Perla Segovia, a Peruvian immigrant who has made Tucson her home for the past ten years, advocates for the value of immigrants through textile, embroidery, glass, and painting techniques.

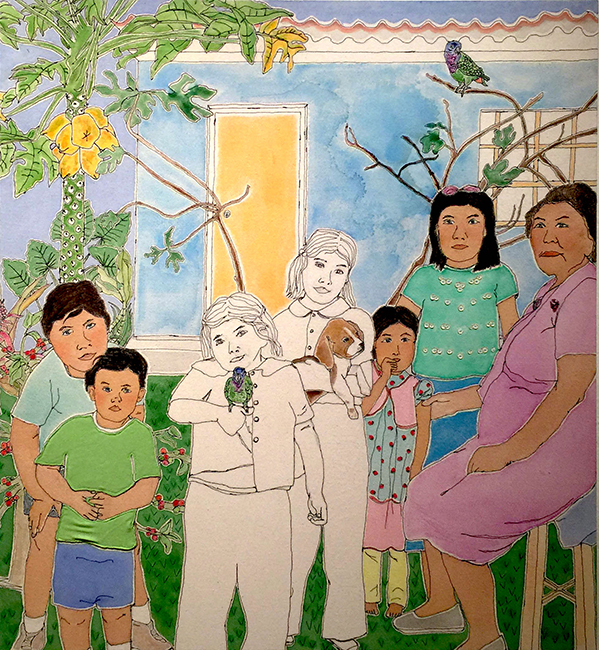

A painted family portrait anchors a dining room wall of Perla Segovia’s Tucson home. This particular work, brimming with inviting, eye-catching yellows, blues, pinks, and greens, depicts a group of seven posing in front of a tree-flanked home.

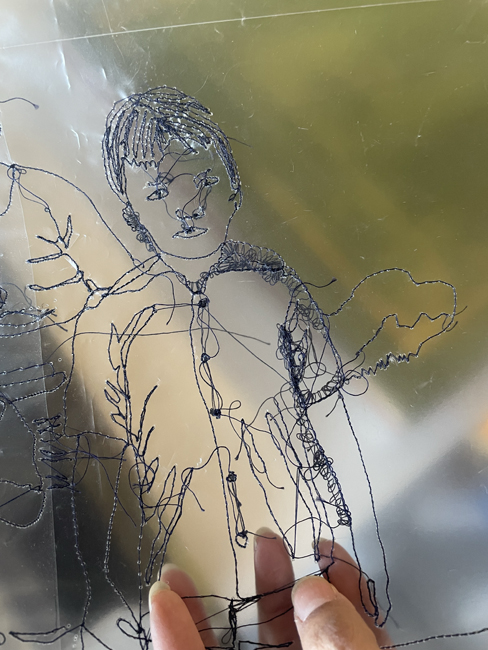

The two young girls in the composition’s center—Segovia clutches a bird, her sister holds a puppy—are absent of color. Instead, the sisters are outlined in embroidered dark-blue cotton thread.

The painting, which hangs above a piece of furniture displaying photos of Segovia’s family, seems unfinished. But it’s not. However, the mixed-media watercolor indeed portrays an absence in the artist’s life and other immigrants like herself.

“It’s about the precarity of memory,” says Segovia about the work that’s part of her ongoing series Immigrants’ Void. “The immigrants are colorless because they leave a void behind. I’m living that void now. My memories are living in precarity because I’ve lived more than half my life outside my home country, where I was born.”

“Making these paintings are a sense of [reclamation],” says Segovia, who has lived in many worldwide locations, including Tucson for the past ten years. “I’m still part of this place even though I have not lived there in so long. This place feels part of me and still belongs to me.”

“This place” refers to her home country of Peru, but it also hints at memories that become more and more tenuous the farther one travels from a memory. A large portion of Segovia’s multidisciplinary practice, which includes multi-layered mixed-media installations, is giving a compassionate, individualized definition to the immigrant to the United States, a marginalized group often pigeonholed as a monolith.

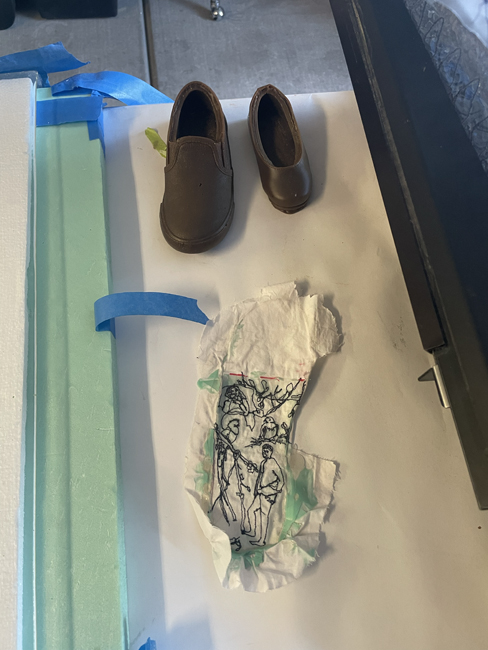

Though the subject matter is often heavy and heartbreaking, the work disarms and reels in the viewer, as when someone discovers that a gorgeous, handwoven child’s shoe featuring intricate embroidery—part of a gripping installation currently on view at the Tucson Museum of Art—honors children who have passed away in U.S. immigrant detention facilities.

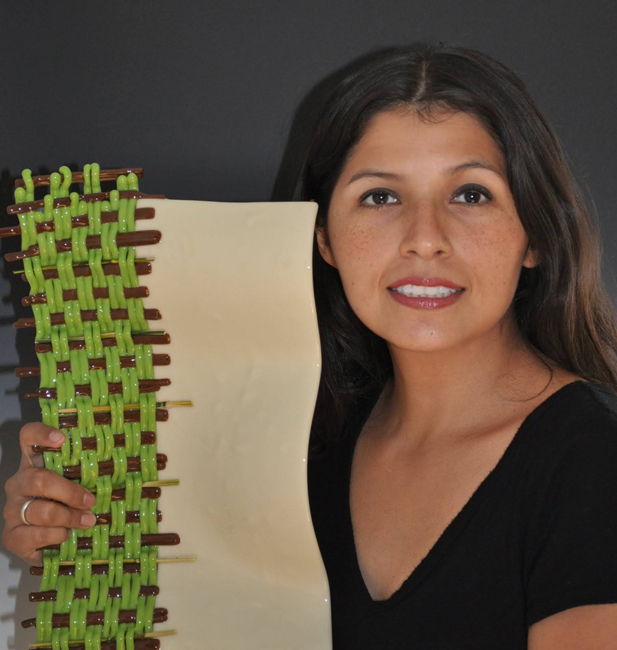

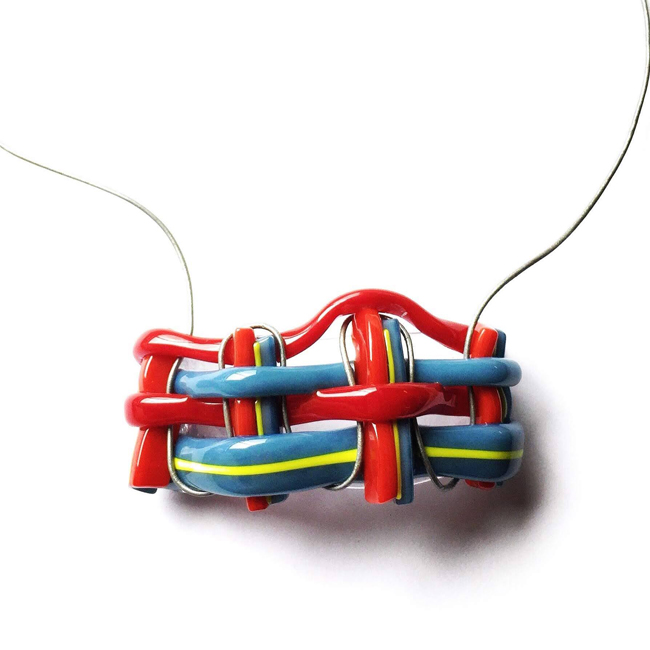

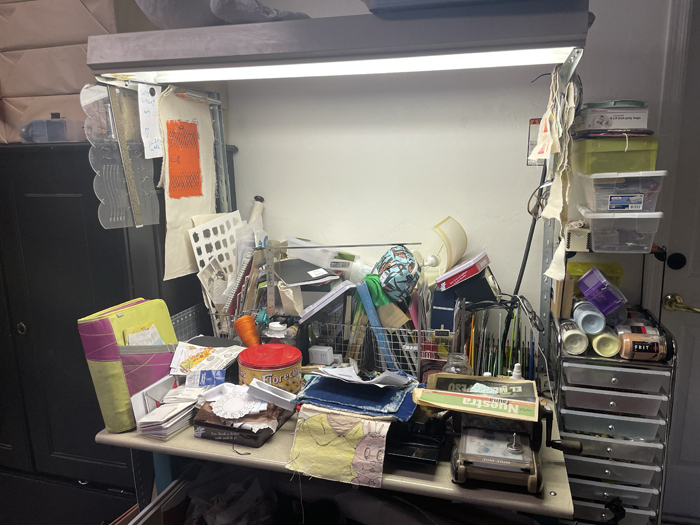

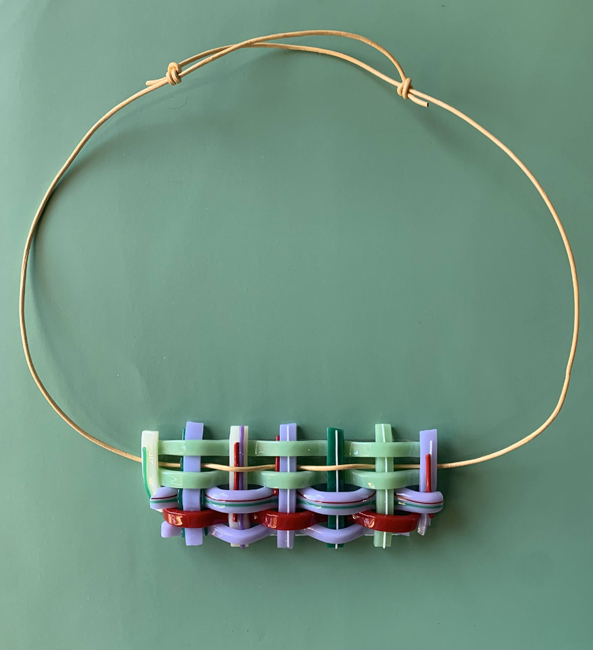

The personable, good-natured, and gracious artist is a maker through and through, whether she’s creating in her garage or at a kitchen table at the Tucson home Segovia shares with her husband, college-aged daughter, and teenage son. Her dizzying and laborious material process includes woven glass, glass casting, screen-printing, and embroidery on canvas and non-traditional media like plastic.

Born and raised in Peru, she grew up in places like big-city Lima and the small agricultural town Quillabamba in the Andes Mountains, the setting of the Immigrants’ Void watercolor hanging in Segovia’s home. When she was eleven, she and her family immigrated to rural North Carolina.

Segovia graduated with a bachelor of science in textile technology from North Carolina State University in Raleigh and then moved back to Peru to take a job as a handbag and shoe designer. After years away from her home country, she reconnected with her native culture while learning fused glass methods. She later moved to Italy and took a two-year course to become a certified modellista (patternmaker).

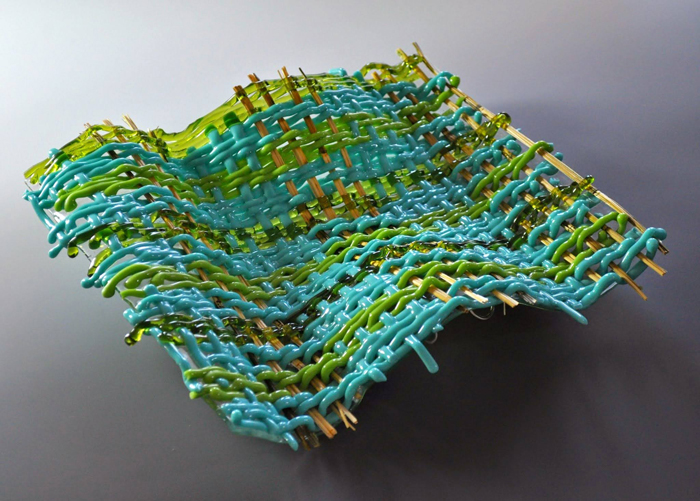

“I loved both glass and textiles. My main dilemma at that moment was, ‘How the heck do I work them together since they are so different?’ I started mixing and making weaves with glass. All of this is literally woven and then fused in a kiln.”

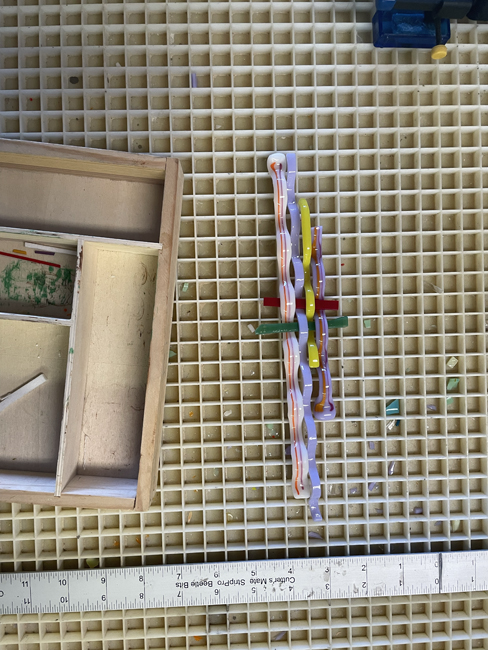

In Segovia’s garage studio, which has a clear view of the Santa Catalina Mountains, she shows me a series of woven and fused glass pieces, which employ traditional weaving methods that are transposed to sheet glass and then fired in a kiln. In addition to her fine art pieces, Segovia makes woven glass jewelry. Her garage studio is a laboratory that contains tubs of finished glass works, stretched canvases, burned and blank screens, shelves with art supplies and sketchbooks, and sheets of plastic embroidered with figures in her signature dark blue thread, which Segovia says represents the strenuous hope of immigrant children.

“I incorporate textiles and textile techniques into my work because they resonate with most of us and therefore have the potential to be an effective tool of communication,” says Segovia. “I believe textiles transcend culture, geography, and time and are capable of serving as a unifying impetus in our tumultuous society. They can connect people, engage with them, and motivate people to take action.

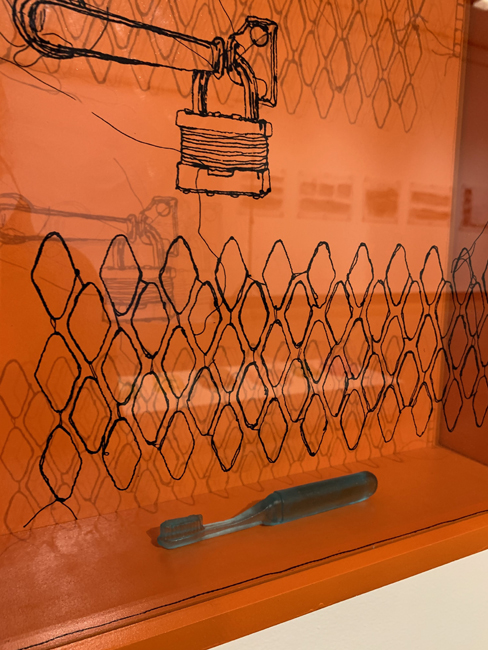

Segovia has experimented and pushed the boundaries of glass, coming up with a technique of screen-printing embroidery onto glass. One of these pieces, for example, is a painted family portrait featuring stitchwork that’s printed onto a delicate sheet of glass.

“I became attracted to glass because it can be shaped and formed like other sculptural media. Additionally, I was attracted to its ability to transmit light, which can really empower an art piece. It also offers inner space because of its transparent/translucent properties,” Segovia explains.

“I find it poetic to use textile techniques with glass,” she adds. “This is because glass is made out of sand. The same raw material provided ideal conditions for the survival of ancient textiles, allowing future generations to appreciate them and their message. Glass communicates light and, therefore, resilience. It communicates space; therefore, refuge or protection, and, yes fragility, all at once.”

A medley of Segovia’s techniques is currently on display at the Tucson Museum of Art exhibition CUMBI: Textiles, Society, and Memory in Andean South America, on view through February 25, 2024, in her installation Retablo de Imágenes y Memorias, which takes the shape of a shrine.

The retablo displays seven embroidered portraits stitched on water-soluble fabric and seven corresponding pairs of hand-made canvas shoes representing young people who have passed away in detention centers. The insoles feature complex embroidery portraits and life scenes based on photographs of the youth, their families, or their hometowns. “I feel that these children need my attention, patience, and time, and this is why I chose to create works that are labor intensive,” she says. “This [artmaking] process resonates with their long strenuous journey and the essential, undervalued work immigrants often do in this nation.”

When she exhibited Retablo de Imágenes y Memorias at the University of Arizona Museum of Art in 2022 as part of her MFA program, the double-sided shrine included twelve bright orange lockers, which Segovia replicated after visiting the Pima County Office of Medical Examiner storage facility in Tucson. The wall pieces contained items cast in glass—a hummingbird found in a deceased man’s shirt pocket, a toothbrush, a makeup compact, and a perfume bottle—that represented the belongings of immigrants found dead in the Sonoran desert. A nearby floor arrangement of glass-casted children’s shoes signified “multiple generations of immigrants’ children who are the keepers of their ancestors’ memories of courage, sacrifice, loss, hope, and the transcendent dream to live harmonious, fruitful, dignified lives,” writes Segovia.

Segovia says that she employs media and colors to catch people’s attention. As an example, she dissects Pasadores (2020), an oil-on-canvas family portrait that was part of the Arizona Biennial 2023 at the Tucson Museum of Art.

“The painting has vibrant colors and people were like, ‘Woo! Fun!’ Then they look at the shoes and may ask why they aren’t wearing shoelaces,” says Segovia. “Asylum seekers’ shoelaces are removed while in U.S. detention, and when they are sent back to Mexico to wait out the decision on their asylum request, they become identifiable as easy prey for kidnapping and trafficking.”

The painting also includes someone without a chair. “[The viewer may ask] ‘Why is it like a musical chair? Oh, a musical chair!’ And then maybe they ask why is somebody getting left behind,” she says. “As a former child seeking asylum in this country, as an immigrant of native ancestry to the Americas, I see my reflection and my family’s reflection in most immigrants that reach the southern border. My family is portrayed to epitomize an asylum-seeking immigrant family forced to play musical chairs while wearing shoes with missing shoelaces.”

Currently, Segovia is one of more than twenty artists—including Alice Leora Briggs, the late sculptor Luis Jiménez, and Alejandro Macias—exhibiting in Portraits at Pima Community College’s Louis Carlos Bernal Gallery. The show runs from January 29 to March 8, 2024, with a reception scheduled to take place February 15, 5-7 pm. Her piece Retablo de Imágenes y Memorias has been added to the Corning Museum of Glass’s public archive and featured in the Corning, New York, museum’s flagship publication New Art Glass Review.

Despite tackling the often maddening and depressing subject of U.S. immigration, Segovia is an upbeat person who wants to insert more happiness into her works—all while remaining an advocate for the immigrant’s journey. Segovia plans to expand her textile and glass techniques to encompass three-dimensional objects in works that bring her joy—“joy as resistance,” Segovia says.

“I want to make paintings of marginalized people being happy because they are deserving of happiness,” she says. “It’s not just about hardships because we’ve been able to overcome that.”