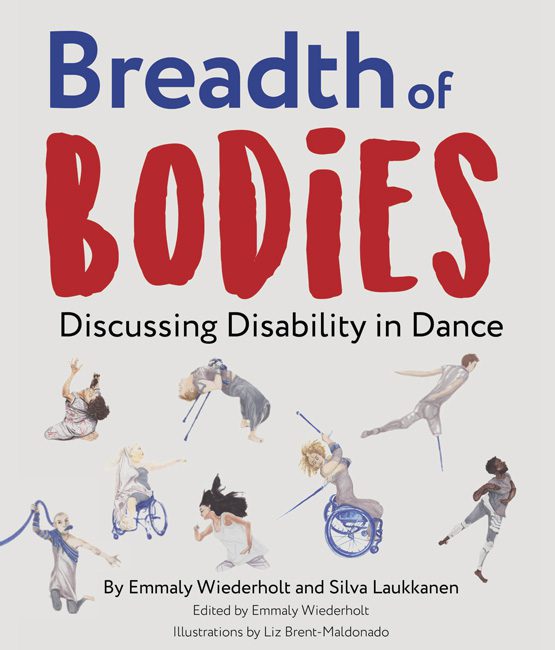

Breadth of Bodies: Discussing Disability in Dance spotlights the voices, experiences, and art of dancers with disabilities.

According to a 2018 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in four people in the United States identifies as having a disability that impacts their life in a major way. “What if the dance world reflected that statistic?” ask Breadth of Bodies co-authors Emmaly Wiederholt and Silva Laukkanen.

The striking book, which serves as a platform and amplifier for some of the least represented voices in dance, comprises interviews with thirty-five dancers from around the world across multiple dance genres, spanning a spectrum of experience with disability. Breadth of Bodies is presented in serial Q + As, centering the voices of dancers in answer to questions about their careers, artistic practices, training opportunities, encounters with stereotyping, and thoughts on the current state of the field. Dynamic and compelling illustrations by Liz Brent-Maldonado depict the artists’ messages and dance forms.

Beyond making for clear, at-your-own-pace reading, the book’s format is a deliberate choice.

“It was very important to feature the dancers,” says Laukkanen, an Austin, Texas-based community dance educator and long-time advocate for disability inclusion in dance, in an interview with Southwest Contemporary. Wiederholt, an Albuquerque-based dancer, writer, and diversity advocate who also spoke with us, agrees. “I believe in letting artists speak for themselves.”

Taking lead from that example, here are dancers’ statements quoted from the book and from interviews with local New Mexico artists.

Alice Sheppard, founder and artistic director of Kinetic Light (U.S.)

The history of disability and dance in the U.S. goes back a long way, but the dance world does not know it. I want to build a network of legacy by naming the disabled dancers who have influenced me: Stephanie Bastos, Rodney Bell, Marc Brew, Laurel Lawson, Bonnie Lewkowicz, Kitty Lunn, and Judith Smith.

Jerron Herman, interdisciplinary artist and dancer (New York)

People are like: “I don’t know what physically integrated or disability artistry means, so I am not going to learn. I don’t know what it is, so I’m not going to engage.” That reaction is in tandem with ignorance and fear.

Charlene Curtiss, founder and director of Light Motion Dance Company (Seattle)

It’s great to have festivals that are all about showcasing integrated dance. Those are unique and extraordinary experiences. But integrating dancers with disabilities into the mainstream is also very important and shows something else: it highlights equality, acceptance, and new ideas.

Integrated dance has finally risen to the level where we can start being critical about it. Some of it’s good, and some of it’s bad. It’s not “all good because it exists” anymore.

Yulia Arakelyan, co-founder of Wobbly Dance (Portland)

My biggest frustration is when people (and you see this a lot in articles and inspiration-porn videos) say things like: “despite not having arms and legs….”, “Despite…

NOOOOOO! It’s not “despite.” It’s because of our unique bodies that we are the amazing dancers (and people) that we are.

More can be done to include more diverse bodies in this field, like more professional dancers who use powerchairs, ventilators, or people with developmental disabilities. The physically integrated dance world can be very exclusive as to the type of disabled bodies that are hired and seen.

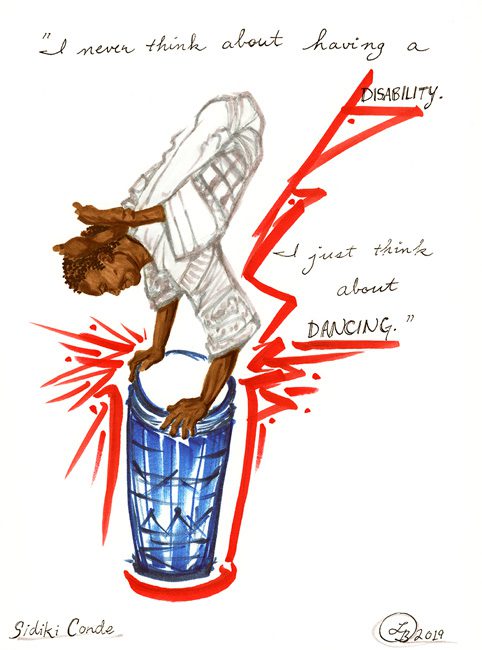

Sidiki Conde, founder of Tokounou All-Abilities Dance and Music Ensemble (Guinea and New York)

Everybody can dance. Dance is about happiness, and everybody needs happiness. I am disabled, it’s true. But, at the end of the day, dance is dance. Find your happiness.

Toña Rivera, dancer and teacher (Albuquerque)

Dance teachers should give people with disabilities the opportunity to dance.

(Rivera, who spoke with Southwest Contemporary for this article, isn’t featured in Breadth of Bodies)

Orli Adia, University of New Mexico dance and psychology student (Albuquerque)

My first semester, my friend and I performed a duet about the relationship between a disabled and non-disabled dancer. It explored the curiosity, discomfort, and the beauty of what that relationship has to offer.

I wish people knew how important accessibility is. We’re limiting the number of people who can dance and it’s stopping growth.

(Adia, who spoke with Southwest Contemporary for this article, isn’t featured in Breadth of Bodies)

This point comes up again and again. Accessibility—from physical studio spaces to teacher training to leadership opportunities—is crucial so that anyone who wants to dance is able to.

The quotes shared here don’t scratch the surface of the creativity, experience, and perspective explored in Breadth of Bodies. Wherever you stand in relation to this field, this book is an excellent resource to learn more about the amazing range of talent, artistic approaches, and philosophies embodied by the dancers and their work.

Breadth of Bodies is scheduled to come out April 7, 2022 on Amazon, Goodreads, and other platforms. There is an audio version read by Sami Kekäläinen who identifies as a creative with a disability, as does the book’s designer, Christelle Dreyer. You can also access many of the interviews and illustrations at Wiederholt’s blog, Stance on Dance.