various locations, Santa Fe

October 18 – October 22, 2017

I remember the moment when, as a teenager, I realized that the U.S. interstate system was built by humans. This doesn’t sound like any great epiphany, but to me it was jarring, because it meant that some of the largest structures I had ever seen—highway overpasses, ribbons of asphalt stretching for hundreds of miles—had been created based on the decisions of a small group of people. There was nothing infallible about this system, nothing preordained about its existence. I found this in some ways comforting (it meant that I too could contribute to the web of human creation) but in other ways unsettling (it also meant that anything could falter, that nothing is truly stable).

I am reminded of this realization now because many of the films I saw at this year’s Santa Fe Independent Film Festival reiterate this relationship between humans and larger systems, whether governmental, economic, cultural, or otherwise. Two documentaries in the festival addressed very material consequences of the systemic domination of capitalist structures. Atomic Homefront (dir. Rebecca Cammisa) focuses on a smoldering landfill adjacent to a Manhattan Project–era nuclear waste dump just outside St. Louis. Cancers are rampant and affect a large proportion of the suburban families living along Coldwater Creek and downwind of the landfill site. Even the Obama-era EPA avoided confronting the sickness of residents, and the film uses data gathered by a coalition of activists, the vast majority of them mothers, to counter governmental and corporate claims that there is no evidence of particulates from the landfill affecting residents. Republic Services, the corporation that controls the waste site (as well as the waste management of much of the U.S.), also seems to control the lawmakers, who refuse to prioritize the lives of the residents. The system has run far apace of quick-fix legislation, and as residents wait to be heard, people are dying; two people who participated in Atomic Homefront died of cancer during the span of the film’s production.

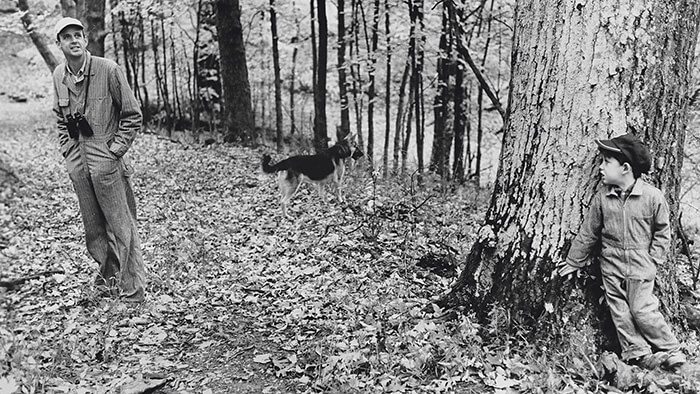

Look and See: A Portrait of Wendell Berry (dir. Laura Dunn and Jef Sewell) features residents of Kentucky who have farmed the land for generations. The film weaves together Berry’s iconic back-to-the-land writings with a history of how the U.S. government overtook small-scale, family-based farming practices in the 1970s and ’80s. In the wake of big agriculture, a cycle of harvest and debt hamstrings farmers who find themselves more and more removed from the growth of their crops every season and more bound to their bank loans and equipment and insurance bills. The filmmakers intercut scenes of farmers operating massive automated equipment with archival footage of the life of the small-scale farmer. But Look and See gets caught in an ideological eddy: an adherence to Berry’s doctrines seems to have blinded the filmmakers to some of the complexities of the present. For instance, immigrant labor, which is represented in the film mostly as a band-aid that could be discarded if only farming would revert to the good old days of family- and community-run plots, is a present-day reality in the U.S. that is the result of more than the simple scaling up of big agriculture.

On a more symbolic level, The Square (dir. Ruben Östlund), which opened the festival, is about trust and the decisions people make every day to help others—or not. Set in and around a contemporary art museum in Copenhagen, the film’s eponymous artwork, The Square, is a minimalist square of light on the ground. According to the artist’s statement, it represents a space wherein all people share equal privileges and responsibilities. Physically, the artwork sits at a remove from everyday life, idealized and rarefied in an institution of art, and the implication is, of course, that outside The Square, i.e., in literally the rest of the world, people do not enjoy such equity. Throughout the film, Christian (Claes Bang), the curator of the museum, is distracted and propelled by a series of increasingly uncontrollable events, which culminate in the unraveling of his professional life. In scene after scene, we see the social fabric being tested, being ripped and patched together, being stretched almost to breaking: in meetings with marketing consultants, in Christian’s confrontation with a small child he has wronged, in a journalist’s (Elisabeth Moss) bedroom after she and Christian have sex. In one of the film’s final scenes, Christian records a monologue into his phone in an attempt to explain a truly deplorable act. What begins as a heartfelt apology quickly devolves into an overgeneralized indictment of the “structural problems” of “society.” Christian’s failure to come to terms with his own individual culpability set the tone for the film festival for me and provided a through-line for the many films that pit individuals against systems so large and abstract that we forget that they, too, are only human.