“This place. The river is life,” Luke Carr tells me as we walk through a stand of cottonwood trees near the flowing water. He lives on a small farm in a remote part of northern New Mexico, next to the confluence of two rivers. For a musician, this place provides silence for writing and recording, and after a few years of collaborating and touring, Carr appears very happy with this opportunity to meditate on the landscape and process loose ends.

Carr recently disappeared from the forefront of the Santa Fe music scene into an isolated home studio to work on an incomplete solo album. Last summer, the critics and promoters in town were all throwing their support behind his band Storming the Beaches with Logos in Hand. The group, headed by Luke Carr and Caitlin Brothers, performed with adept musicianship, flawless vocal harmony, passionate lyricism, and fearlessly experimental compositions. A narrative element added to their mystique. Each album and performance contributed to a Silmarillion-like mythology. The result was a fresh, theatrical indie band with surprises up its sleeves. I wasn’t alone in thinking that STBWLIH was poised for popular success. The town was seized by a now familiar excitement that it might soon produce another group like Beirut that Santa Fe could claim as its own. And with so much good will behind the project, I was naturally surprised to hear that Carr is taking a hiatus from Storming the Beaches to work on other projects.

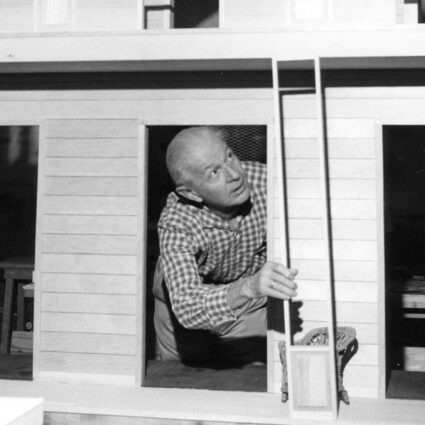

Carr has spent the last several months behind a mixing console. Unlike performance, the studio offers a chance to make mistakes and hone his craft as a songwriter. “On a movie set, they can shoot a scene seventeen times. The actor has the chance do each take differently,” he tells me.

“Right now, I’m experimenting. I’m saying, ‘Let’s try this and turn the gain down and move the mic closer.’ The lyrics are still changing based on things that are happening. That’s why the Beatles were great. They weren’t performing. They were experimenting with this piano or this microphone.” For Carr, songwriting and recording are part of the same creative process, one that he likens to filmmaking constantly.

The new record—provisionally entitled Have Had—will be Carr’s second solo album. He started recording many of the songs before Storming the Beaches consumed his attention for most of the preceding year. They have a more conversational character. This record is more personal. The songs are shorter and “poppier.” Carr is engineering the album himself and plays most of the instruments. Some of the parts are played by Nathan Smerage, who is also composing arrangements for strings. He is especially excited about that last fact. “I’ve been dreaming about having strings for so long… Nate is an incredibly talented musician. I really enjoy collaborating with him.”

Carr intends to make Have Had more accessible than the intentionally abstruse aesthetic of Storming the Beaches, which he describes as a “world building project” rather than a band.

The solo work explores his personal emotions and relationships in a real-world, “journalistic” context, rather than the elaborate costuming of Storming the Beaches, where Carr himself isn’t necessarily a character. “The two worlds are both very alive to me and conscious of each other,” he tells me. “This album discusses a lot of mysticism and spirituality that also appear in the world of Storming the Beaches.”

It’s very quiet where Carr lives. We meet at an empty diner on the side of the highway, a long drive from Santa Fe. The waiter sits at a table, eating, and gets up slowly when somebody comes in. It’s very relaxing being here. He tells me about this tiny village’s violent history; it’s very dramatic for such a subdued place. There is a famous picture of the surrounding landscape by Ansel Adams hanging on the wall over the table. With a practiced storyteller sitting across from me, it doesn’t take long to feel the presence of the past.

The structure that serves as Carr’s home and studio overlooks an orchard, a greenhouse, and a pasture filled with cattle. There are several other houses on the property and a stunning view of distant mountain peaks. In the soundproofed recording room, everything is organized neatly: cables coiled on hooks, instruments in cases. Carr turns on a computer and plays an incomplete song from the new record over a set of monitors. He adjusts the levels to point out different parts of the mix. The vocals float over a dense arrangement of guitars, drums, and processed percussion. The result is moody, mysterious, and simultaneously danceable.

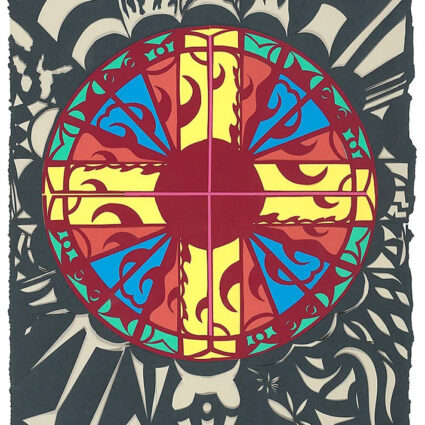

When work resumes with Storming the Beaches, it might take many forms. Unlike the controlled environment around Carr’s solo work, STBWLIH is a highly collaborative project, and the musical personnel have changed often over the years. When I saw their show at Currents New Media Festival 2017, promoting their last album Bailiwick, Refused, the group boasted eleven musicians on stage, including a costumed ensemble of percussionists, plus a five-person crew running lights, sound, and video. Shortly afterwards, the group toured as a two-piece. The protean nature of the lineup feels appropriate, because the real core of Storming the Beaches isn’t the music. Ultimately, the band’s two records are storytelling devices that present pieces of the overarching story and draw on the same expanding source material. Future productions will benefit from beginning in the same primordial ooze.

The narrative behind Storming the Beaches tells an alternate history of the colonization of North America. All of manifest destiny is confined to a region called New Europe in what we know as Central America. The settlers have turned the conquered part of the continent into a post-industrial wasteland crisscrossed by oil pipelines and plagued by political factionalism. To their north, the indigenous people of the Northern Grace (in approximately the same place as the U.S.A.) have successfully repelled attempts at invasion. Their lands are the only source of clean drinking water for the colonists. In Southwick, the capital of New Europe, legends have begun to circulate about the existence of magic in the Northern Grace. There has been no contact between the two civilizations for many years. Bailiwick, Refused tells the story of Dessa, a woman from a political dynasty in Southwick who leaves home to become a resistance fighter.

It’s almost overwhelming to hear Carr lay out the expansive storyline behind the previous albums. He has big ambitions for what lies ahead. “In some respects, it’s like I’m starting production on a motion picture, but preproduction has taken years… I’m imagining a lot of things, but it’s unclear what the next step is.” In addition to film, Carr mentions the possibility of adapting Storming the Beaches into live theater or novel form.

Have Had will be an appropriate companion to Carr’s other work, condensing many of the same themes into listenable hooks. Bailiwick, Refused was written in such a way that none of the songs is suitable for the radio. “A lot of people are in a hurry and don’t have time for a story,” Luke says. “The radio wants songs that are under four minutes.” None of the material in the Storming the Beaches repertoire fits into such unforgiving parameters, but the songs on Have Had do, and Carr wants his solo work to succeed in a conventional music market. For Storming the Beaches, he plans to develop an entirely different business strategy. “Maybe more of a non-profit model,” he says, musing on the various ways he could collaborate with more writers and performers.

“I used to think of stories as something from the past,” he says as we come upon a pair of coyotes picking at the carcass of a dead cow. “They’re not. People are living in stories. They’re active.”

After listening to the unfinished tracks from the new album, we take a walk down to the river, getting a feel for the land. Luke speaks reverently about this place and about the West in general. He grew up visiting New Mexico and hearing stories from members of his family who were completely entranced with the desert. He sympathizes with Christian Bale’s character in Newsies. “My sisters and I used to watch that movie, like, three times a week,” he confesses. The boy in the movie is named Jack Kelly, but everyone calls him “Cowboy.” He lies about his parents’ connection to the West in order to justify a dream of moving to Santa Fe. “Seven out of ten photos of me as a kid, I was dressed like a cowboy,” Carr says. “In Pennsylvania.” It’s a familiar story of people moving here from the East. The mystique of Santa Fe has developed such a life of its own that many people can’t distinguish the mythology from the reality when they arrive.

Keenly aware of the power of stories to shape a place, Carr notes that popular myths often have unexpected effects on the places where they originate. “If you advertise an aspect of a place, the wilderness for example, you’re changing the wilderness by bringing people to it. Santa Fe is changing. It’s growing every day.” Carr says that Santa Fe has gotten “too big” for him. People romanced by its small-town aesthetics have turned it into a sizable city. The story of the place is at odds with its reality.

Carr is very careful when describing his present home. He asks that I not disclose where he lives. “I feel there’s so much awareness and sensitivity not being from here,” he says. He is cautious about what he advertises. I wonder if he can truly leave no trace in the history of this place. “I’m like the Ansel Adams photo in the restaurant,” he says, laughing, referencing another artist whose legacy created a lasting image of this town.

“I used to think of stories as something from the past,” he says as we come upon a pair of coyotes picking at the carcass of a dead cow. “They’re not. People are living in stories. They’re active.” He sees art as an inherently political activity and hopes to be on the right side of history. “The effort to rewrite your personal stories is a rebellion,” he says.

During a tour in late 2016, Carr visited the Standing Rock protests in North Dakota. After spending the preceding years conceiving a fictional world of pipelines, scarce water, resistance movements, and Indigenous wisdom, the experience made him feel that STBWLIH was on the right track. “Part of the experience was a confirmation,” he says, “actual proof that the story of Storming the Beaches is worthwhile. In a sense, I am more clear now that my imagination has its finger on the pulse of a greater collective unconscious, both in this reality and otherwise, both in past and future.” Hearing him talk about Standing Rock, I realize that Luke’s ideal conception of his band is organized like a revolutionary movement: loosely affiliated, ideologically malleable, radically inclusive, and fiercely humanitarian. “The power present at Standing Rock was immense,” he says, “which was contributed by so many individuals, each bringing their own story, skills, intentions, and each having their own experience.” He describes Storming the Beaches in almost identical terms.

Carr tells me about a picture he took of a water protector meditating at Standing Rock. When I ask if we can print it with the article, he declines. “Whatever he was doing was so much more powerful than a photo ever could be.” Carr’s work has this quality. What is seen and heard merely suggests something more powerful dwelling in the spirit world.