In Memory presents the work of twenty-one artists who excavate the archives of remembrance to reveal how humans document, distort, and cling to the past.

In Memory

July 5, 2024 – February 22, 2025

Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, Salt Lake City

How does the human mind and heart process, document, and archive memories? In Memory, currently on view at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, presents the work of twenty-one artists who share insights on the various ways memory profoundly shapes identity.

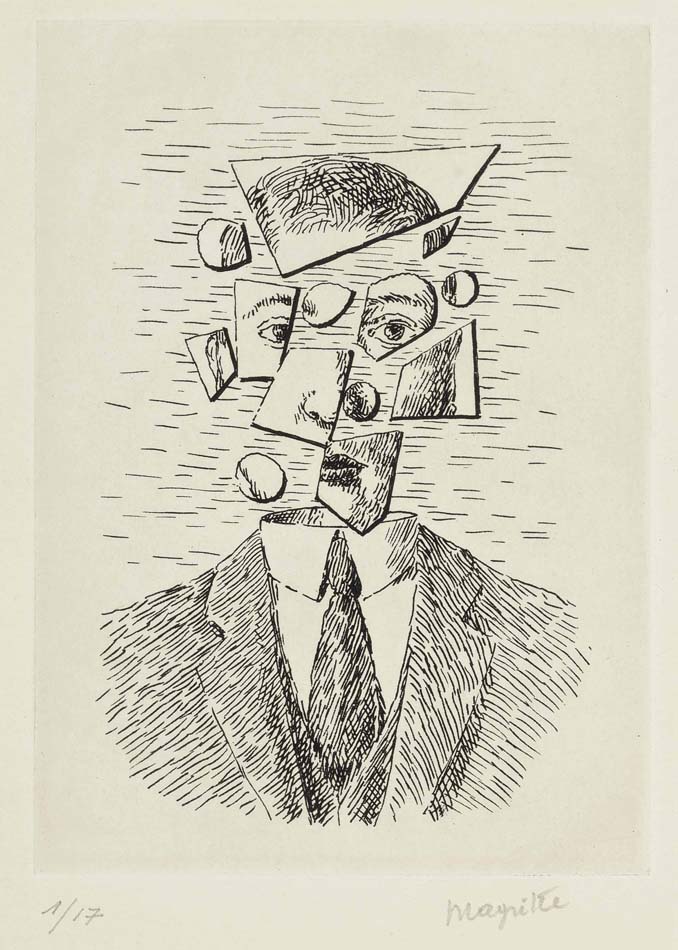

Upon entering the exhibition, a small etching by the Surrealist artist René Magritte, Aube á l’Antipode (1966), captures my attention. The image depicts the fragmentation and rupture of the self that can occur within the neural complexity of the brain due to trauma. The facial features in the portrait appear like a shattered mirror with dangerously sharp edges calmly floating above a seemingly well put together body in a business suit and tie. Using Surrealist techniques of displacement and unexpected juxtapositions, the artist evokes a sense of disorientation and anxiety, embodying trauma as a quiet persistent force, rather than an overt spectacle. The extended label refers to Bessel van der Kolk’s 2014 book The Body Keeps the Score noting that while the human mind may disassociate or simply forget any event from the past, painful or pleasant, the body and the senses are meticulously imprinted by the physical sensations that occurred simultaneously. Emotions can be activated by certain smells, sounds, or images that will catapult us back, sometimes shockingly, into the inner archives of memory. It is these inner archives that the artists have chosen to bravely excavate, seeking deeper meaning below the surface of their human existence.

Earth-body artist Ana Mendieta recalls her primal connection to the land of her birth with her series Esculturas Rupestres (1981). Carving mythological goddess forms directly onto the limestone walls of the caves at Jaruco State Park, she evokes the ancient Indigenous legends and worldview of the Taíno people who were almost entirely extirpated by the Spanish conquest in 1511. In 1961, at the age of twelve, Mendieta was sent to live in the United States after her father joined anti-Castro counterrevolutionary forces in Cuba. She suffered from an almost unbearable trauma of having been ripped away from her home to be placed in an orphanage in Iowa, where she felt tragically disconnected from her living parents or anything remotely familiar. Tremendous healing occurred for the artist through her performance and site-specific works where she found solace and transcendence beyond the wounds of the past, re-establishing her place in the cosmos and her bond with the earth that she saw as a benevolent female entity that nourished and fully revived her spirit.

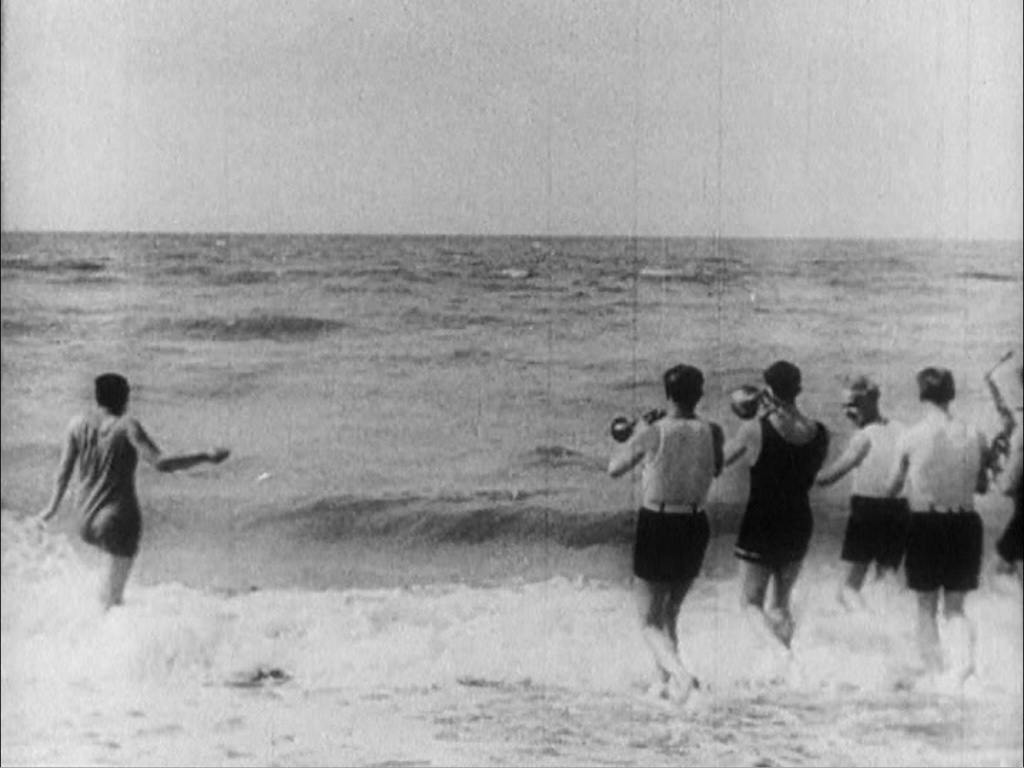

Helga Landauer Olshvang’s Diversions (2009) also recollects an irretrievable way of life disrupted by political conflict in archival footage of summer activities on the beach along the European coast in the 1930s. Carefree people roam from one delight to the next: laughing and playing in the sand, splashing in the water, renting boats, smoking and flirting in cafés. Particularly enjoyable to witness are the young men in formal suits on the sand, as well as pranksters on the beach in such modest swimwear and bathing caps, truly evoking a bygone era. Their playful diversions distract them from the reality that the war is coming and distract us as the viewers from our knowledge that life would never be the same for them again, and that they are long dead. The final frame of the film ominously states that the last scenes were filmed in late August of 1939. As we know, Nazi Germany invaded Poland in September of 1939, beginning World War II and all the devastating human suffering that came along with it.

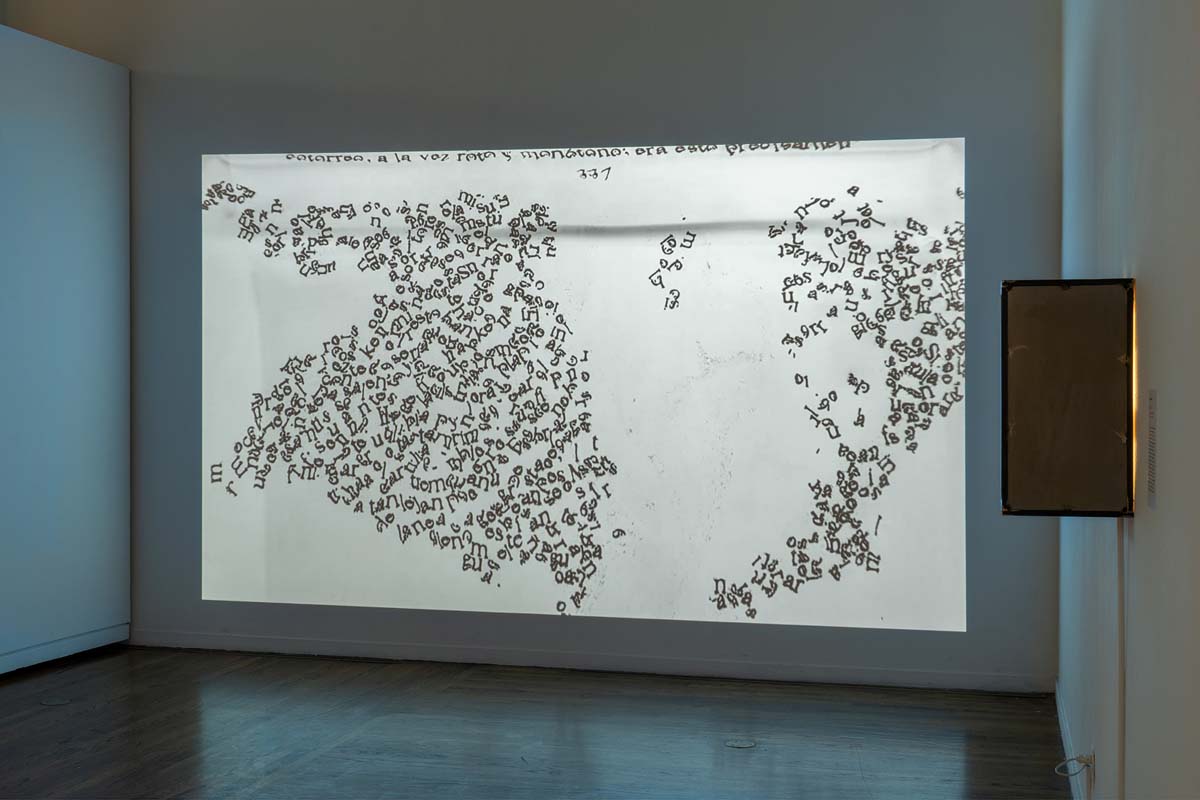

So how do we forget? How can we let go of the most painful events, so often simply out of our control, and carry on? Oscar Muñoz’s single-channel silent video Dystopia (2014) suggests that once our mind processes information or words on a page, those concepts and impressions are relentlessly dissolved into an ocean of consciousness that we may or may not choose to recall. The words in this work come from a Spanish translation of George Orwell’s 1949 dystopian novel 1984, a story famous for its detailed construction of a human reality marked by oppression. In the novel, the government-controlled Ministry of Truth rewrites or deletes contradictory histories that conflict with the elitist narratives used to indoctrinate citizens. In the video, pages of typed text dip into a liquid that lifts the letters, destroying our ability to read the signs of this totalitarian tendency, while at the same time freeing us from it. The charcoal letters detach and merge into a sea of blackness, diluted and dissolved into a comfortable forgetting of what could be.

The mind may choose to forget the possibility of such cruel realities, but the heart remains vigilant. In Dario Robleto’s The Heart’s Knowledge Will Decay (2014), the frequency of heartbeats recorded from different individuals over a period of three centuries are preciously collected and presented as scientific specimens on exquisite glass slides archived in a wooden box. Each individual pulse and heartbeat tracing no longer belongs to the human heart that once pumped blood through the veins of a human body. The elegantly depicted lines of the heart’s rhythm have become anonymous and all that remains to preserve and protect, yet it is the frequency of that heart, its tenderness of feeling and observation ever truthful, that lives on and always remembers.

Throughout the exhibition, each work of art casts light on the emotional and cognitive capacities of the human system to encode memory as we move through time and space in our daily life. These memories may not be our own entirely. The mind may also tap into the collective unconscious of global events such as war and political conflict, as well as archetypal forces genetically rooted in our ancestry. Acknowledging that the passage of time, along with the tremendous input of information our systems receive in modern life, can distort our perceptions, and that humans have a need to document and even cling to what has been, the artists reveal unique and often luminous ways of remembering through the stories of their own lives and chosen craft.