Tucson-based artist Anh-Thuy Nguyen declares “rice is mother” in her current solo exhibition. At her studio, a visit begins with a meal.

The fragrant aroma of lemongrass permeated artist Anh-Thuy Nguyen’s home one late December day, as I arrived for a studio visit that took the form of a mindfully prepared and slowly savored meal featuring jasmine rice and soup made with pork, tofu, and vegetables including a plump yellow squash I watched the artist pluck from her backyard garden.

“My practice is embedded in my way of living,” Nguyen explained as she welcomed me to her home in Tucson, where she had me don a pair of straw sandals just inside the front door before taking me through the spaces where she brings her creative vision to life—including the garage-turned-studio filled with books, vintage photos, eclectic objects, and various works in progress.

Trays with photographs, including several from her Thuy & project exploring female immigrant experiences, lay atop the dining room table where we’d eventually linger over food served in mostly student-made ceramic vessels I’d observed Nguyen thoughtfully choosing with an apparent eye to their aesthetics, functionality, and relationships to one another.

Food is central to Nguyen’s practice both conceptually and as an art medium. “There’s no way for me to feel home again other than food,” she says, referencing associations between food and family and the ways U.S. immigration policies make it difficult to travel back to Vietnam, where she was born and raised.

“Rice seems very insignificant,” Nguyen told me as she used chopsticks to move bits of garlic-seasoned pork into her rice bowl during lunch. “A single grain seems to have no value, but when you have a lot of rice, it fills you up and nurtures you.”

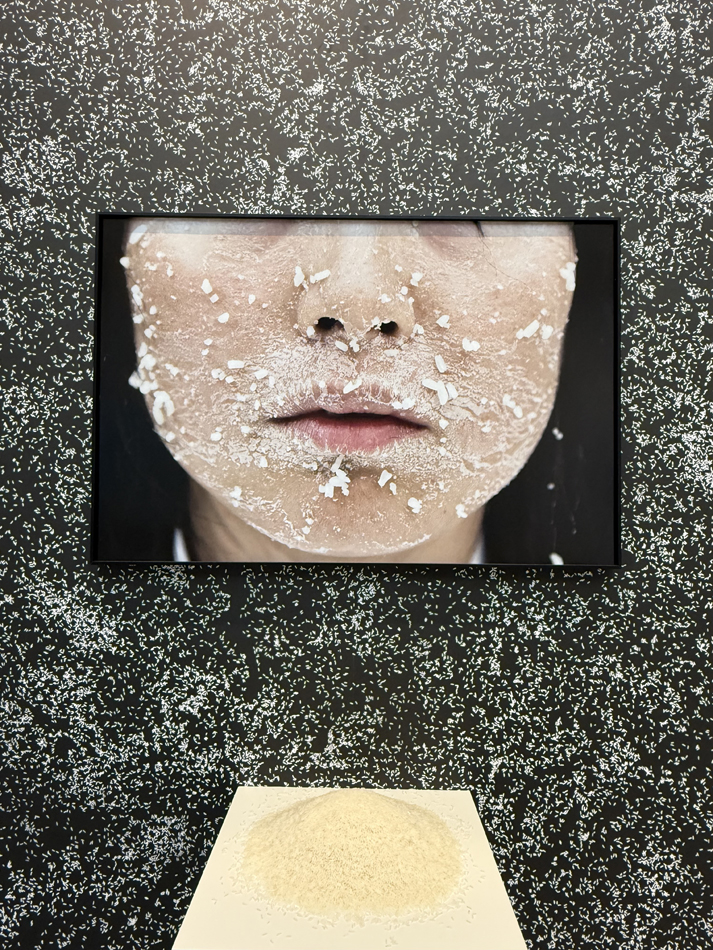

The grain is central to her Rice is Mẹ (“rice is mother”) exhibition in Chandler, which illuminates the ways rice undergirds Nguyen’s identity. “Rice makes me the person I am,” she says. “Working with rice is part of embracing my hybridity.”

Works on view include seven ceramic grains of rice set atop a small bronze cast of her lower jaw and tongue, three clear glass forms of her own head filled with thousands of grains of jasmine rice, and a video featuring long, meticulously strung strands of rice-shaped beads that reference her mother’s gray hair and the wisdom passed between generations.

“The ideas come first, then I think of the medium that will work best,” says Nguyen. “If it’s photography, then I pull out my camera and set it up in the garage and play with it. If I need to use another medium, like ceramics or glass, I learn it by taking a class or teaching myself.”

My work is slow and filled with hidden symbolic meaning.

“Next semester, I may work with screenprinting with ceramics or macrame with porcelain,” she says. Hybridized handwork like this can be time-intensive—time she marks, in part, by her academic calendar as the photography department head at Pima Community College. “I have these processes I can play with—all I need is time.”

Lately she’s been building a body of work that centers on the dangers of some chemicals used in nail salons, thinking about the history of women refugees from Vietnam creating or working in salons and data showing the health risks of exposure, including miscarriage.

I noticed a V-shaped neon sign that reads “vietNAIL” while grazing on pistachios, dried jackfruit, and other snacks in small ceramic bowls lined up on the kitchen counter.

It’s part of an interactive art experience Nguyen presented in 2024 in a small rented space in Tucson, where she ran a performative nail polish bar. Early on, she funded the project with a Night Bloom grant from The Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson.

“I decorated the shop with a visual design based on data about the toxicity of various chemicals,” she recalls. Similarly, Nguyen used information from the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration website to create ambient sound for the installation.

Nguyen hopes to incorporate other elements over time, including an art piece taking the form of a mobile vehicle she can take to beauty conventions and other sites. “I’m really doing this project to raise awareness,” she says. “I like to use playfulness in order to discuss serious situations in a gentle way.”

Moving forward, Nguyen plans to examine histories of forced migration. “I am investigating the relationship between rice and migration through the history of Vietnam with foreign actors like France,” she explains.

With each body of work, Nguyen layers story upon story, exuding a deep intentionality that mirrors the way she prepared and served the meal we shared before she sent me off with slices of savory squash beautifully wrapped up like a work of folded-paper art.

Their delicate scent filled my car as I made the drive back to Phoenix, recalling words Nguyen shared with me during our visit. “My work is slow,” she told me, “and filled with hidden symbolic meaning.”

Nguyen will appear with artist Safwat Saleem for Our Stories: The Highs and Lows of Raising a First-Generation Child, a discussion at Chandler Museum on Saturday, January 24 from 10:30 am to 12 pm.