In two successive solo exhibitions, Taiwanese artist Lu Wei traces a wild pilgrimage through the shadows of motherhood into the searing heat of the Utah desert landscape.

Lu Wei: Entering Into The Serpent

May 2–July 13, 2025

Ogden Contemporary Arts

One of the oldest and most important myths from Mesopotamia tells of Ishtar’s descent into the underworld, where she arrives naked to be judged and killed, her corpse hung on a hook. After three days and nights, she resurrects and returns to the living world.

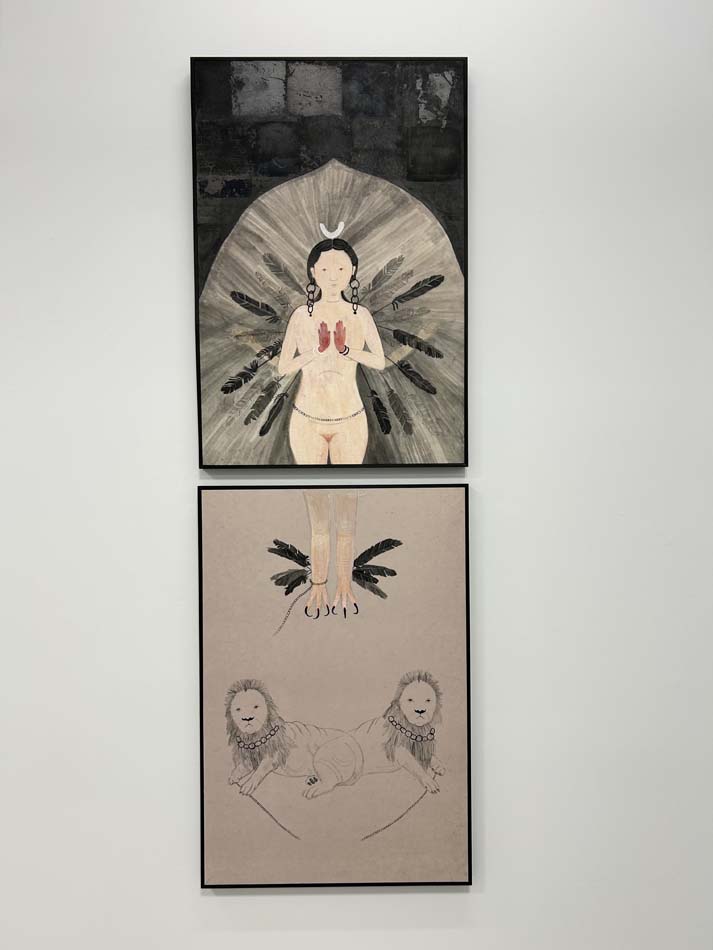

In Taiwanese artist Lu Wei’s recent exhibition Ink Shadows, at Material in Salt Lake City, the artist depicted Ishtar’s triumphant return in Queen of the Night (2024). In the painting, Ishtar’s hands are stained with blood. She’s no longer innocent and unconscious to pain and brutality, but now stands radiant in an aura of feathers sprouting from her spine and ankles. There are two lions, universal symbols of strength and courage, harnessed and lying down beneath her. We see that her feet have been transformed into talons. Ishtar is fully present, gazing directly into her viewer’s eyes, and hybridized with the freedom and skills of a raptor, a carnivorous bird that hunts with its feet. Ishtar will never hang defenseless like a piece of meat on a hook again.

Bleeding and birthing, destruction and death, renewal and creation: across cultures and times, these images signify the feminine power to give and take away life. Invoking a multitude of feminine archetypes, Lu’s recent works, exhibited in two successive solo exhibitions curated by Material in Utah, depict fierce goddesses and devouring mothers in all their dark and wild fury.

Lu’s recent works depict fierce goddesses and devouring mothers in all their dark and wild fury.

In her exhibition Entering Into The Serpent, which remains on view at Ogden Contemporary Arts until July 13, the viewer is first struck by the undeniable raw grace and wild beauty emanating from her imagery. The artist’s expertise garnered from her years of studying classical Chinese ink painting, a rigorous training that included calligraphy and poetry, is clearly evident in her large-scale ink paintings and scrolls. Looking closer, one encounters in them a deeper perspective on the stories that have often served to demonize women, alchemically transmuting the projections of dark chaos to reveal the profound freedom and sovereignty that comes through the refusal to conform or be contained, no matter what the cost.

In 2024, Lu was awarded a grant from the Taiwanese National Culture and Arts Foundation to embark on a five-month-long curatorial project in Utah, culminating in exhibitions around the state and acquisitions of her work by the Utah Museum of Fine Arts.

The artist recalls during our interview at Material, “In creating my two solo shows, I decided that one is more about the shadow, while the other one is about the serpent, and the relationship between the woman and the land in different places.”

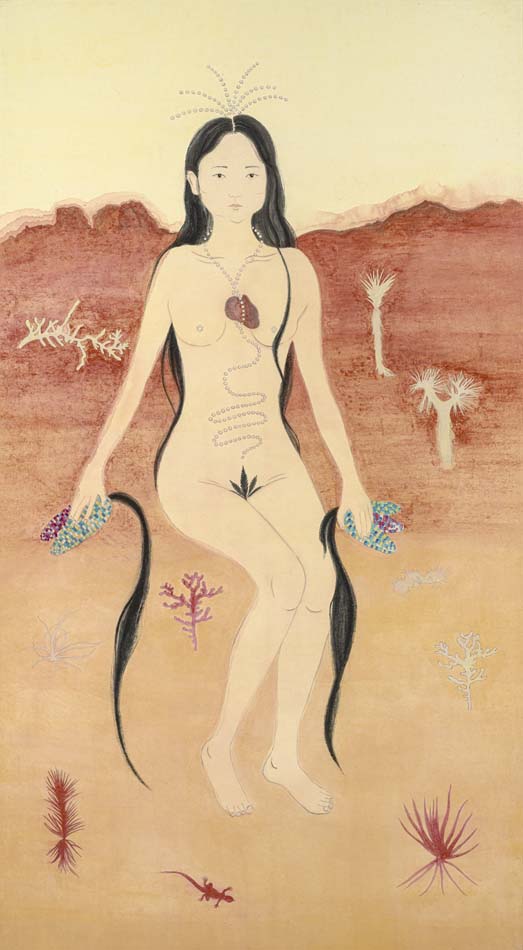

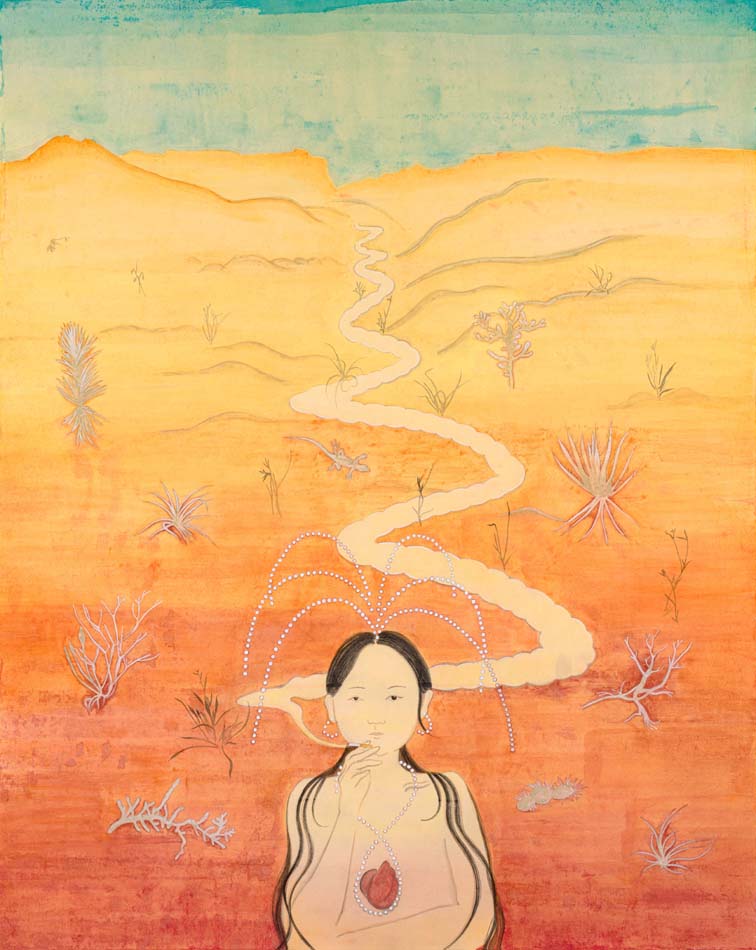

The Utah landscape, so often imagined as barren or inhospitable, is reimagined in her work as a living feminine terrain, ripe with wisdom and spirit. Lu’s works don’t romanticize the desert, they animate it as a space of resistance, purification, and ancestral power. Inspired by Gloria Anzaldúa’s essays and poems in Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, Lu’s recent travels in the American Southwest and Mexico introduced her to the enduring Native American and Mesoamerican feminine archetypes. At OCA, the devouring force of the Aztec goddess Coatlicue appears in Dance with Serpent (2025), along with the divine nourishment of Corn Mother (2024), who feeds the world with her body. Desert Goddess (2024) depicts a woman with a cigarette between her lips, exhaling smoke that spirals behind her into a desert landscape. The smoke becomes a path that guides her through the desert, reclaiming a forgotten spiritual lineage that resonates beyond the limits of human and ethnic identity.

Lu shares, “When I visited the desert in this country, [I found that] the colors are very different, like golden colors, and it changes every time depending on the sunshine. And there’s also dirt colors—earthy.” She describes the feeling of her body traveling from the humid, tropical air she knew to an extremely dry environment “that also changed my paintings from a more watery texture to sand.”

Sky, Earth, and Underground (2025), a monumental scroll that hangs like a veil from the main wall of the gallery, invites viewers into a mythic world where the wild feminine rises, coils, births, and reclaims. Here, we witness a mother’s descent from her open and vulnerable heart into the underworld while simultaneously birthing a child.

The artist is at her fiercest when dismantling outdated and idealistic expressions of feminine devotion.

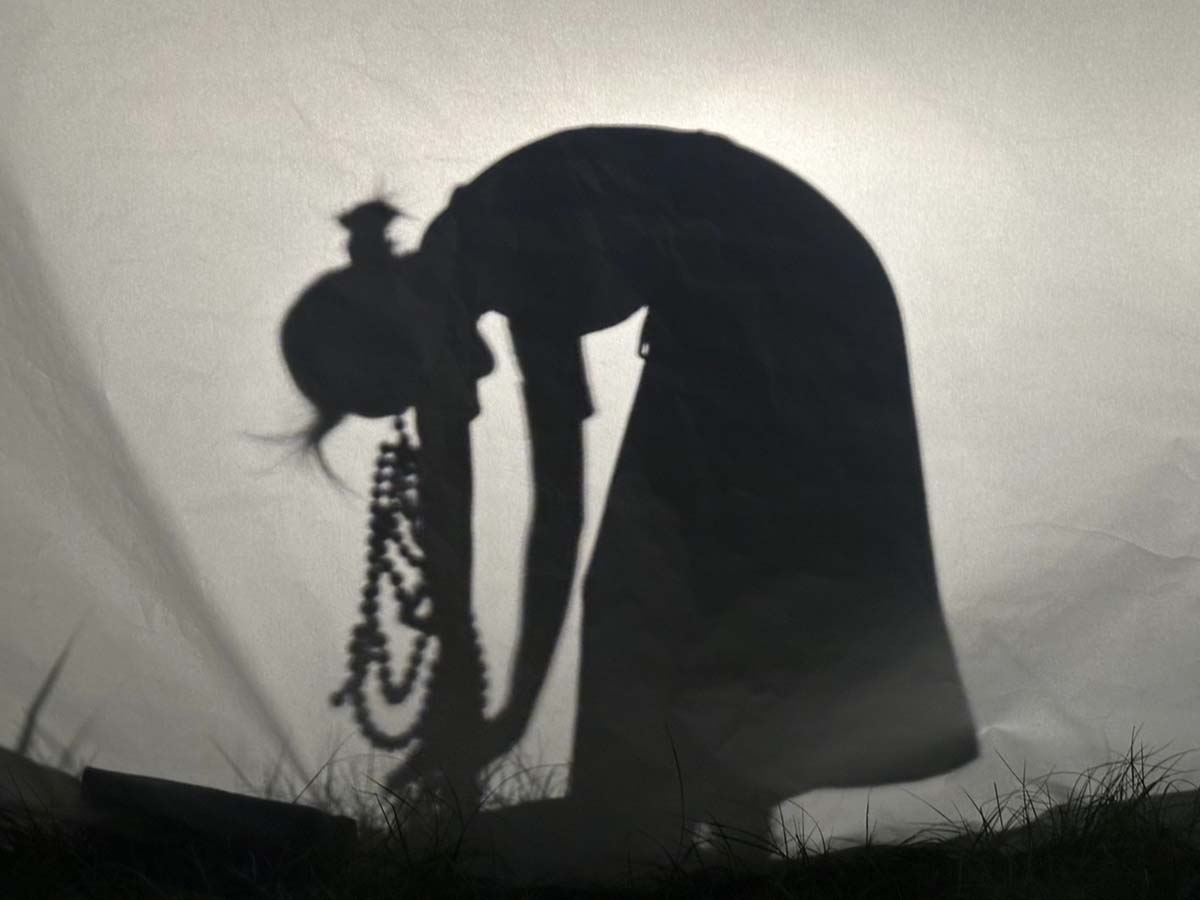

At the heart of Entering Into The Serpent, however, is a commanding three-channel video installation. Inspired and named after a poem she wrote as a young mother, Mirrors (2025) melds shadow play, performance, and matriarchal lineages to explore transformation through the female body and motherhood. On one screen, we witness Lu’s son engaged in a gentle shadow play, his silhouette flickering and merging with the mother figure, evoking the porous psychic membrane between mother and child that’s filled with light and laughter. The second screen features a woman dancing slowly through a forest, entering a womb space, moving through different phases of life, some happy, some difficult. Her body is adorned in strands of heavy pearls constructed to resemble a rib cage. She moves as though she is shedding her skin in a uniquely female journey of joy, ancestral pressure, duty, and sorrow ultimately unbound by her wild natural instincts. The third screen zooms in on Lu’s hands and the movement of brush and ink, her most solitary and precise artistic expression. Together, the three channels offer a layered, intimate meditation on creation and dissolution, on artmaking and mothering as parallel acts of devotion and confrontation.

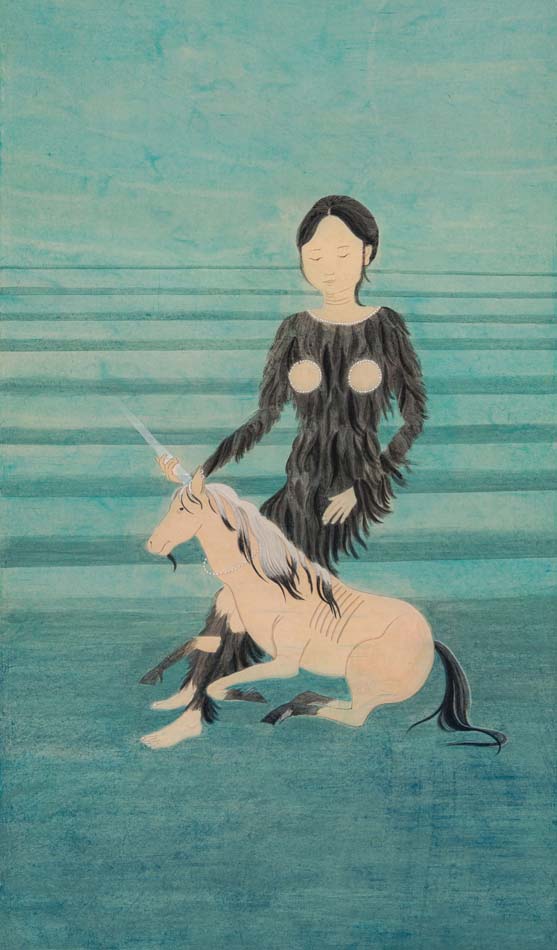

The artist is at her fiercest when dismantling outdated and idealistic expressions of feminine devotion. At Material Gallery, Wild Woman (2024) refers to Lu’s fascination with the iconography of unicorn tapestries from the late medieval period, showing wild unicorns captured and domesticated, representing female purity and control. But in Lu’s interpretation, a bare-breasted woman draped in fur like a wild horse’s mane is intertwined with the unicorn who leans into her body. The woman grips the animal’s magical horn at its root like a phallus. This creative life force is not to be domesticated, but directed and embodied, and if it must be contained in any way, it will be on its own terms, through art, clarity, and choice.

Lu’s illumination of the shadow mother reaches its most defiant note in her own embodiment as artist. Her work does not plead for understanding. She is wild, visionary, and precise. And she is bound by motherhood, not despite her art, not as a martyr to it, but as a force strengthened by it. In Entering Into The Serpent, Lu asserts that motherhood and artistic freedom are not mutually exclusive. They are, in fact, braided together like the serpents she paints as entangled, potent, and necessary.