As voting rights and the DACA immigration program took hits in Texas, Arizona artists Gloria Martinez-Granados and Joan Baron remain committed to John Lewis’s renowned call to make “good trouble.”

PHOENIX, AZ—As Texas legislators boarded buses bound for Washington, D.C. this summer, eager to champion the cause of voting rights, a pair of Arizona artists recalled the roots of their ongoing collaboration inspired by civil rights leader and United States Congressman John Lewis.

It’s been just over a year since Lewis’s death, and the march towards justice continues, aided in part by creative collaborators Gloria Martinez-Granados and Joan Baron, whose Good Trouble Bucket, first exhibited during early pandemic days, has proven profoundly prescient.

The installation is titled after Lewis’s iconic expression: “Get in good trouble, necessary trouble.”

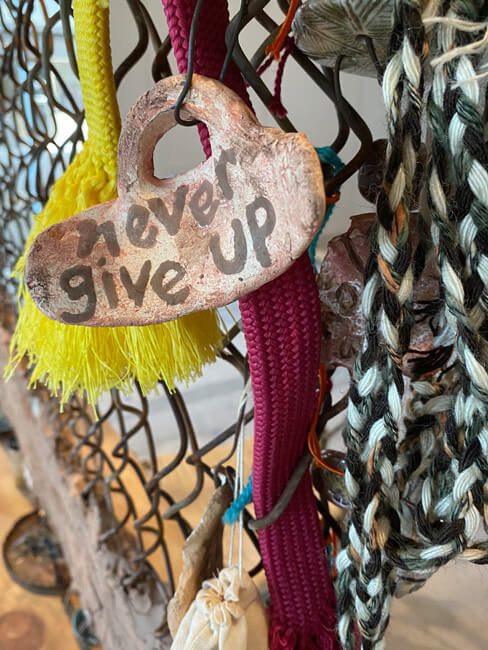

Anchored by chain-link fencing suspended above a long wooden table and soft clay forms of the artists’ own bodies, the mixed-media artwork speaks to voting rights, immigration, climate change, equitable access to food and water, and other urgent issues of the day.

“We created the work while Lewis was still alive, and we talked about making it a very political piece,” recalls Martinez-Granados, who immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico with her family when she was eight years old. “John Lewis was always a supporter of DACA and immigration, and he recognized that change only happens when we collectively organize.”

It’s a reference to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program launched by the Barack Obama administration in 2012, which confers legal status on eligible immigrants brought to the U.S. as children. In July 2021, a federal judge in Texas ruled that DACA is unlawful, effectively halting new enrollments in the DACA program.

That ruling is one of many reasons the installation remains so relevant, even as Baron and Martinez-Granados seek new opportunities to evolve and share their work.

For Good Trouble Bucket—initially shown in a pop-up gallery at Phoenix’s Park Central mall the same weekend that Austin, Texas launched a domino effect of COVID-19 shutdowns by canceling the 2020 South by Southwest festival—the artists incorporated an upside-down bucket amid objects including crystals and Native seeds. Atop the bucket, Martinez-Granados placed a fat pile of her own immigration papers. “It’s the stack my lawyer gave back to me after the first time I applied,” she recalls.

Knowing she has to undergo biometrics like fingerprinting and a retinal scan as part of the DACA renewal process, Martinez-Granados is particularly mindful of the ways Good Trouble Bucket amplifies body as landscape.

The piece includes performative elements, such as sharing foods from their distinct cultural traditions while seated on opposite sides of the fence that signals both physical and metaphorical borders, slowly walking a spiral with a bucket of water referencing the liquid’s healing powers, and shaping the clay that becomes a single body existing on both sides of the fence, looking up towards a shared sky.

Both artists culled from their personal histories, and those of their ancestors, while creating Good Trouble Bucket. For Baron, that includes her Jewish heritage and connections to the Holocaust. “We’re dealing with the same negative things we haven’t been able to get past,” Martinez-Granados says of living in the current climate of hatred and fear.

They’re continuing to collaborate, expanding on other shared interests such as food equity and climate change. One year into the pandemic experience, they created Mother Tree at the Four Corners, an outdoor installation at a small Phoenix farm where they wove fiber throughout a tree’s branches and imbued the landscape with sounds from a crystal healing bowl. They’re incorporating similar themes into a mural for a local elementary school.

Moving forward, it’s likely they’ll create fresh takes on Good Trouble Bucket. “We have ideas about how we can expand the body as landscape now that the physical forms we shaped with clay have been freed from the chain-link fence,” Baron says. The clay has dried, which brings a whole new layer of meaning. “We really like the symbolism of it crumbling.”

They’re talking as well about bringing in additional collaborators and transforming the installation to focus on bridges rather than walls. However it evolves, Baron says they’ll continue to find inspiration in Lewis’s work. “John Lewis was always standing up for what was the right thing,” Baron says.

Now, these artists hope their collaboration will inspire others to do the same.

“Art is a very important tool to have now because it survives through so many changes that can feel scary,” Martinez-Granados says of art’s role amid today’s heated rhetoric and divisiveness. “When volcanoes erupt, that material brings new life.”