Cecilia Alemani rolled out an exhibition like no other in Santa Fe. Part funhouse, part uncanny factory, part archive—its visionary weirdness will hit everyone a bit different.

Once Within a Time: 12th SITE Santa Fe International

June 27, 2025–January 12, 2026

SITE Santa Fe + other venues across Santa Fe

The exhibition opens with a sudden moment of uncanny. Three people stand motionless near a wall covered floor to ceiling with an abstract photograph. The photograph is a blurred, extreme close-up of Surrealist Meret Oppenheim-designed gloves, monumentally scaled, by Louise Lawler. The people are hyperrealistic, life-sized sculptures by Gisèle Vienne. You might breeze past them, eager to embark on your journey through the extensive and wide-ranging SITE Santa Fe International, titled Once Within a Time. But that opening note of high weirdness might linger, an undertone of surreality.

Dolls, puppets, mannequins, and zombies—non-living human figures devised for play, theater, commerce, or horror—appear at various junctures of the exhibition. An anatomical Venus lays supine behind a curtain of red gauze. Mannequins arranged in family groups await nuclear bomb tests in photographs staged at the Nevada Test Site. A doll factory is embedded in a cannabis shop downtown. And in one film, a sleep-deprived soldier encounters a zombie-like army, their eyes sewn shut (the film, by Ali Cherri, is playing at the New Mexico Military Museum).

The show’s organizer Cecilia Alemani is, by all accounts, a star curator, most well-known for her exhibition at the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022, The Milk of Dreams, which hosted over 800,000 visitors, breaking the attendance record of the Biennale (even in the midst of a global pandemic). Once Within a Time isn’t on the scale of Venice, but it spans fourteen venues across Santa Fe, featuring over ninety artists and three hundred objects.

So what does it mean for SITE to bring in a superstar to mount the most ambitious SITE International ever? When the museum announced the show, it certainly sent a ripple of excitement through the art community in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and the wider Southwest. Would her version of the Southwest resonate? Was this part of a larger plan to turn Santa Fe into an “essential art outpost,” as a New York Times headline later claimed? Are we on the map now?

Alemani is not just any star curator, however. And she didn’t just fly in a roster of biennial artists and big names. Her approach, rather, runs deep and goes hyperlocal. Her work in Santa Fe is deeply informed by close consultation with anthropologist and historian Estevan Rael-Gálvez and navigates the complex historical forces at play in the region. The words curator and curandera, or traditional healer, after all, derive from the same Latin root: curare, to care for.

The show strikes a sweet balance between international artists and the Southwest’s very own. And, like in The Milk of Dreams, Alemani wields historical figures (or “figures of interest”) and objects as lenses for deeper understanding. She draws connections between the past, present, and future, creating a palimpsest or a multi-layered story of a place within and through time. Which is very much how Santa Fe functions, with all times visible, like the strata of a canyon.

“The story does not end. Rather it revolves on a wheel of telling,” wrote N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa) in his 2022 poem “In the Telling,” evoking a cyclical logic that aligns with Alemani’s curatorial methodology. Momaday is one of the first “figures of interest” you encounter, and, with his passing in 2024, one of the pantheon’s closest voices to our time. “There are many stories in the one,” he wrote. “And indeed there is one story in the many.” Storytelling as both monadic and multitudinous serves as a guiding principle throughout the exhibition, where echoes rebound.

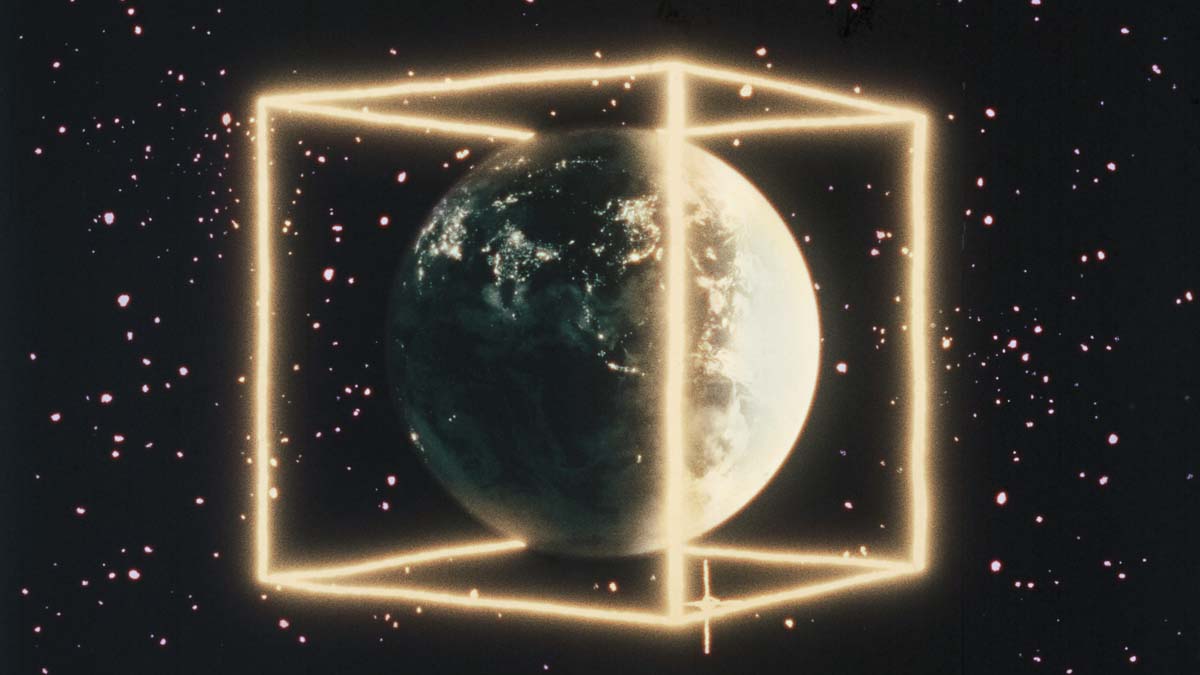

Godfrey Reggio’s 2022 film Once Within a Time, which lends the exhibition its title, also offers a key to the exhibition, with its surreal imagery delivered with wordless theatricality. Its allegorical message—humankind on the brink, torn between mindless, tech-driven destruction and the salvation of nature—comes through so crystal clear that a child could easily understand it. Time cycles through successive catastrophes in what Reggio has described as “a bardic event where children resist their destiny,” culminating with a question written in multiple languages in the final scene, “Which age is this, the sunset or the dawn?”

Storytelling as both monadic and multitudinous serves as a guiding principle throughout the exhibition, where echoes rebound.

A figure who straddles time, the titular curandera of Rudolfo Anaya’s 1972 novel Bless Me, Ultima fittingly came to the author in a dream. In the book, Ultima, another of Alemani’s “figures of interest,” comes to live with Antonio and his family on the llano of Eastern New Mexico when he is a very young boy, and proceeds “to open Antonio’s eyes” to the magic and secrets of the natural world. She is a conduit, a shaman with ancient practices that sometimes come into conflict with the Catholic Church and the “progress” of the post-War world, an age that the author has lamented “has forced us to enter a linear time.” Instead, for Antonio, upon meeting Ultima: “Time stood still, and it shared with me all that had been, and all that was to come.”

That point of no return of the postmodern age, of course, is the atomic bomb, a brand-new evil unleashed right here in New Mexico, imbuing the healing landscape with an invisible poison. Once Within a Time taps generously into this well of the nuclear uncanny. It’s in the upturned bed by Joanna Keane Lopez, referencing a literal bedroom where the plutonium core of the first nuclear bomb was assembled at the Trinity test site. It’s hinted at in the landscapes by Transcendentalist Agnes Pelton and contemporary artist Diego Medina, where mystical forms of light in the sky could signify sinister origins. Most starkly, it’s present in a video by Guillermo Galindo about the nuclear program with footage from an abandoned missile silo located outside of Roswell—which “eats itself” as it plays again and again, the sound and video becoming more distorted with each turn.

Galindo’s work appears at Finquita, on the grounds of the old Shidoni gallery and foundry up north in Tesuque. The artists take full advantage of its surroundings there, situated on a campus of cavernous industrial buildings. While you could spend hours wandering through the main exhibition hall at SITE Santa Fe, viewing every angle and absorbing it all, the rest of the exhibition sprawls through the city and its environs. It’s well worth it to venture beyond, where Alemani’s approach of overlaying different times, juxtaposing historical settings with newly commissioned works, really stands out.

Here, the curator/curandera becomes a fulcrum by which contemporary artists leverage the otherwise unremitting weight of Santa Fe’s long history. The most breathtaking of these projects takes place in the St. Francis Auditorium at the New Mexico Museum of Art, in a conversation between contemporary painter Maja Ruznic and early 20th-century artist Donald Beauregard. Three panels from Beauregard’s six-part series romanticizing the Franciscans’ colonization and conversion of New Mexico—installed in arched niches around the auditorium—are now eclipsed by Ruznic’s paintings of abstract, gauzy figures looming in greens, ochres, viridians, and lavenders. The effect is haunting and potent.

In the nearby Palace of the Governors, Daisy Quezada Ureña also excavates colonial histories—quite literally. Her plunder, on view in custom vitrines, includes a Pueblo bowl, historic pistols, and about a cubic foot of soil collected from the construction site for a new Georgia O’Keeffe Museum building. Three fragments of 17th-century iron bells, relics from the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, lie on the dirt in a niche in an exposed adobe wall. Various garments that the artist has alchemized into porcelain also hover within vitrines, from a shirt worn by a journalist to a plutonium handling facility in Los Alamos, to a child’s blouse, mounted up high overhead, like a little saint ascendant.

Reggio calls the children that appear in all the cycles of his film—from its Edenic start through its various collapses—the “hero children.” The exhibition as a whole, with its dolls and puppets and playfulness and weird turns, seems meant to be experienced through the eyes of a child.

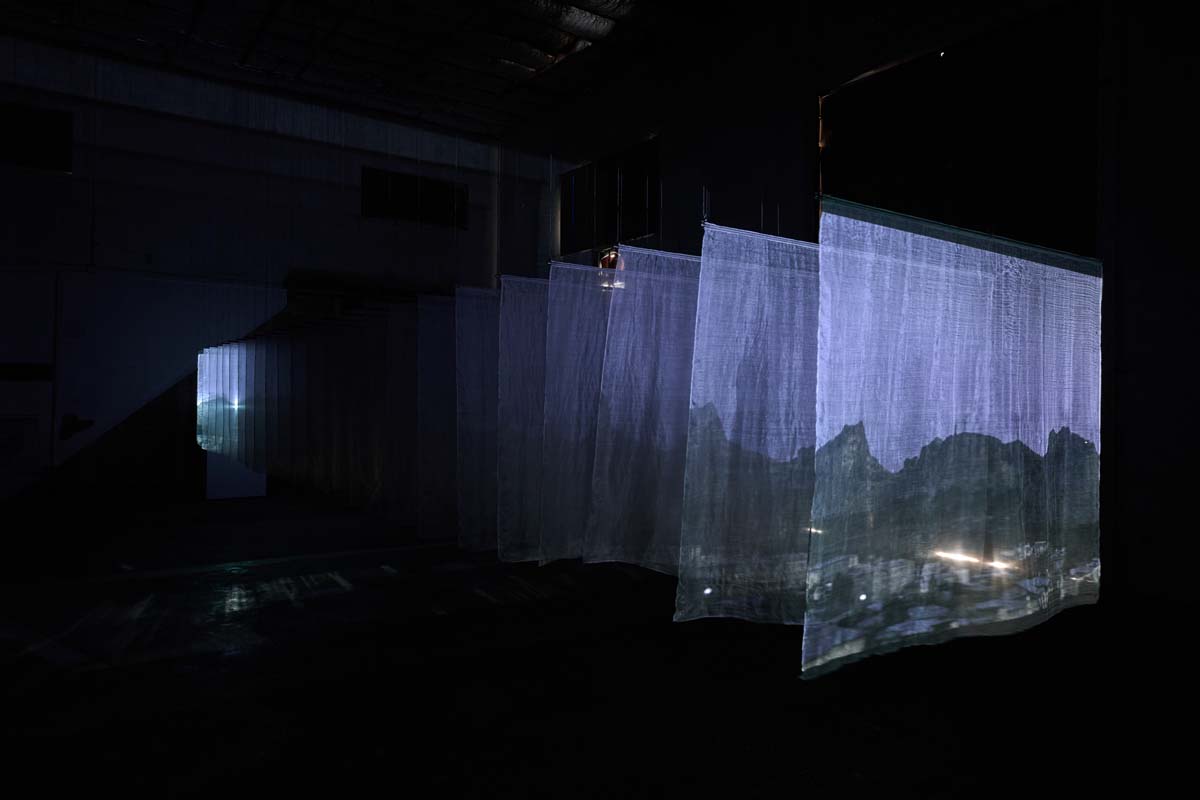

The intense colors of each room in the main exhibition hall, split by transparent colored curtains, stir pure enjoyment. The immersive delight of Zhang Xu Zhan’s stop-motion-animated mouse-deer outwitting crocodiles, on view in a basement room of the Museum of International Folk Art, especially appeals to a child’s sensibilities. As well, the unsettling and supremely immersive installation by Korakrit Arunanondchai at Finquita is one that inspires a visceral response and child-like wonder. (Though that one might be a little too scary.)

It remains to be seen what the ‘Alemani effect’ on Santa Fe might become.

So while one’s adult intellect will find much to grapple with in the exhibition, on a fundamental, sensory level a child’s-mind response to it is entirely appropriate and even advantageous. The exhibition is part fun house, part uncanny factory, part archive—and its moments of visionary weirdness will hit everyone a bit different.

In reporting about the exhibition prior to its opening, Jordan Eddy asked Alemani if the playfulness of her work means that she considers children as part of her audience. Art as fun, play, learning, and enjoyment are important for Alemani in her curating, she replied. “It’s a space where your ideas can be effervescent and can really find a fast pace to think and to be creative and productive. And maybe that’s the mind of children.”

It remains to be seen what the “Alemani effect” on Santa Fe might become. (Or, for that matter, how the “Santa Fe effect” might manifest in her work.) What can clearly be seen, and felt, is not just the feat of a city-spanning exhibition, but an endeavor of care and honor for the region and our artists. Alemani, the curator or the curandera, was summoned here to open our eyes, and time stood still, just for a moment.