Newly discovered letters revive a writer’s quest to discern why two Taos-based modernist artists had an outsized impact on her family—but not art history.

This article is part of our Living Histories series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 9.

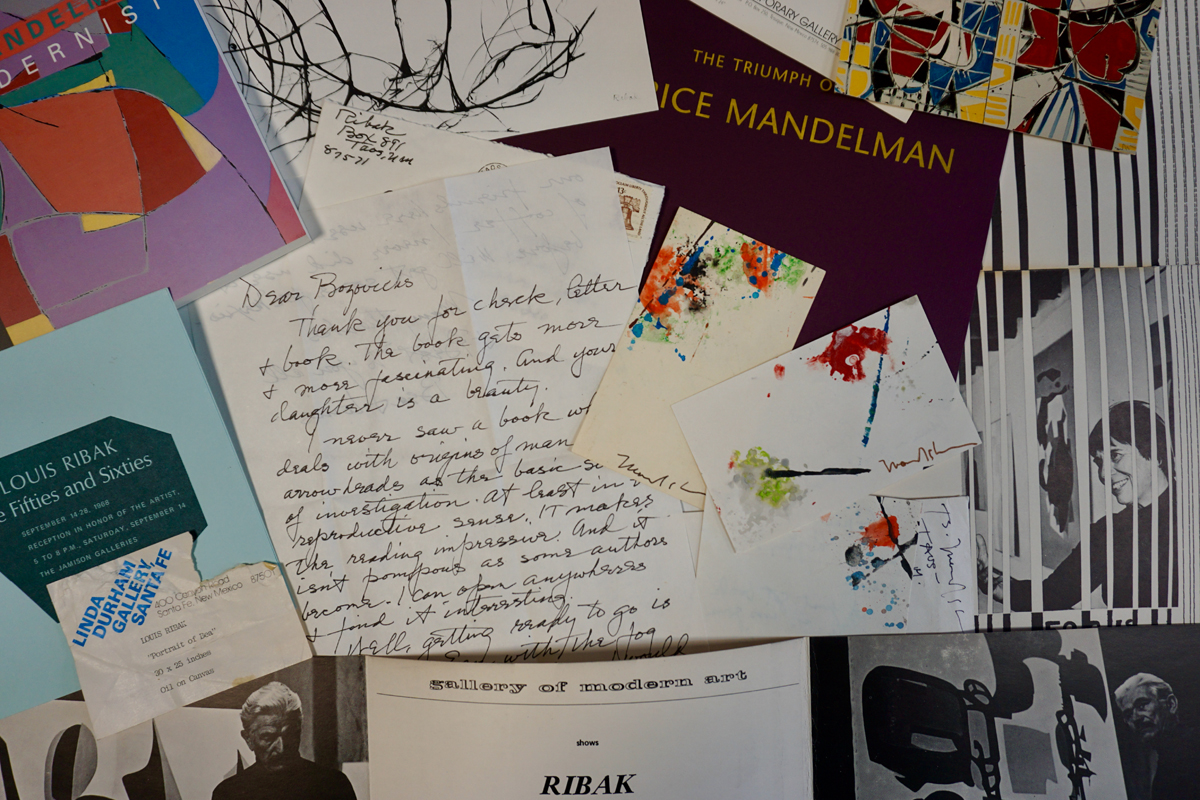

Six weeks after my grandmother passed this summer, my family discovered loose correspondence among her effects. One letter postmarked in Taos, New Mexico, had traveled to Denver, Colorado, for a modest fee of thirteen cents in 1978. “Dear Bozovichs,” read the familiar scrawl. “Thank you for [the] check, letter + book. The book gets more + more fascinating. And your daughter is a beauty.” This “daughter” was likely my mother, the younger of two sisters often referred to as “the musicians” in comparable epistles, who graduated high school later that year.

I rifled through more notes from Taos and airmail from San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. Some were splattered with paint and others heralded exhibitions: Santa Fe’s Jamison Galleries hosted a Fifties and Sixties show in 1968, and an August Review opened at Shidoni Contemporary Gallery in Tesuque, New Mexico, on August 4, 1989. The missives were adorned with anecdotes and payment requests, philosophies and gripes about the weather. All bore testimony to the idiosyncratic goodwill sometimes forged between artists and their collectors.

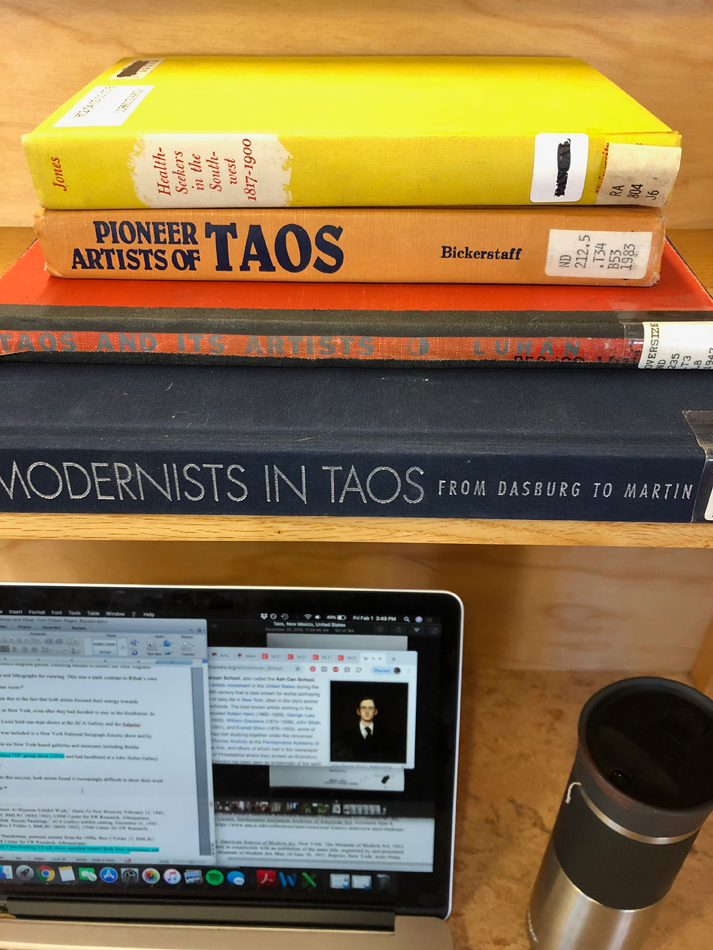

Amid my grief and scholarly fascination, my thoughts transported me to the University of New Mexico’s Zimmerman Library in 2018, when I had last studied this handwriting. Then, as now, I hoped to find myself in someone else’s archives and to comprehend my family’s minor, yet personally consequential friendship with (and patronage of) two locally prominent artists—lesser-known outside of their regional orbit—whom I would never meet in person.

I realize I’m asking more for my work than many others are, but I do fewer and fewer works that I like myself.

Louis Leon Ribak (1902–1979) and Beatrice Mandelman (1912–1998) had established themselves in Taos long before my grandparents walked through their door in 1968. The artists had departed New York City to holiday in New Mexico twenty-four years prior, only to stick around in the Valley and earn local notoriety for their modern aesthetics.

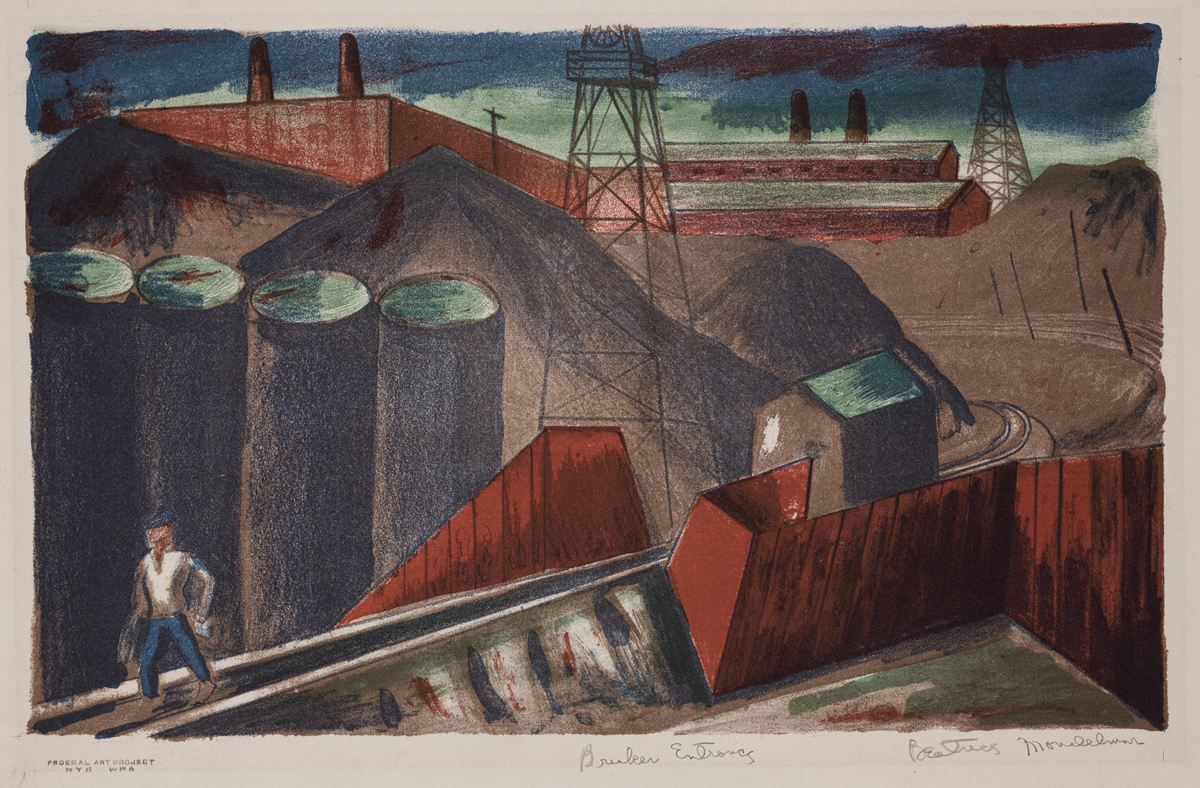

Though they began art making in the predominant Social Realist style of pre-war America and contributed to the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project, Mandelman and Ribak’s careers were marked by independent, yet parallel shifts into abstraction over the course of the 20th century. Their persistent (though fraught) relationships with Abstract Expressionist circles in New York, Mandelman’s studies with Fernand Léger, and their yearly travels to Mexico and elsewhere, influenced what Mandelman called their “search for the essence” of creating. And by the 1960s, they had developed prolific careers among the ad hoc and loosely-cohered group of artists now known as the Taos Moderns.

Family lore, interviews I conducted in 2019, and other recent discoveries drafted in my grandmother’s hand place the Bozoviches in this milieu at least once a year for almost three decades. They hadn’t intended to collect art. But whispers about the significance of Taos’s culture reinforced by Gene Kloss‘s etchings at Gallery A (which is now defunct, like Jamison and Shidoni) piqued their interest in the state’s art scene.

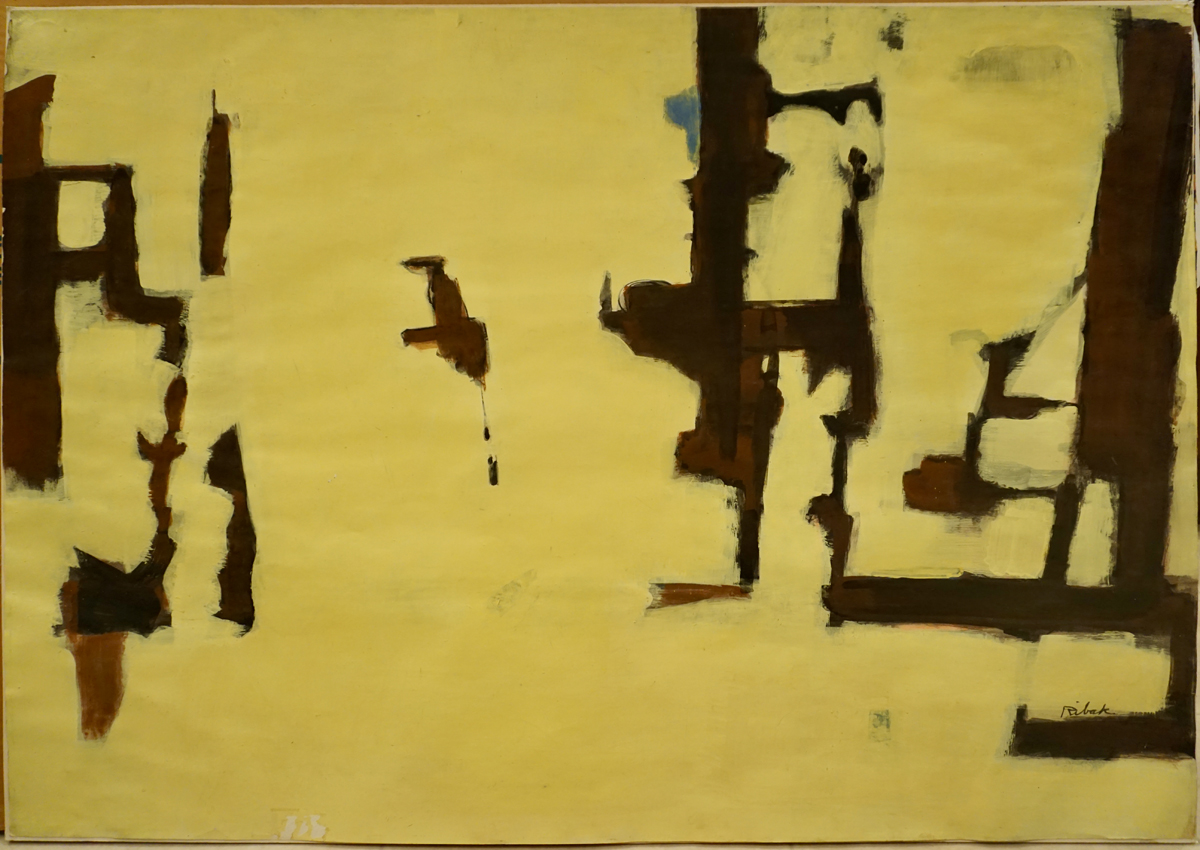

A chance encounter with my grandfather’s all-time favorite painting—a brown-and-yellow tempera from Ribak’s Aegean Series—crystallized a sense of kinship with the artists. The gallerist directed my grandparents toward Ribak Lane, where they would spend afternoons catching up and surveying new works while my mother and aunt ate withered apples from the coffee table. My grandparents also began collecting over nineteen artworks, and may have helped keep the artists afloat in scant years. The couples spoke frequently of money in their letters back and forth, but always with affection. “I realize I’m asking more for my work than many others are,” wrote Ribak to my grandmother in 1971. “But I do fewer and fewer works that I like myself. But don’t worry. Your musicians will yet save the day.”

I not only wanted to know how they survived after moving out of New York, but why they had stayed.

Mandelman and Ribak’s story unfolded for me in the UNM archives in November and December of 2018. As an older undergraduate at the University of Denver with years of false starts at my heels, I had settled on the lives of “Bea and Louis” for my thesis topic, in part because no one in my art or history programs had heard of either artist. But in truth, I wanted to meet them myself. I was also uncertain of my career path, skeptical that I could support myself in Denver’s own “regional” art scene.

Holding onto Bea and Louis through my family’s stories, I traced the couple to the Harwood Museum of Art before tackling their papers at the Zimmerman Library in Albuquerque. I not only wanted to know how they survived after moving out of New York, but why they had stayed—and perhaps find a road map for myself in the process.

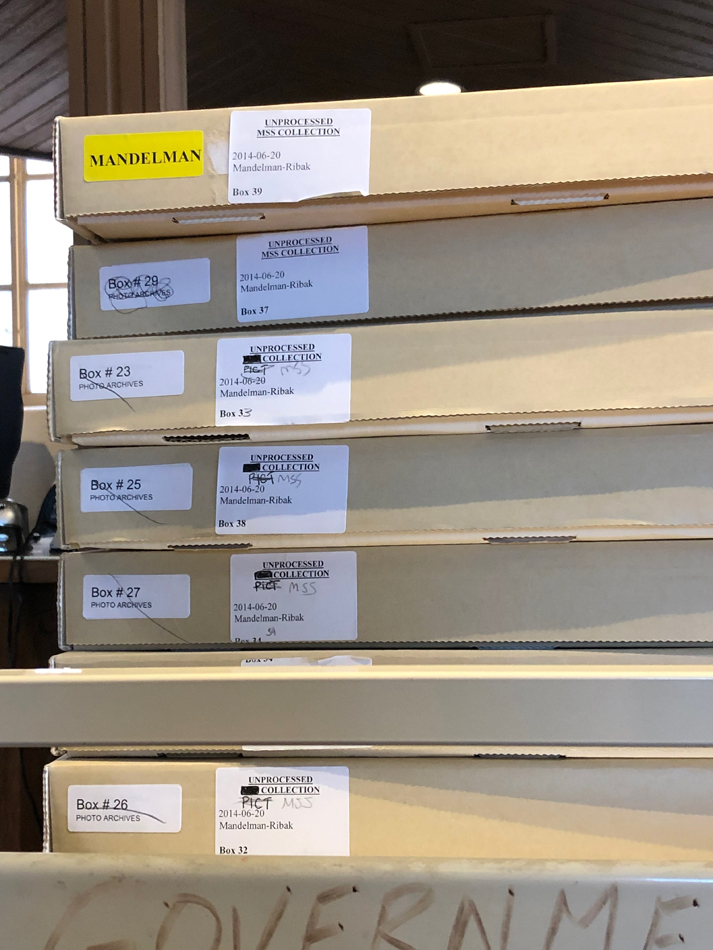

And so came thirty-nine archival boxes out of storage at UNM’s Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections, some unprocessed, all brimming with journals, interviews, passports, rejection letters, and other ephemera. Each box was a revelation, bearing proof that these figures from family legend were, in fact, real. I even found a photograph of my smiling grandmother next to Bea, my mother, my aunt, and Louis. With every folder I came to know Louis’s arabesque penmanship and love of nature, Bea’s poems and her incisive (sometimes derisive) attitude about regionalism. More importantly, I better understood how difficult it was for the couple to find critical or commercial success anywhere but in the Southwest.

Mandelman and Ribak’s reasons for leaving New York City in 1944 were complicated, and they maintained divergent outlooks on the consequences of their move. Friends and interviewers surmised that Ribak initiated their departure from the East Coast, either on doctor’s orders (he suffered from asthma); at the influence of his mentor and fellow New Masses newspaper contributor, Ashcan School painter John Sloan; or because of Ribak’s dislike for New York’s aesthetic discordances.

But the artists told my grandparents something slightly different. Visits with Bea and Louis often prompted a “Taos versus New York” debate—both artists’ mistrust of dealers and a healthy distaste for the city’s cramped influences had bred a discontentment that only the high desert could soothe, even if Bea remained skeptical about where they landed.

Ribak found the Southwest to be expansive and generative, if sometimes sparse: “The variables of nature, the seasons’ interchangeablenesses, warms where you expected cold, pleasant where you expected harsh, understandings where + when one needed it most. That’s what made me stay + stay + come back again + again,” he wrote in an undated journal entry.

The opposite was true for Mandelman. “I do think in my case, and of course in Louis’ case too, we would have been artists, no matter what,” she told Smithsonian Institute interviewer Sylvia Loomis for the Archives of American Art in 1964. “And there are many people that might not have, because in spite of everything we still continue here when there’s no warm climate for it. It’s a terrible situation out here, I think.”

Did place really matter in art? The couple’s big-city rejection letters suggested that it did.

This discord guided my late-night thesis writing sessions in 2019. Did place really matter in art? The couple’s big-city rejection letters suggested that it did. Yet I appreciate now what I did not then: that my grandparents would never have met Bea and Louis, might not have collected their art, could not have formed a friendship with them lasting over a quarter-century if the artists had never made the move. So though several works in the family collection were scattered to the four winds by the time I started my thesis, I cradled them in paragraphs and footnotes, reflecting often on why I was here at all. As Bea scrawled in a May 1971 journal entry: “Does a living creature understand its origin and can one have the ability to undertake to design the future[?]”

Ribak and Mandelman stayed in Taos and remained fiercely prolific up until their deaths in 1979 and 1998. In the years since meeting both of them in the archives, I have thought often of Ribak’s Portrait of Bea (ca. 1944), an oil that hung in my grandparents’ living room before Harwood Museum acquired it in 2013. I remember her enigmatic face, his spiky signature, and the desert landscape beyond a red curtain. Bea appears less inscrutable and more pensive to me now than she did before our encounter in the library.

Truthfully, both Bea and Louis remain largely unknown to me, constrained as they are by time, geography, and others’ memories. Readers who knew them personally may balk at some of my characterizations. But I finished my thesis and graduated college after eight tough years, began contributing art reviews to local magazines, and landed my first job in museum communications because of them. My grandfather refers to their first meeting in 1968 as “the day everything changed.” I, for one, am inclined to agree.