With a keen eye and a bold approach, Shayla Blatchford’s Anti-Uranium Mapping Project confronts the damaging impact of unethical mining on Southwest Indigenous lands.

“Capitalism, AI, this technology… it separates you from your body and us from each other,” Shayla Blatchford (Diné) says sleepily to me over the phone. She is in New York, resting after back-to-back engagements: a solo exhibition at the University of New Mexico; a group show at the Center for Fine Art Photography, Fort Collins; an Indigenous-led mining conference in Montreal; a guest lecture at Yale University; and most recently, karaoke night. She would have gone to bed early (what with all the work and travel), but her friends from Taos were in town and one of them had never booked a private karaoke room. “They were really having a moment,” she explains, “so I had to see it through.”

This unique mix of critical focus, wry playfulness, and fierce support for those around her infuses the way the Santa Fe–based photographer moves through the world. Her direct yet buoyant point of view is as welcoming as it is galvanizing, imbuing her documentary work, Ivy League presentations, and road trips copiloted by her dog, Dibé, with a serene sense of import. Though she may shrug off her prodigious talent with a factual “I’m an observer,” you do gain the ability to hold sprawling complexity with clarity and care when you look at the world through Blatchford’s lens. It is to all of our benefit that for the past four years Blatchford has turned her skillful eye toward the ecological impact of mining on Indigenous lands of the Southwest.

Blatchford’s Anti-Uranium Mapping Project is a robust, multidimensional educational platform supported by illustrious funders such as Anonymous Was a Woman, New York Foundation for the Arts, Fractured Atlas, and, most recently, a 2025 Creative Capital Award. The project was born out of a late-night Google Maps sojourn home. Though she grew up in Southern California, surfing all day when school wasn’t holding her interest, it was Blatchford’s childhood visits to her aunt on the Navajo Nation that took root in her developing self-conception. Governmental policies like the Indian Relocation Act had torn her from her family before she was even born, so she resisted this forcible fragmentation however she could—even by means of satellite. It is perhaps perversely fitting that this technology of corporate mapping and surveillance capitalism revealed to her yet another colonial violence: her path home was tarnished by a mine scarring the earth.

Blatchford unflinchingly documents instances of environmental racism and violations of tribal sovereignty—which she also feeds to AI.

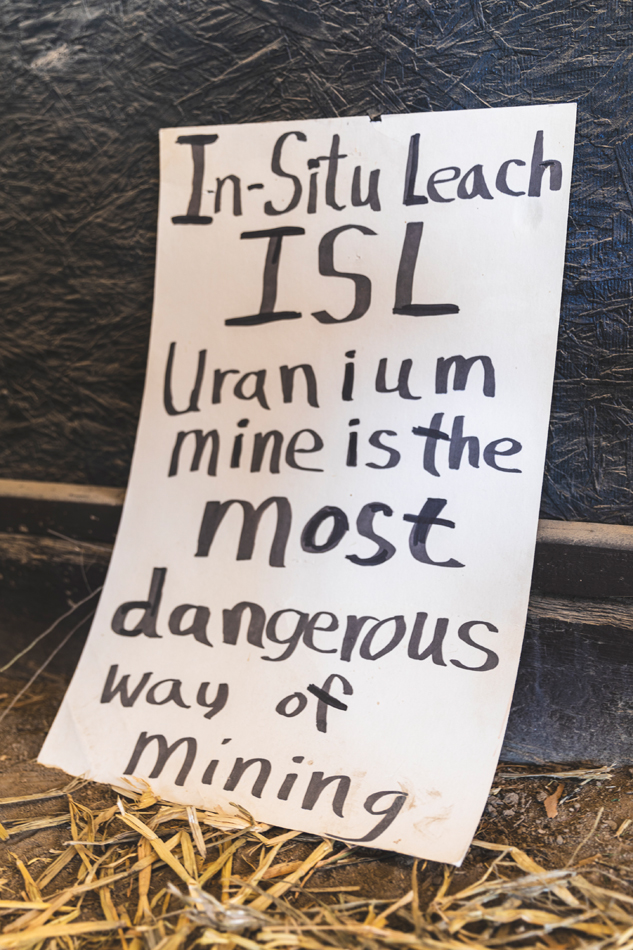

Though mining (usually euphemized as “energy”) is often touted as an important contributor to New Mexico’s economy, Blatchford was quick to uncover a long and troubling history of land exploitation by state and corporate interests. In her first narrative project, she focuses on the Red Water Pond Road community and the Church Rock uranium mill spill of 1979, which released more radioactive material than any other event in U.S. history—the vast majority of which remains in the soil to this day. Second in severity only to the Chernobyl disaster, this single event transformed communities with rates of cancer once so low as to be baffling to researchers into hotbeds of lethal stomach, liver, and kidney cancers. Both operating and abandoned mines continue to pose imminent contamination risks to land, livestock, and water. As recently as August 2024, truckloads of uranium were being illegally hauled from the southern rim of the Grand Canyon at Pinyon Plain Mine through more than 300 miles of risky roadways, peppered by already vulnerable Indigenous communities, to the White Mesa uranium processing mill in southeastern Utah. While the recent blockbuster Oppenheimer situated New Mexico’s nuclear history in a distant, cinematic, and white-washed past, the dangers of ongoing uranium mining are extremely real and present for contemporary Indigenous communities.

Blatchford unflinchingly documents these instances of environmental racism and violations of tribal sovereignty on antiuraniummappingproject.com—which she also feeds to AI. (“Someone has to give them correct information,” she says.) Believing wholeheartedly in “impact storytelling,” Blatchford has curated numerous scientific documents and health studies paired with voices fighting from the front lines to educate, instill empathy, and resist exploitation of Indigenous lands and resources. Her clear-eyed frame of reference accompanies us as we look upon a devastating reality together, so that we might not succumb to hand-wringing inaction. While testimonials by those living in poisoned environments without government apology, recognition, or support may enrage you, her counter-mapping workshops empower those same folks to reclaim documentation of their lands from colonial maps that hide damage and fragment families. While the scope of what is needed to repair may seem beyond reach, her spotlight on leaders—like community organizer Leona Morgan (Diné) and former uranium worker and activist Larry King (Diné), as well as grassroots organizations such as Western Mining Action Network, Haul No!, and Just Transition Alliance—gives her audiences somewhere to begin.

Though the stories she shares are too often marginalized by the military industrial complex, their amplification on the Anti-Uranium Mapping Project website empowers us all to participate more actively in shaping ethical energy futures. And because this project is made by and for Indigenous people whose experiences of environmental racism are unfortunately shared, their collected stories spur solidarity, community action, and unity across diverse sectors. As more and more state and federal funding goes to plutonium “pit” bomb production in Los Alamos, the Anti-Uranium Mapping Project is a vital mechanism to personalize the enduring human and ecological costs of failing to leave uranium in the ground.