Adama Delphine Fawundu submerses herself into the Great Salt Lake, activates the UMFA’s African collection, and brings the region into a global dialogue around decolonization.

salt 17: Adama Delphine Fawundu

September 13, 2025–June 14, 2026

Utah Museum of Fine Arts, Salt Lake City

Few artists are willing to stand inside the shadow of empire without flinching. To navigate the afterlives of colonial history and confront its greed and corruption, the erasure of ancestral knowledge, and the dismissal of ways of seeing that extend beyond the physical eye is to enter deeply demanding terrain. Yet in her salt 17 exhibition, Adama Delphine Fawundu descends into history’s deepest wounds and emerges radiant as an intellectual and creative force sharpened by the encounter.

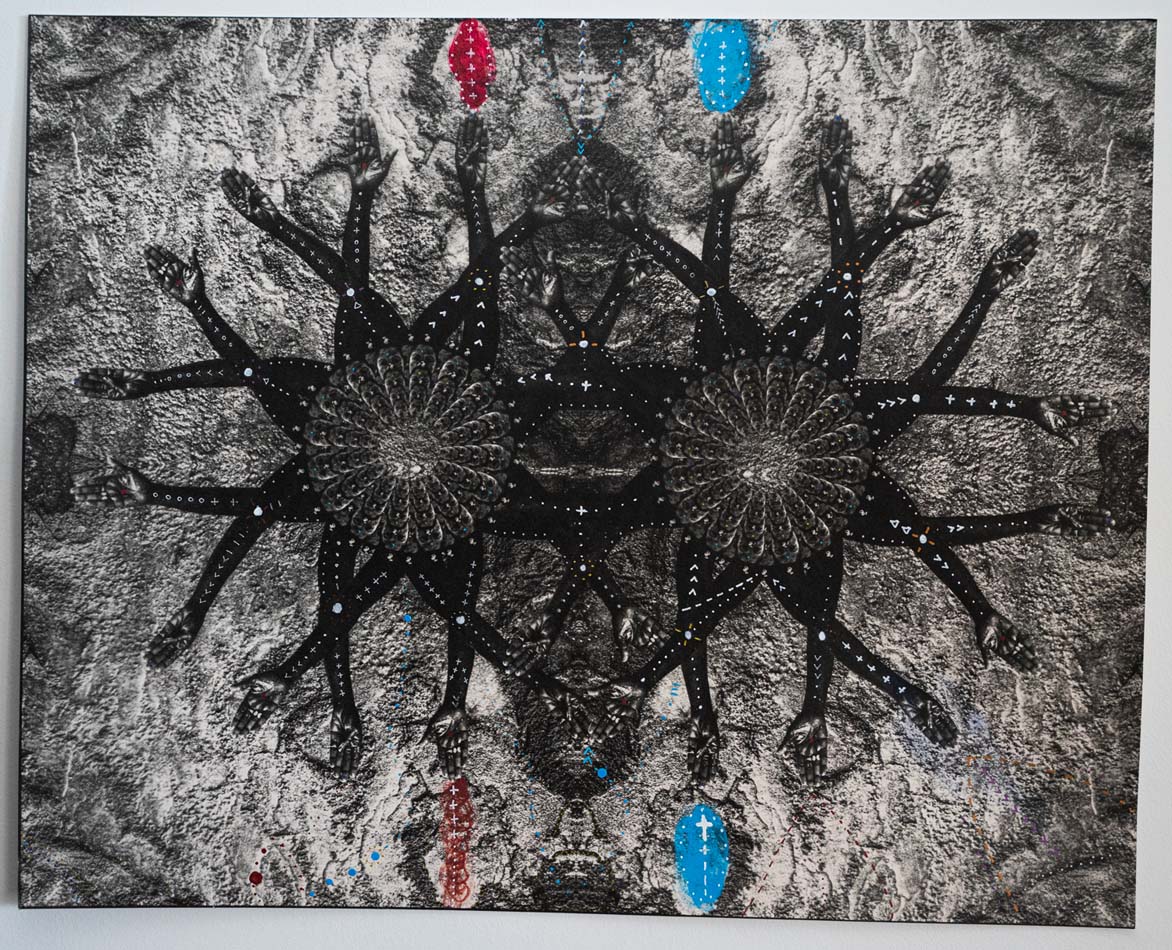

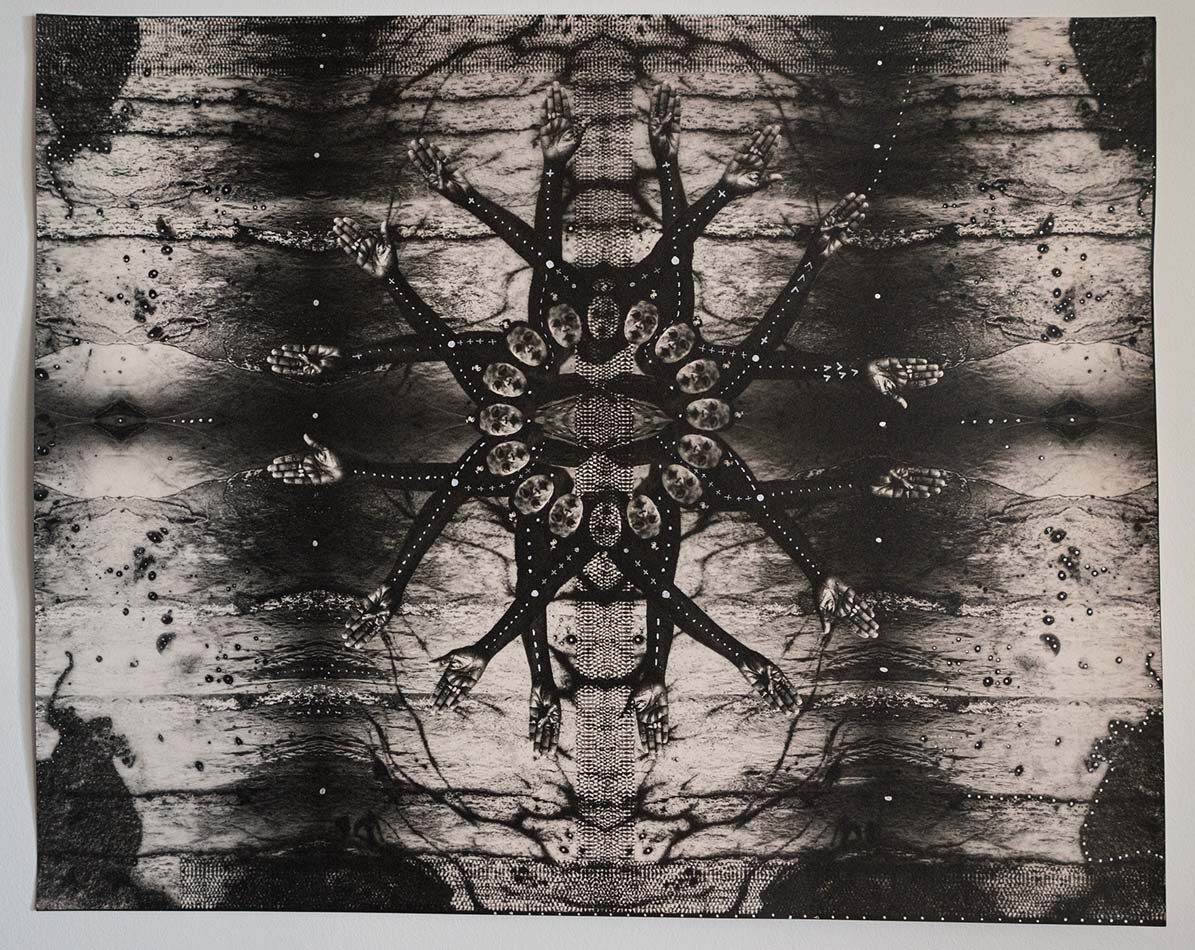

Born in New York and fully embodying her African roots and lineage (the artist is of Mende, Krim, Bamileke, and Bubi descent), Fawundu does not collapse under the weight of these histories. A rigorous transcontinental practitioner, she travels to historically fraught spaces, gathering materials for what she described in her 2025 UMFA artist talk as a “living archive.” The work carries heavy themes: the ravaging effects of colonization, the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade, the over-extraction of minerals and precious metals, and the ecological depletion built on the backs of enslaved peoples, yet it refuses to aestheticize suffering.

Water operates as a profound cosmological force throughout the exhibition. In the two-channel video installation Vibrations from the Deep (2025), filmed across Nigeria, Congo, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Brazil, and the United States, including footage from the Great Salt Lake, viewers become immersed in water, chanting, and embodied gesture. At the entrance, a wall text invokes the Yoruba deity Olokun, sovereign of the deep ocean and guardian of its mysteries. In Yoruba cosmology, Olokun governs the vast, unseen depths where abundance, memory, and spiritual force reside. The invocation situates water not merely as element but as sentient presence, as ancestral archive, as inexhaustible source.

The Great Salt Lake and the Congo River become unlikely mirrors, each bearing the mark of extraction.

Within the video, hair, adornment, and dress appear as systems of mapping and transmission. Chalk marks skin and ground, linking cross-cultural ritual practices. The two screens gradually merge, as if tidal currents were dissolving boundaries between geographies and generations.

Fawundu’s ritualized immersion in the Great Salt Lake grounds the exhibition in the ecological realities of the American West. As the lake recedes and its exposed bed releases toxic dust into surrounding communities, water becomes both absence and warning. In Utah, lithium extraction and mineral economies echo the extractive logics that have shaped the Congo for generations. By entering the saline water in a gesture of ritual care, Fawundu links inland drought to global mineral demand, reminding viewers that the infrastructures of technology and industry are tethered to fragile bodies of water. Salt preserves, yet it also signals depletion. The Great Salt Lake and the Congo River become unlikely mirrors, each bearing the mark of extraction.

Part of the decolonization process—which includes presenting objects as alive and connected to contemporary communities, and consulting those communities in how the objects are identified and displayed—that UMFA and Fawundu advance through salt 17 is a paradigm shift in museum display. Congolese objects from UMFA’s African collection are included in the exhibition not for historical illustration, but for the memory and intelligence they carry.

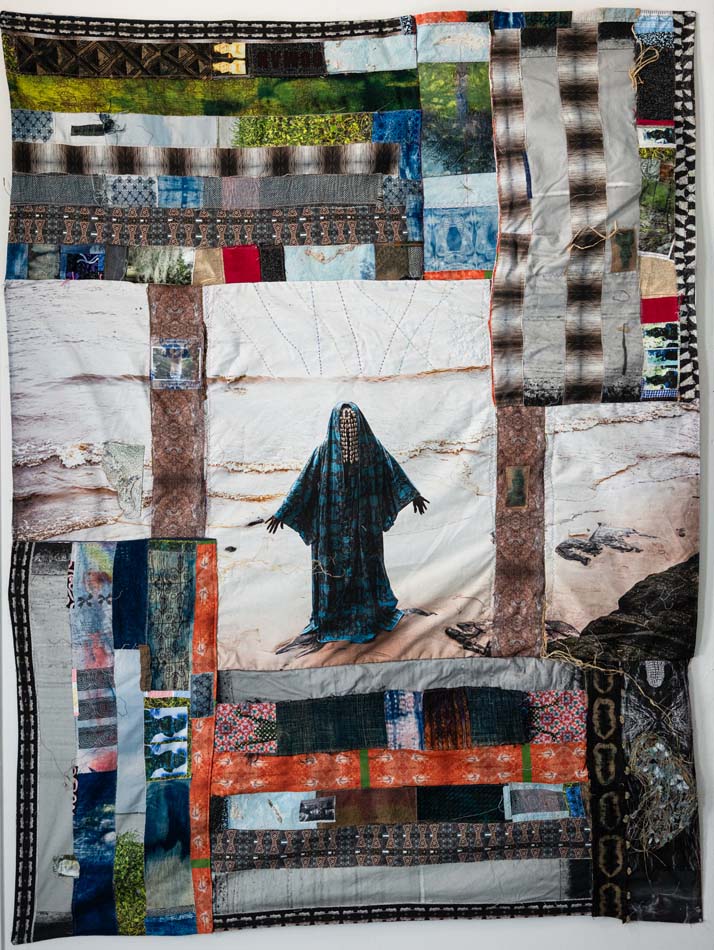

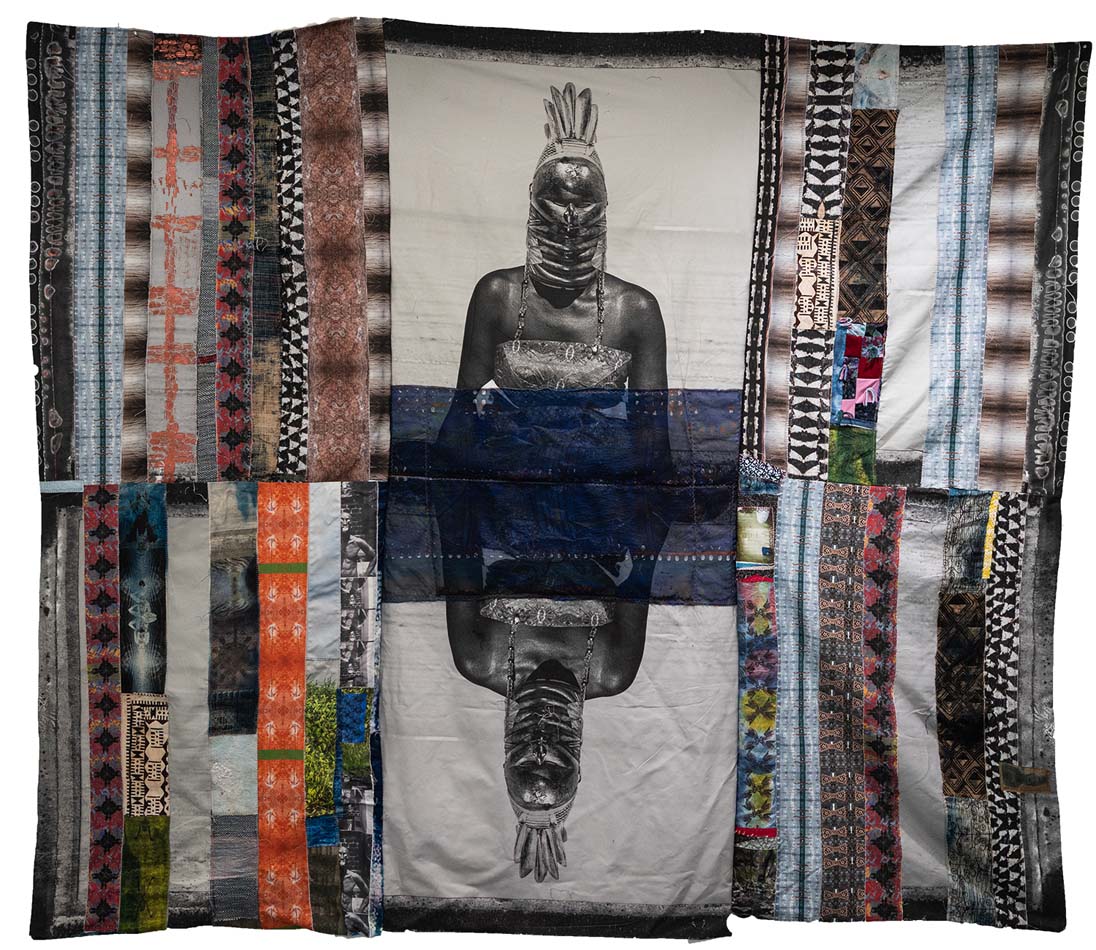

Fawundu selected six objects, including a mid-20th-century Kuba pendant ornament for a belt, nkody mupaap, woven in raffia with beads and cowrie shell, and a Kuba textile, likely a skirt, composed of raffia, bark cloth, and cotton. Their woven geometries and disciplined patterning reappear in Fawundu’s collaged textiles, where stitching and binding operate as a shared language across generations. Rather than isolating the Congolese objects within historical distance, curator Emily Lawhead, working closely with the artist, acknowledges their displacement and continued presence, creating conditions of activation instead of passive display. The historical and the contemporary do not compete; they pulse in reciprocal exchange.

Fawundu treats each element of her practice as collaborator, not just as medium. She says, “I’m interested in how materials move and feel, and how they are alive,” revealing her understanding that materials carry memory, human touch, and accumulated intention. Protection bundles containing shells, herbs, minerals, animal parts, and other things that remain unidentified, hold the presence of the minds and bodies that assembled, bound and activated them. Shells arrive with tidal histories and the protective life force of creatures that generated them. Herbs carry the labor and intention of those who cultivated them. Material is not inert matter but stored intelligence. When Fawundu states, “I live in the archive,” she positions her own body as both vessel and record, extending that intelligence through breath, gesture, and embodiment.

The historical and the contemporary do not compete; they pulse in reciprocal exchange.

Sîmba #1: feet grounded in the earth’s deep core, head crowned by a galaxy of stars—she sees: you are me, I am you, we are countless, yet one (2025) incorporates materials collected from different communities across the globe, including an antique quilt from Salt Lake City, handmade banana leaf with jute pulp paper, beads from Bahia, and cowrie shells gathered from Brazil, Nigeria, Congo, and Sierra Leone. The large-scale textile presents a mirrored upright and inverted figure stitched into a field of collaged fabrics that range from patterned strips to dyed and distressed cloth with visible seams. A deep indigo band cuts horizontally across the center, evoking water, horizon, and threshold. The composition reads as both altar and cosmogram. The mirrored bodies suggest cyclical time through descent and ascent, grounding and transcendence. Rooted in the earth and crowned toward the cosmos, the figures operate as an axis mundi, a vertical conduit linking terrestrial and celestial realms, the seen and the unseen.

The exhibition’s power lies not in scale, but in vibration. The artist’s concurrent inclusion in the São Paulo Bienal and the Congo Biennale situates salt 17 within a broader global discourse on diasporic continuity and restitution. Fawundu asserts that decolonization is not solely about repatriation or representation. It’s a recalibration of perception itself as she continues to expand her living archive with intellectual rigor and deep compassion.