The Utah Museum of Fine Arts acquired thirty-five works by Chiura Obata, a visionary whose imprisonment at the Topaz camp is among the nation’s most shameful episodes of racial injustice.

SALT LAKE CITY, UT—By the time he was imprisoned at the Topaz internment camp in September 1942, fifty-six-year-old Chiura Obata had amassed a reputation as an accomplished artist, illustrator, and renowned art professor at the University of California, Berkeley. Obata was Issei, a first-generation Japanese immigrant to the United States, after arriving in California at age seventeen. Like his fellow Japanese Americans, Obata fell victim to wartime prejudices that reached a fever pitch after the December 7, 1941, bombing at Pearl Harbor.

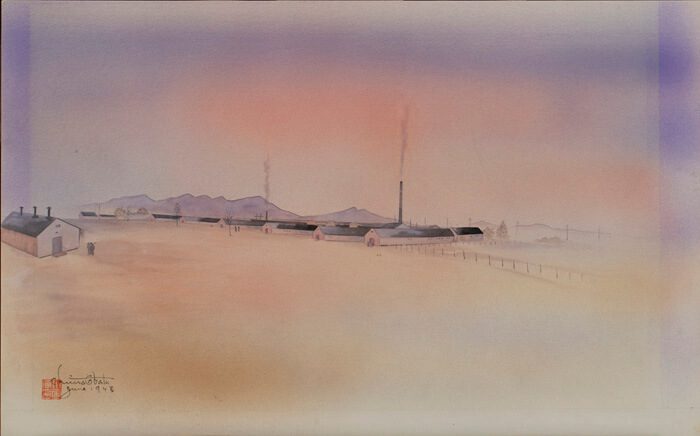

Now, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts in Salt Lake City has acquired thirty-five works by the artist, widely considered among the twentieth century’s most important Japanese American artists. A gift from the Obata estate, the works feature drawings and paintings created by Obata when he was jailed at the Topaz internment camp near Delta, Utah during a supreme act of racial injustice.

Additionally, the acquisition of the pieces—which also includes “watercolors, drawings, and prints of flowers, animals, and iconic California landscapes,” according to the museum’s press release—not only illustrates Obata’s visionary talents but also creates a powerful context that can help the viewer contextualize and realize a fuller and more inclusive view of American history.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans became the victims of widespread vitriol and aggression, culminating in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, signed on February 19, 1942, which mandated distinct military zones and the creation of ten internment camps for the over 120,000 Japanese American individuals residing on the West Coast. This included the Topaz War Relocation Center, an American concentration camp that incarcerated individuals of Japanese ancestry during World War II. The internment center operated from September 1942 to October 1945.

Time would demonstrate that roughly two-thirds of this population were American citizens and none among them were ever found guilty of espionage against the United States government. Nonetheless, the United States Supreme Court, in the landmark case Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214, 1944, deemed the flagrantly unconstitutional and immoral act a “military necessity.” It wasn’t until 1988 that President Ronald Reagan formally apologized and signed the Civil Liberties Act, which would provide $20,000 compensation to survivors.

During his year at Topaz, Obata founded the Topaz Art School, a prolific endeavor that retained sixteen instructors and approximately 600 students at its peak. He worked alongside fellow artists Miné Okubo and Matsusaburo Hibi. Okubo, a prolific artist and writer, crafted Citizen 13660, an illustrated novel highlighting the immense hardships suffered by Japanese Americans during the war.

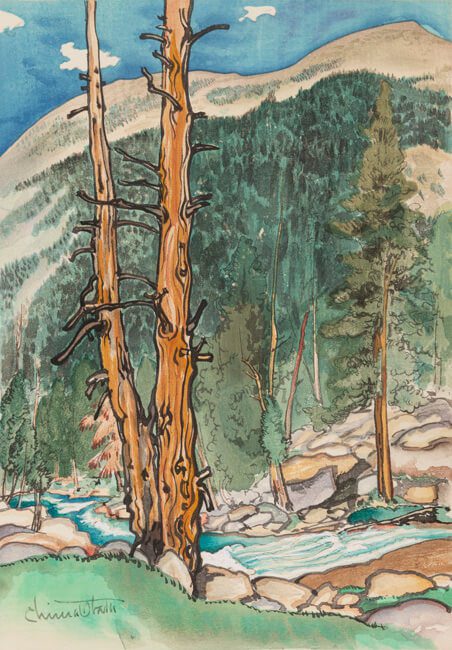

Though his impact there was momentous, Obata’s tenure at Topaz was a blip on the radar of an otherwise illustrious career. During World War I, he was an illustrator for the magazine Japan, and in 1921 he spent a prolific summer sketching and painting some of his most celebrated works of Yosemite National Park. After the Second World War, Obata’s work would grapple with the devastation wrought on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In 2018, the UMFA hosted the traveling exhibition Chiura Obata: An American Modern, a selection of 150 works from Obata’s prolific career. In 2015, the Topaz Museum—home to comprehensive historical exhibitions as well as art and artifacts created by internment camp detainees—opened in Delta near the site of the former camp with the inaugural art exhibition When Words Weren’t Enough: Works on Paper from Topaz, 1943-1945. The UMFA has been working with the Obata estate since 2017 to bring these works to the museum, which also includes the purchase of three additional pieces. (Obata passed away in 1975 at the age of eighty-nine.)

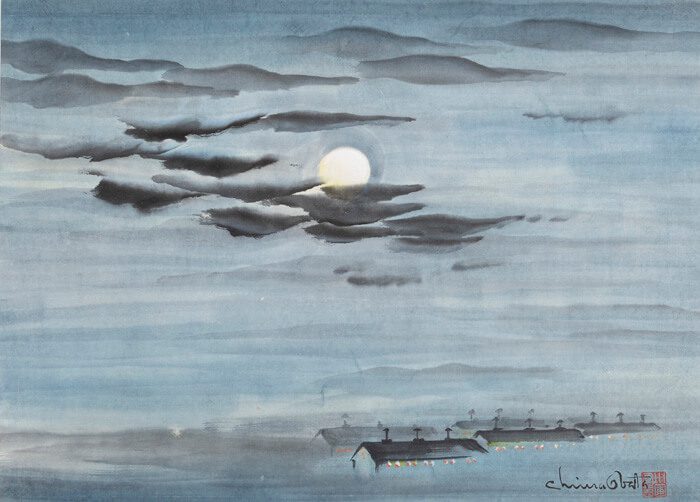

“Chiura Obata is one of the most important twentieth-century Japanese American artists. His search for what he called ‘Great Nature’ would produce new and unique images of the American West,” says Luke Kelly, UMFA’s associate curator of collections. “Even in the dark period of Obata’s incarceration at Topaz, he could still find beauty and peace in the landscape. The museum is very honored to have his art and display it in the American galleries,” which will be available to view starting fall 2022.

Obata’s work showcases his exemplary artistic talent—a command of watercolor and traditional Japanese sumi-e tradition, as well as a never-ending artistic curiosity captured by his enchanting scenes of the natural world. His Topaz works stand as a testament to an artist bent on discovering beauty amid the pain of war and racial injustice.

Obata’s granddaughter Kimi Hill recognizes the significance of housing the pieces in the state where her grandfather was once imprisoned.

“Because many of these artworks were created in Utah, we hope people will be inspired to learn the history of wartime incarceration and go visit the actual campsite in Delta as well as the Topaz Museum,” she says in the museum’s press release.

While having such works in Utah may remind us of the state’s participation in one of America’s most shameful episodes of racial injustice, it’s equally important to remind us that such episodes should not be siloed from our view of American history, but instead incorporated within it. Put differently, Obata is not merely a significant Japanese American artist, but an American one—seeing his work in the historical context in which it was created makes for a richer understanding of our shared American history.

Disclosure: Scotti Hill curated the Topaz Museum’s 2015 exhibition When Words Weren’t Enough: Works on Paper from Topaz, 1943-1945.