Political organizer and artist Szu-Han Ho of Albuquerque builds coalitions and breaks down institutionalized barriers.

In an open and airy 1,000-square-foot storefront in Albuquerque, it’s easy to foresee this near-empty studio, recently occupied by Szu-Han Ho (she/they), coming alive with energy and ideas around movement and action. The artist and activist, whose works rely on fully embodied, immersive experiences, also shares the space with her art collective Fronteristxs.

Movement, organization, and collaboration, whether art-based or political, have always been integral to Ho’s creative practice.

“All those things that I’ve done still inform what I do now. But I think I’m so restless and that’s why art fits me because I’m kind of moving between things so much,” says Ho, who adds that her career trajectory “was definitely not mapped out.”

Ho, a graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, has lived in Albuquerque since 2011 where she is an associate professor of art and ecology at the University of New Mexico. A multi-disciplinary artist working in performance, sound, installation, video, image, and text, Ho never anticipated becoming an artist. After studying architecture, she ran a farm in Texas where she organized public events around installation and performance before returning to school for film.

An early art project, Taller de Intercambio, involved a cross-border artistic exchange between students in Culiacán, México and Albuquerque. “I was invited to do a workshop [in Culiacán] and I didn’t know anything about that space. I think I responded a lot to context and site and spaces and histories,” Ho says.

In the project, the two groups traded questions and answers about their respective environments, situations, and challenges. Each group then created a performative “score,” essentially instructions for an original art piece, for the other group to enact in front of an audience.

Taller de Intercambio gave way to Border to Baghdad, a collaboration between Ho and Rijin Sahakian of Sada Contemporary Art Center in Baghdad, Iraq. Over the course of a month, artists located on the United States-Mexico border interacted with artists in Baghdad through live video, images, and text. A record of these exchanges—as well as instructions for and enactment of a final performance “score”—were exhibited at the Rubin Center for the Visual Arts at the University of Texas at El Paso.

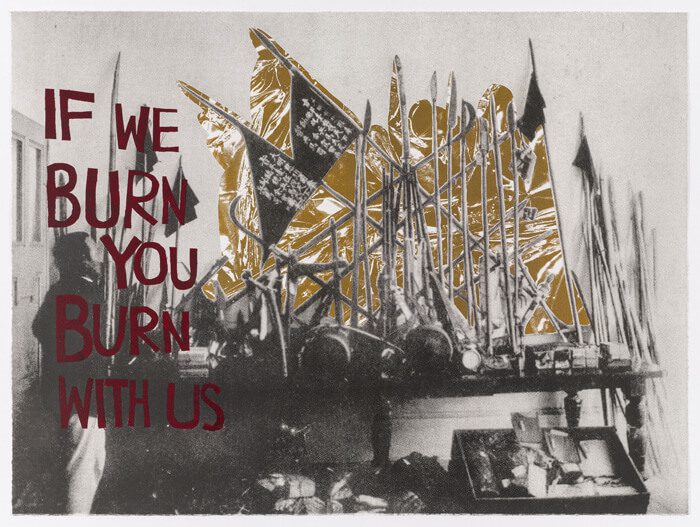

The two projects prepared Ho for her larger collaborative performance, Migrant Songs. The piece interweaves choral works, birdsong, narration, and bodies robed in mylar emergency blankets to explore the stories of individuals who have migrated from all over the world to live in Albuquerque.

Migration and the borderlands are prominent topics for Ho, who was born in Taiwan and raised in Lubbock, Texas. While she can draw a connection to her own background and upbringing, she says Albuquerque is a major influence.

“My students, my community, my friends [are all] impacted by being so close to the border,” she says. “[They have] families who have crossed or they themselves have crossed… the violence of the border is just ever-present here.”

It was her passion around borderland issues that led her, along with fellow artists and activists Bernadine Hernández, Martín Wannam, and hazel batrezchavez, to form Fronteristxs. The art collective grew out of a project she and Hernández completed in 2018. The two began organizing a network of artists across the borderlands, including Arizona, California, Texas, New Mexico, as well as Chicago, and have since mobilized through direct actions and large-scale art projects that include billboards, self-publishing, performances, and installations.

“The scope of what we do is really just about anything that we can do to point to the connections between the prison industrial complex, racial capitalism, immigration—all of those things are so connected,” says Ho.

Through the Prison Divest NM Coalition campaign, the collective successfully pressured the New Mexico Educational Retirement Board to divest from private prison companies. The victory came as a result of actions to petition legislators, public awareness through electronic billboards, and imagery projected onto detention facilities.

Much of the collective’s work involves “building coalitions with other groups,” says Ho, who adds that other partner organizations include People’s Budget, groups active with defunding police and pressuring the Legislature, and Albuquerque Anti-War Coalition. Fronteristxs is also collaborating with Working Classroom and Southwest Organizing Project to design and implement a curriculum for young people around art and abolition, for which they were awarded a $50,000 Art for Justice Fund grant.

Art and social justice are very much interlinked for Ho, who is most inspired by images from movements like the Black Panthers, Zapatistas, and radical Asian American groups. “I just think that everything we do has a social-historical context and I guess I like working with that,” she says.

In her own artwork, Ho is exploring her familial roots and gathering images of spaces from her parents’ hometown. She hopes to travel to Taiwan this summer to work on the project. For now, she admits she spends more time working with Fronteristxs, which she says is “as important to me as my solo practice.” According to Ho, the collective has really picked up momentum in the past two years, and it will continue to push forward.