Andrew Ina’s multi-media artwork delves into diasporic memory and displacement, using his family’s photographs documenting their lives in Lebanon and the United States.

Lubbock, Texas | andrewina.com | @andrew__ina

“History—it depends who you talk to,” says Andrew Ina, whose recent work delves into his family’s archive, oral histories, and his own memories to reflect a history of migration, fracture, and longing.

The son of Lebanese migrants who fled a country mired in civil war, Ina largely grew up in Cleveland, Ohio, feeling in between cultures, not quite belonging to either. He now lives in Lubbock, Texas, with his family, where he teaches at the School of Art at Texas Tech University.

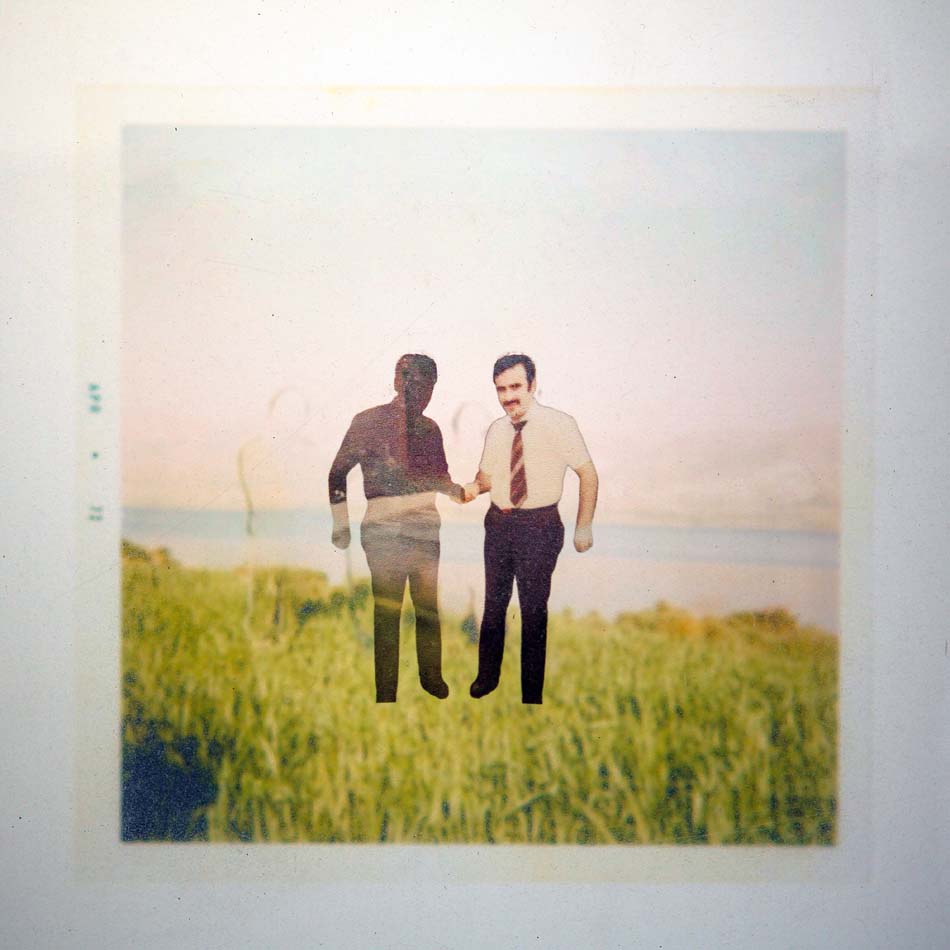

How Often Have You Sailed in My Dreams (2023) is a soundscape with a two-channel video projected onto surfaces that jut out at perpendicular angles from the wall, architectural fragments that are “of the space, but they don’t quite belong to the space.” Family photographs—of his father before and after moving to the U.S., of his first visit to Lebanon as a child—flash and move across the vertical surface, while on the horizontal plane, a projection of water remains a constant.

On the opposite side of the vertical panel, situated above the sea, Ina has affixed a floral wallpaper—a motif that recurs in his work—a replica of the wallpaper found in the kitchen of his childhood home, representing the “idea of domesticated, ’90s, middle-class comfort, where we found ourselves growing up in Cleveland.” It’s a representation of nature with no connection to the land, divorced from anything real, but for the artist’s own memories.

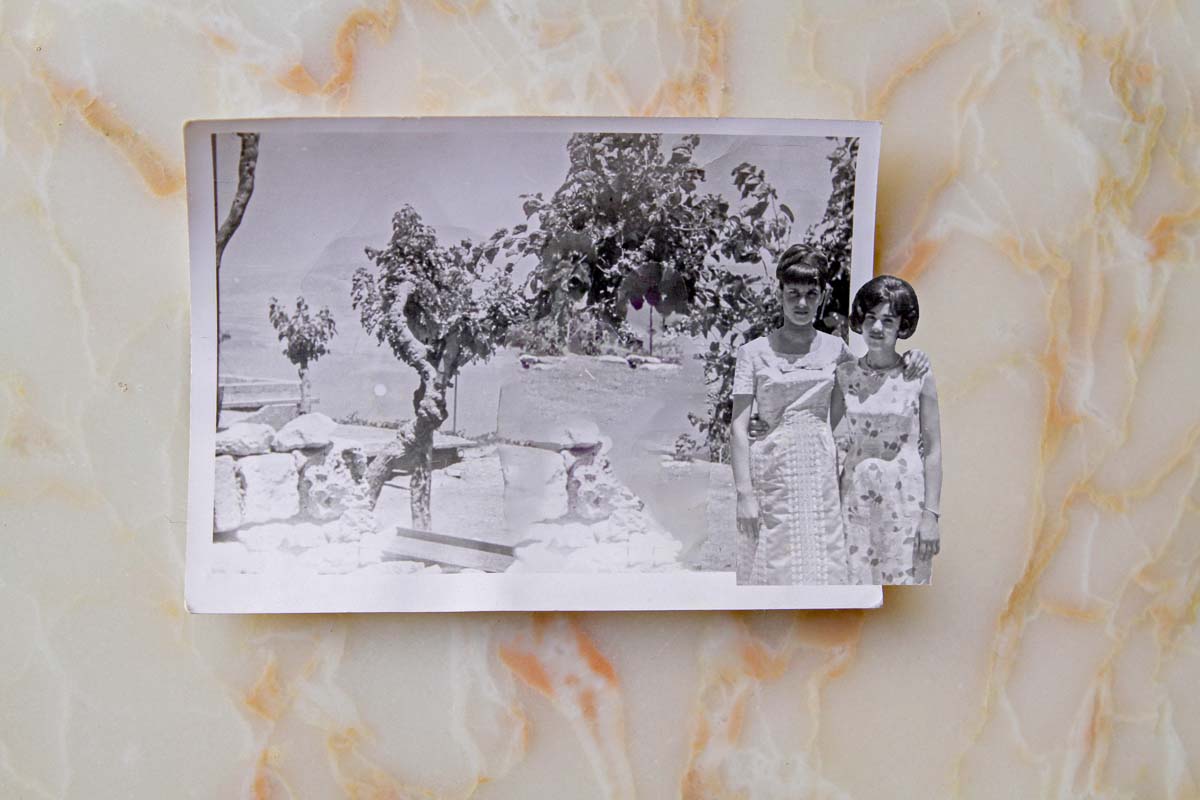

Acts of displacement occur frequently in Ina’s work, in the translation from physical to digital media, in the excising of the figure from the ground. In What If You Had Stayed (2023), the figures of Ina’s two aunts—one moved to the U.S., the other stayed behind—appear and disappear in a two-channel video projection-mapped onto a free-standing cut-out of their silhouettes and on a panel emerging from the wall. The viewer cannot view both projections simultaneously, but must navigate between perspectives.

In these works, Ina poses a question that is faced by many in diasporic communities, caught between the land that was left behind and a vastly different life in a new place. Ina often wonders about how culture constructs memory. “Where does a biological memory leave off and a narrative begin?” he questions. Can you tell a story over and over until it’s true?