The Rita Deanin Abbey Art Museum in Las Vegas traces Abbey’s prolific but underappreciated career that remained cemented in Southern Nevada.

LAS VEGAS—A captivating museum devoted to the late American artist Rita Deanin Abbey (1930-2021) celebrated its second anniversary last month. A nonprofit spearheaded by the Robert Belliveau and Rita Deanin Abbey Foundation, the single-artist museum chronicles the trajectory of the artist, who established roots in Southern Nevada in the 1960s after developing an affinity for the desert oasis. Her career remains little known within and outside of the region.

Abbey was born in Passaic, New Jersey, and began her classical art training in the mid-1940s at the French Institute in New York, where she studied sculpture and figure drawing under the German classical sculptor Naum Los. She attended Goddard College in Plainfield, Vermont, and the Art Students League in Woodstock, New York, before venturing to the Southwest in 1950, earning her MA and BFA from the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. In the summers of 1952 and 1954, she returned to the East Coast to study under the Abstract Expressionist artist Hans Hofmann at the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts in Provincetown, Massachusetts.

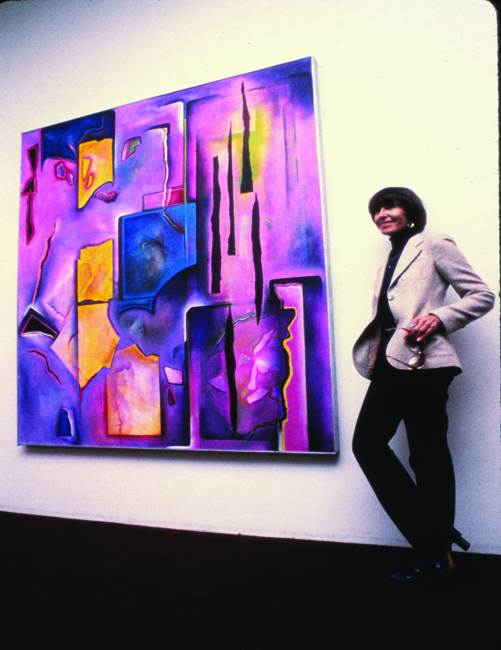

Her eclectic range of influences and interests are visible throughout the Rita Deanin Abbey Art Museum. Her various series diverge dramatically in style and media, and at first glance one of the most striking aspects of the exhibition seems to be that the works were all made by the same artist. From copper reliefs to bronze and wood sculptures, paintings, stained glass, all-black mixed-media works, and colorful plexiglass sculptures, one of the few recurring commonalities in the works is Abbey’s masterful and poetic encapsulation of desert phenomena and the sensuous and atmospheric quality of her approach.

Many of Abbey’s works contain autobiographical references. For example, various paintings, drawings, and sculptures dating from the 1950s onward are inspired and titled after sites in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, where she traveled with her first husband, the environmental author and activist Edward Abbey. One highlight is the Arches National Monument series (1956-59)—works depicting the topography of the national park, a central setting in her late husband’s writings. Others reflect Abbey’s interests in the performing arts and tai chi, like the bronze Bangarra (2003)—an anthropomorphic sculpture based on a photograph of her son Aaron, who was a dancer for several years and is now a board member of the museum.

Abbey worked prolifically throughout her life, having more than sixty solo exhibitions and participating in more than 160 group shows. The last major exhibition of her work came in 1988, when the Palm Springs Art Museum held the Rita Deanin Abbey 35 Year Retrospective in collaboration with the Marjorie Barrick Museum at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. She received two major commissions in the years that followed, both in Las Vegas, first in 1993 for Spirit Tower at the Summerlin Library and Performing Arts Center, a twenty-foot steel sculpture, and in 2000 for the monumental Isaiah Stained-Glass Windows for the main sanctuary of Temple Beth Sholom. Other pieces she completed can be found throughout the Vegas valley.

Despite these significant milestones, Abbey rarely exhibited her work outside of the Southwest, and never received commercial representation. She settled in Las Vegas in 1965, working as a professor in the art department at UNLV, and spending the remainder of her time in the studio. Although she never reached the echelons of her peers, she was featured alongside Michael Heizer, Walter McNamara, and other major artists in Mapping the Empty: Eight Artists and Nevada by William Fox, a groundbreaking 1999 record of artists working in the Great Basin.

“She did make efforts to become better known, but not sustained, deep efforts,” says Robert R. Belliveau, a retired pathologist whom Abbey married in 1985. “She always regretted the time that it took away from the studio. Especially in her later years, she just wasn’t that interested in selling works or promoting herself.”

Belliveau was instrumental in the founding of the institution and ensuring the preservation of Abbey’s work, beginning plans for the museum about seven years before its official launch in August 2022. The 10,500-square-foot building was constructed around her former studio, which is open to the public on docent tours. It includes an outdoor sculpture garden and works organized in thematic order, featuring about 175 pieces that will periodically rotate. The foundation has more than 2,000 works in storage.

“Rita had a vision that she would build a museum here, but for a long time she was fine with having just one or two galleries and knew that creating a museum would be a massive undertaking that would distract her from the studio,” says Laura Sanders, director of the Rita Deanin Abbey Art Museum. “She never stopped working and helped with the curation, but it was Robert who pushed her and she then finally acquiesced. He’s her number one fan, and he made it all possible—her Medici, so to speak.”

Sanders was first contracted by Abbey as an archivist, creating a searchable database of her entire life’s work that aims to expand research and scholarship on Abbey and her overlooked contributions to art in the Southwest. “She had a cult following but she knew that building a museum and archive would be an arduous task, so this is quite an achievement,” Sanders adds. “She really understood the desert in a way most artists don’t, but, beyond being a great artist, she was one of the most engaging and present people you could ever meet. When you were with her, you were really with her.”

The Rita Deanin Abbey Art Museum is also a landmark achievement for Las Vegas, where efforts to boost cultural offerings are just beginning to take shape and where once-obscure parts of art history are beginning to be rediscovered and valued. Honoring the forces of the surrounding natural world, Abbey’s work is executed with a high level of expertise and consideration of materials, but above all, it is imbued with a mysticism that is unique to the desert. As Abbey herself once wrote: “I strive to discover these forces through deeply felt, distinctive images rather than consistency of style. I submit to the rhythm and order of the power of change and motion in surroundings and in myself.”