Local artists and art-world power players are next-door neighbors in Winslow, Arizona. Everyone and the mayor is weighing in on the town’s creative direction.

This article is part of our The Hyperlocal series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 11.

In 1994, downtown Winslow, Arizona, presented a stark reality: boarded-up storefronts, a sign proclaiming “God Hates Winslow,” and local skepticism about its potential. Architect Allan Affeldt arrived to this scene, a place where a chamber of commerce member assured him tourism was an impossibility.

From this austere beginning, Affeldt and his wife, artist Tina Mion, initiated a transformation of Winslow, centered on the multimillion-dollar restoration of the abandoned La Posada Hotel, a Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter–designed masterpiece of Pueblo Revival architecture and former Harvey House. Their efforts, attracting a ripple of artists primarily from Southern California, have significantly reshaped the town’s trajectory, fueling a growing tourism economy.

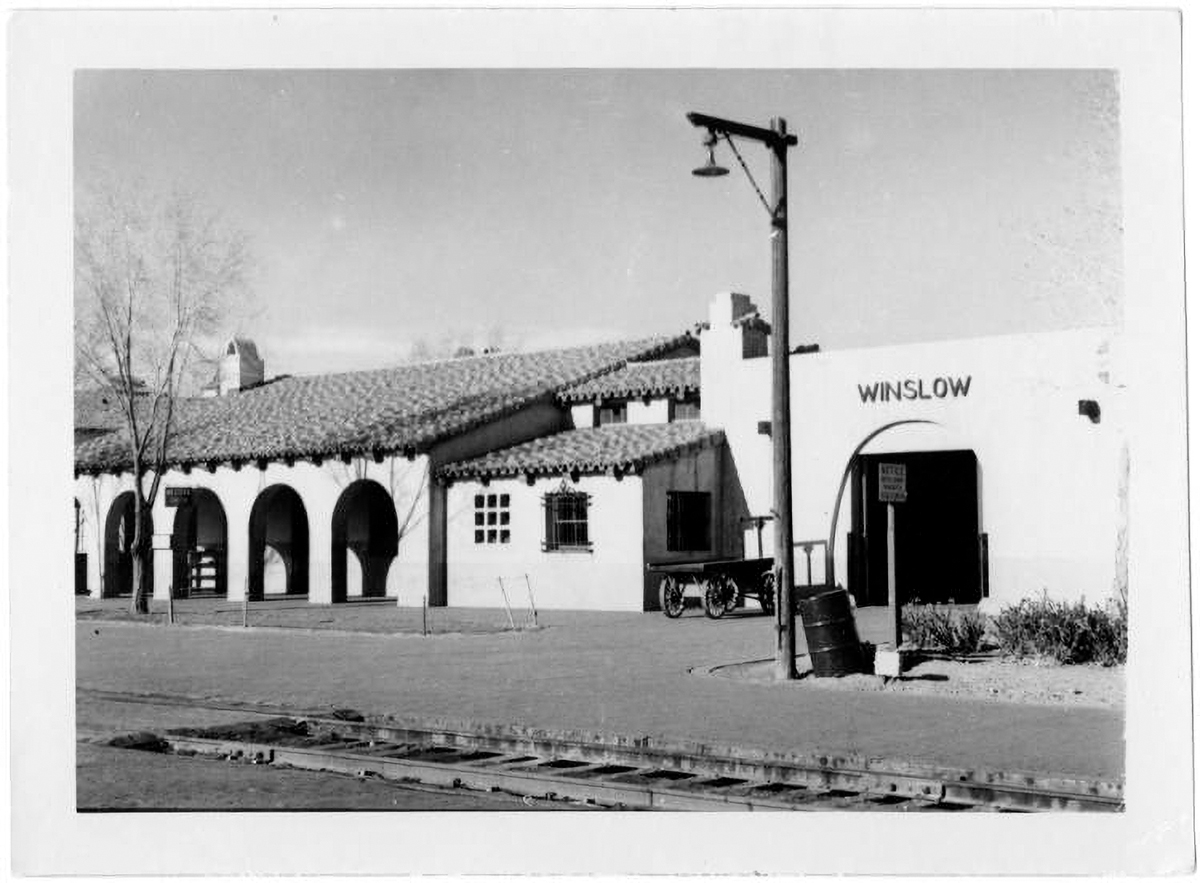

Affeldt’s vision extends beyond La Posada, encompassing a growing portfolio including the Affeldt Mion Museum, which opened in 2018 in a converted train depot, and plans for further art-centric development. He even served as Winslow’s mayor in the mid-2000s.

Winslow has undeniably been impacted by the influx of these out-of-state artists, which include Dan Lutzick, John Suttman, and Paul Ruschá (brother of Ed). However, not everyone in Winslow—a place rooted in Indigenous art and subject to cyclical economic shifts—remembers its past or envisions its future as Affeldt’s circle does.

Diverse voices within Winslow seek to participate in defining the town’s next phase, balancing preservation with the needs of all its residents. The question remains: how will Winslow navigate its renewed attention, and who will shape its evolving identity?

Lutzick, who owns the Snowdrift Art Space, a 22,000-square-foot building that serves as his and his wife’s private residence and public art space, is optimistic about the changes he has observed during his thirty-year tenure in town.

“I really do believe we’ve seen Winslow turn a corner, and they’re actually building steam. […] You know, if it’s a four block area, they’re buying properties five blocks out, and they’re working on it, because I think they can see that it’s coming their way,” says Lutzick.

The four-block area Lutzick is referring to extends out from 2nd and Kinsley, where Standin’ on the Corner Park, arguably Winslow’s biggest tourist attraction, sits. The park capitalizes on the Eagles’ song Take It Easy, which mentions Winslow—a relentless soundtrack that echoes from the loudspeakers in the intersection.

Growing up in the ’90s, [Winslow] was more like Santa Fe.

While the Winslow of three decades past is often remembered for economic stagnation, mayor Roberta “Birdie” Wilcox Cano (Diné/Ohkay Owingeh and Scottish/Irish), Arizona’s first Native American mayor, paints a different picture: a vibrant center of cultural life. Now, she’s harnessing that very energy, driving a revitalization that extends far beyond the familiar landmarks of Route 66 and Standin’ on the Corner Park.

“I remember the vibrancy, that’s what the downtown scene was—full of energy, people, shopping, commerce, conversations, and food,” Cano says. “It really was like something out of a movie.”

Cano says she understands what the artists of La Posada are cultivating, a different look and feel, but she associates Winslow with Hopi and Diné/Navajo art. “Growing up in the ’90s, it was more like Santa Fe. People would come and sell their artwork, crafts, pottery, and jewelry.”

Most of the creatives associated with La Posada live within a block of Standin’ on the Corner Park, a short walk from the hotel. Ruschá’s El Gran Garage warehouse, across the street from the Affeldt Mion Museum, which is connected to the hotel, anchors the other end of the four-block area.

“Because most of these artists are sort of in the central corridor, and because they weren’t born and raised in Winslow, they all kind of live in the bubble of their studios. So I don’t think their work is really being informed by the community they’re in,” says Lori Bentley Law, the creative director of Affeldt Properties and the Affeldt Mion Museum.

In 2018, Law and her husband relocated from Southern California to Winslow, where they purchased a historic building. Now known as the 66 Motor Palace, it houses their collection of vintage motorcycles. Passersby, as they amble away from Standin’ on the Corner, often mistake it for a storefront and stumble into their front door if it’s unlocked.

Don’t get me wrong, I like Marfa…. I don’t want [Winslow] to be Marfa.

Articles discussing La Posada and the Winslow Studio Artists, a moniker for its prominent creative clique, have compared Winslow to Marfa, Texas. One article states that Lutzick doesn’t like the comparison, which I ask him about.

Lutzick responds, “Don’t get me wrong, I like Marfa—I love going to Marfa, because you see parts of it working, and you see parts of it not working. You see people coming from a long distance and you see locals who aren’t necessarily thrilled with those out-of-towners coming in, you know? I take some comfort in the fact that everyone has to go through it, even if they’re Donald Judd.”

He emphasizes, however, that he does not want to apply the Marfa model—a foundation taking over most of the town’s historic buildings, as the Judd Foundation did in Marfa—to Winslow. “I don’t want it to be Marfa. At the same time, if we gain more momentum on an arts and culture level, I would be very happy about that. I don’t know if that is what the town, the general population of the town, would be most interested in. They want jobs, more restaurants, more stores.”

La Posada Hotel and the Affeldt Mion Museum have historically focused on the Winslow Studio Artists, plus other connected artists like James Turrell, who resides in Flagstaff. Turrell’s presence at the Hotel is marked by a trailer parked outside the museum, where he lived while mapping out Roden Crater. (Affeldt shares that Turrell is also designing a Skyspace for the museum.) Law, Lutzick, and Suttman all mentioned that they would welcome the idea of opening the museum to other artists, and that has been an ongoing conversation with Affeldt.

Affeldt says an early working title for the Affeldt Mion Museum was the Route 66 Art Museum. “The idea was that Route 66 has this kind of kitsch connotation in the popular imagination. […] But in fact, there were many significant artists who either grew up on, worked on, or were inspired by Route 66—but yes, the idea is to incorporate a bigger world. But our world right now is, you know, the people who have essentially created this space from what was just ruins.”

Affeldt plans to expand the museum into some neighboring buildings, drawing inspiration from the Menil Collection in Houston. He ultimately hopes to create a small-scale version of the Menil’s expansive art campus.

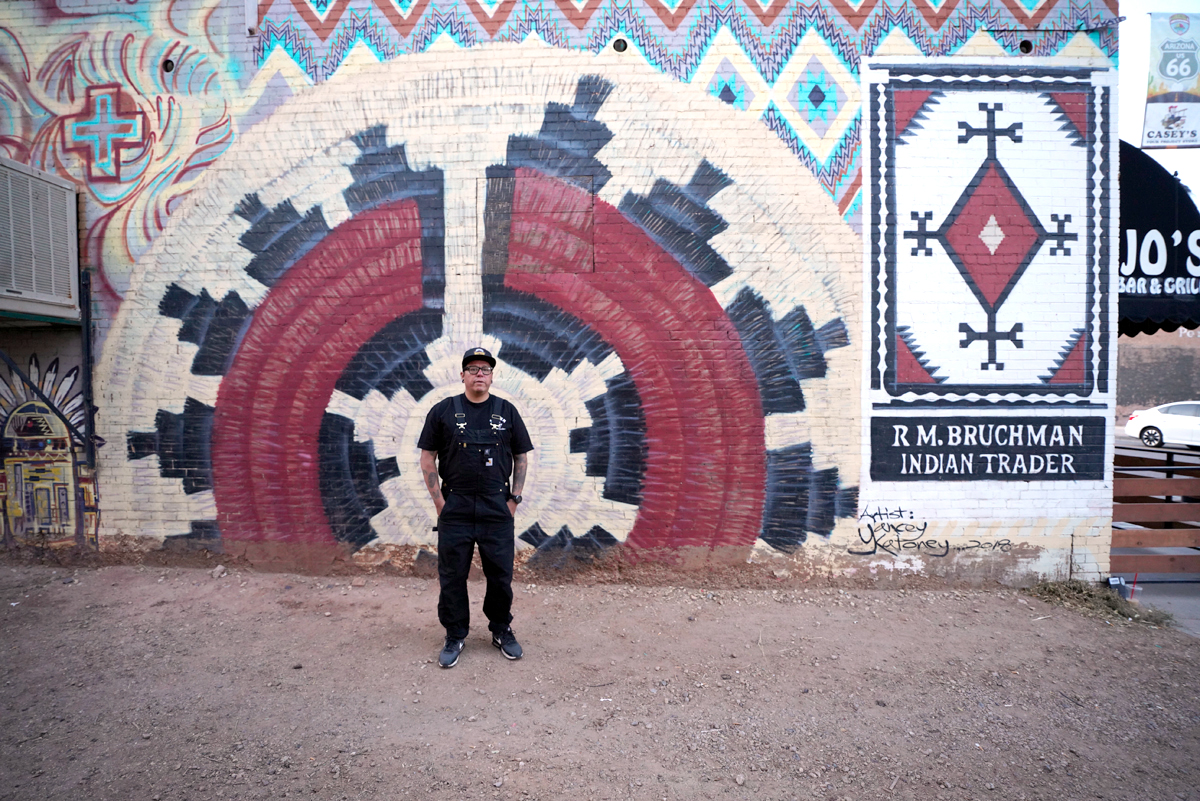

Born in Flagstaff and raised in Winslow, artist Marlowe Katoney (Diné/Navajo) highlights the Affeldt Mion Museum as a source of inspiration, one of few in town. He likes to go there to see the work being exhibited. However, he points out that the artwork there is “all California artists.” When I ask if he has shown there, he says he has not been invited to do so yet. Marlowe recently presented a solo exhibition of his weavings, which blend Diné/Navajo, street art, and pop culture aesthetics, at the University of Arizona Museum of Art in Tucson.

One of the Affeldt Mion Museum’s major permanent exhibitions is the Hubbell-Joe Rug, the largest known hand-spun and hand-carded Diné/Navajo rug. Katoney mentions this masterwork but is quick to contrast it with his own output: “For me, especially me, the work that I do is way out there, and when you see my work, it doesn’t communicate as Native American art.”

Katoney’s brother Yancey is a Diné/Navajo muralist and tattoo artist whose murals appear across Winslow’s downtown. Yancey recalls past discussions with Law regarding a potential mural commission for La Posada Hotel.

Deeply rooted in their Winslow upbringing, the Katoney brothers are committed to its cultural evolution, contingent on viable economic opportunities and affordable living. Their vision hinges on the town’s ability to cultivate a sustainable creative ecosystem. Yancey emphasizes his desire for more creative collaboration, but notes the limited number of artists pursuing his specific medium within the community. “People have been emailing me about residencies, and that means even more potential for collaboration. But you have to leave Winslow to collaborate with other artists, with other tribes.”

We like to balance things out in our community because we don’t need much.

Meanwhile, Winslow-based artists like Manuel Denet Chavarria (Hopi) and Marlinda Kooyaquaptewa (Hopi) are fostering another kind of hyperlocal art scene. Chavarria, a katsina doll carver, and Kooyaquaptewa, who co-manages Corn Maiden Traditional Traders, a new co-op for Native artists on 2nd street just two lots over from Snowdrift Art Space, emphasize the importance of supporting and promoting local artists.

A married couple, Chavarria and Kooyaquaptewa moved into the building about a year ago. They live in a one-bedroom apartment at the back of the building, where Chavarria keeps a humble work studio. Kooyaquaptewa runs the co-op with a business partner, Marley Arguello (Apache), and currently works with ten Native artists who sell their work in the storefront.

“Hopi didn’t always see themselves as artists, weren’t really artists,” says Kooyaquaptewa. “They call what we do art but everything is functional. The katsina dolls, the pottery, the baskets, the weavings, and everything that is part of who we were. When Route 66 brought tourists through Winslow, they became fascinated by Kachina dolls, the pottery baskets, you know, the attire and everything.”

Chavarria and Kooyaquaptewa’s approach reflects a deep connection to Hopi traditions and a commitment to community-based economic development. They practice a form of mutual aid, supporting fellow artists financially or providing art materials during slow seasons and reinvesting their earnings back into the community.

“We like to balance things out in our community because we don’t need much,” Kooyaquaptewa explains.

Chavarria adds, “It’s not just going to be a Native thing; I keep stressing that because we are all striving to succeed as artists. So, looking at it as an artist community overall, instead of breaking it down and categorizing things, does a lot better.”

One of the hardest things is trying to convince 10,000 people that they’re worth good things again.

Winslow mayor Cano also sees potential in artist cooperatives as a creative solution to the considerable expense of maintaining commercial space. Flagstaff’s limited industry and job opportunities, coupled with escalating costs and inflated real estate valuations, have turned Winslow into a de facto bedroom community for nearby Flagstaff.

For Winslow, years of economic hardship and neglect have led to a sense of stagnation and lowered expectations, Cano observes. “One of the hardest things is trying to convince 10,000 people that they’re worth good things again. That they’re worth these opportunities, and that it could really happen,” she says.

Winslow’s movement toward growth is a delicate dance between honoring the past and embracing the future. The challenges are real. Limited exhibition spaces, high rental costs, and a lack of previous investment in infrastructure are hurdles that Winslow must overcome. Whether Winslow will stick to its Route 66 mythologies, further strengthen its Indigenous arts roots, or follow the Marfa or Menil models, remains to be seen.