Thousands gathered for Zozobra 2023 in Santa Fe to stuff their sorrows into a fifty-foot puppet and watch the effigy burn to the ground.

SANTA FE—When I arrived in Santa Fe on September 1, 2023, for the ninety-ninth celebration of the Burning of Zozobra, the annual incineration of a fifty-foot paper and cloth effigy constructed in the style of a ghost-clown, the first person I talked to was a man holding a sign that read, “Turn to Jesus or Burn.”

He and a fellow evangelist were proselytizing at the gates of Fort Marcy Park, where 60,000 people were expected to gather for the ceremonial combustion that kicks off the Fiestas de Santa Fe every year on the Friday before Labor Day.

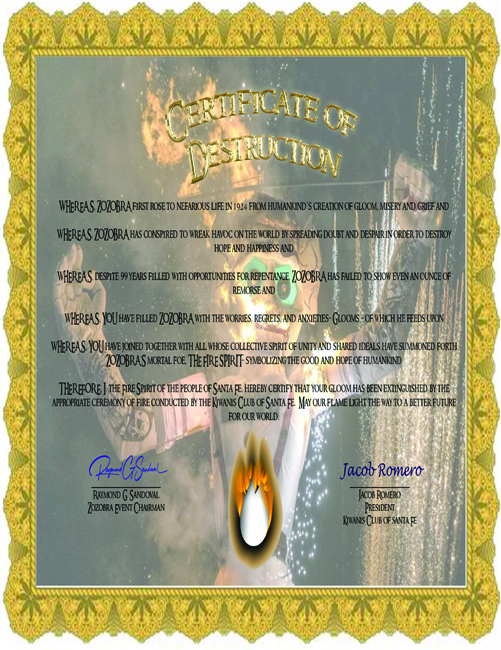

It was my understanding that we were here to burn Zozobra in order to expunge any bad vibes before winter settled in. It had been described to me by the event chair, Raymond Sandoval, as a “beautiful act of catharsis.”

The evangelists continued. They warned about the Lake of Fire that awaited all sinners. Evocative rhetoric, but how did that pertain to this city-sponsored, Kiwanis Club-benefiting event? I wanted to know: why would I be the one to burn?

I saddled up to one of them and asked what all this was about. “Only Jesus Christ can save you from your…” He turned to his partner. “What do they call it?”

“Gloom.”

“Yeah, from your gloom.”

“Gloom” is Zozobra vernacular for any kind of bad juju. (Zozobra is also called Old Man Gloom, and though “zozobra” means “anxiety” in Spanish, I suppose “gloom” was preferred for its elegance. Besides, “Old Man Anxiety” could mean something quite different.)

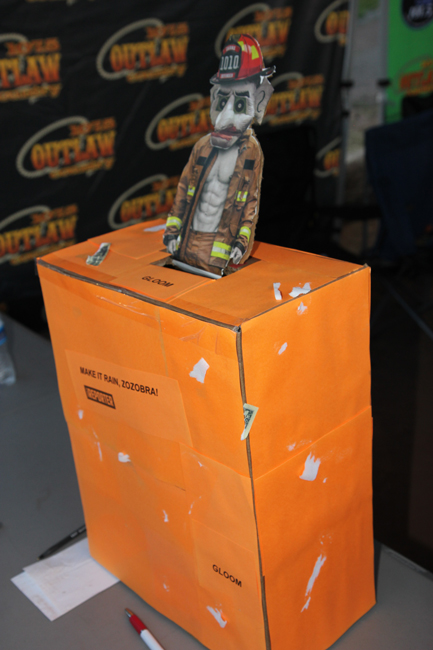

“Gloom” can refer to general malaise, as in the collective gloom of New Mexico. It can also refer to a specific piece of paper on which you list the problems you wish to expel from your life, as in “a gloom,” which can be purchased from burnmygloom.com prior to the event.

For as little as $1, Burn My Gloom volunteers will print your problems and stuff them into Zozobra. For serious or appendage-specific glooms, those who subscribe to some kind of pins-in-a-voodoo-doll logic can choose where in Zozobra’s body their gloom will reside ($5-$15 extra, depending on location).

I waited for the evangelists to expound on the crimes of idolatry or at least ask for my email address. But they didn’t, and though I wasn’t exactly moved by the interaction, I was a little spooked. The fact that they were even here proved that this effigy was serious business.

But if my intuition rang any internal warning bells, they were eclipsed by my neurotic compulsion to find out for myself. And so I thanked them, turned around, and walked straight toward the gates, through the press pass express line, and toward the altar of the false idol.

As it turned out, the false idol was no joke, standing five stories tall with glowing eyes and a dead man’s complexion. I’d been cavalier with the evangelists out front. But once I caught a glimpse of Old Man Gloom inside the park, I no longer felt quite so strong in my convictions.

What immediately unnerved me was the normalcy of it all. I could have been at a free concert put on by the Parks and Recreation Department judging by the family picnics and the fleet of food trucks selling fry bread and popcorn. This scene of wholesome summer fun against the backdrop of a nearly one-ton goblin billowing gently in the twilight breeze gave me pause.

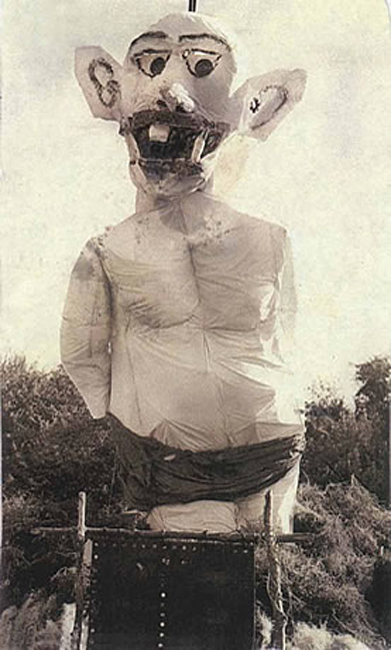

Zozobra’s appearance varies slightly from year to year. But the core characteristics have stayed consistent since its inception in 1924. These include ghost-white skin, a thick-lipped pout, and ears so large they look more like the frills of a lizard’s neck. He dons a black-and-white tuxedo jacket on top and a ghost tail (not a skirt! I was corrected more than once) on bottom. Throughout the years, his hands have expressed a variety of gestures including finger guns, fingers crossed, closed fists, and the sign of the horns (rock ‘n’ roll).

He’s also a marionette—in 2007 he held the Guinness World Record for largest puppet—and his arms, head, and jaws are controlled with a pulley system. His eyes are animatronic.

For the past few years, the group of volunteers who coordinate Zozobra have been building anticipation for next year’s 100th anniversary by theming each burn leading up to the centennial by decade. Two years ago, it was ‘80s-themed, and last year was ‘90s. Apparently impatient to get through the 2000s, this year paid homage to Y2K cultural touchstones from the early aughts and the twenty-teens.

As such, Zozobra was accessorized with a wand and black cloak like the villain that defined the Harry Potter generation, Lord Voldemort.

Zozobra’s construction usually costs about $10,000 and began this year in May. But collecting the paper that constitutes his insides takes all year, said Jacob Romero, Zozobra’s lead fabricator for the past twenty-two years.

“We source paper from a lot of state agencies,” he said. “Case records from the police department, bank documents. We get stuff from the public, too. Bankruptcy paperwork, tax returns, court filings.”

This past year, Romero was a juror on a first-degree murder case. “Some of the documents I was privy to. I got permission to keep them and put them in Zozobra to dispel that gloom,” he said.

I asked Romero if it’s hard to burn something he works so long to create each year. “The art piece hasn’t served its purpose until it’s gone. The final stroke to that painting is setting it on fire,” he said. “I actually embed my worries into the frame of Zozobra. That’s not something that you want to stick around.”

Stuffing the effigy is a community event, he explained, and the public is invited to the workshop to beef up Old Man Gloom with flammable woes in the weeks leading up to the ceremony.

Dressing Zozobra requires the assistance of nearly forty people, he said. They usually have five tailors working at once and need about thirty people just to hold the fifty-foot strips of fabric while they sew.

I asked Romero what Zozobra was supposed to be. “He’s what makes the dogs howl,” he said. “He’s a nightmare.” Ok, but why does he look like a ham-fisted clown with a botched Botox job? “He’s Will Shuster’s vision,” he said, referring to Zozobra’s original creator. “We follow Shuster’s blueprints almost to a T.”

In the 1920s, Shuster traveled to Mexico during Lent and witnessed the burning of an effigy of Judas. Inspired, he recreated a version of the tradition back in Santa Fe. (Someone should tell the Christian protestors!) Today, the event claims no religious affiliation.

According to a documentary by KOAT-TV in Albuquerque, Shuster built some Zozobra lore by publishing a series of fake news stories in the Santa Fe New Mexican that claimed a giant was caught in the mountains, brought back to town, and burned.

Over the years, Sandoval explained, the legend has morphed and solidified into something that more or less goes like this: all year, Zozobra hides in the mountains and feeds on negative energy. Come September, the city devises a trick to destroy him. He’s invited to a party to celebrate the Fiestas de Santa Fe, and he dresses to impress, hence the tuxedo. Upon arriving in Santa Fe, he plunges the city into darkness and turns the children into a gloom-bearing army. The townspeople take up their torches to fight for their children, invoking the Fire Spirit, which brings Zozobra’s demise and releases the children from their trance.

Sandoval had to put me on hold more than once during our phone call when he was telling this story because the city had, in fact, been plunged into darkness—a power outage—and he was on the clock for his day job, communications director for the electricity provider, Public Service Company of New Mexico, or PNM.

“Anyway,” he said when he came back on the line. He had lost his place in the story. “Santa Fe is a crazy city. Where else can you burn a fifty-foot marionette one mile from downtown?”

Before posting up for the spectacle, I visited the gloom tent where a woman was collecting last-minute gripes. I took out my notebook to write down my woes, but I was feeling superstitious. What did I want to get rid of? But more importantly, what would it cost me? I thought about other times I had gotten exactly what I asked for and regretted it. Fate’s cruel mockery: You asked for it!

But in the end, I figured, fuck it. I didn’t drive 400 miles from Moab to Santa Fe just to pussyfoot. With a complete lack of ceremony, I slipped my gloom into the cardboard gloom box. I asked the gloom box overseer if anyone had put anything crazy in there.

She opened the box and revealed a red-and-white checkered keffiyeh, a headscarf worn by men in Middle Eastern countries. “Something about the patriarchy,” she said. This seemed very possibly racist, but she had already shifted her attention to the gloom holders behind me before I could ask for some context. I walked to the other end of the tent where a wedding dress hung from the frame. “We always get at least one,” said a different gloom coordinator. This year there were two.

As I snaked my way back to my post, a woman lost control of her LED hula hoop, and it hit me square in the stomach. I took note of the vibe shift among the crowd. The gates had opened at 4 pm, and there wasn’t much else to do besides drink and look at the bogeyman.

The energy was building, entropic. Still, it wasn’t quite the variety of hooting and hollering I had expected, something more curated or perhaps pagan. But I suppose with a crowd this large, it had to pander to the lowest common denominator. This was not unlike a hometown carnival. It was all funnel cake and glowsticks and kids tooting one-note plastic horns.

The ceremony preceding the burn was deliriously long, long enough for night to fall and for the moon to trace a slow arc from stage left to stage right, so long it made an exasperated woman behind me yell, “Just burn him already!”

Alan Webber, the mayor of Santa Fe, was invited to say a few words, but all I noted was the hefty “boo” he received from the crowd. The breeze was picking up. Someone backstage had left their mic on, and the wind groaned womp womp over the loudspeaker until the P.A. screeched with feedback. Spooky, but probably not what they intended.

The sponsors were thanked in excess. Among them, I noted a crematorium. At one point, a frantic search for “Bert West” began. A large man with a headset microphone and a clipboard was pleading, “Bert West, come to the stage. Bert West, where are you?” As it turned out, Bert West was not a lost child but the president of Kiwanis International, a lesser-known of the service clubs à la Rotary, Lions, etc., which hosts the effigy burn every year on behalf of the children of Santa Fe and the world.

“Thanks to you, we put smiles on children’s faces,” West said when he finally appeared. “Let’s keep putting smiles on kid’s faces by burning him down.” Burning an effigy struck me as an odd way to fundraise for kids, especially given the story I’d heard earlier about Zozobra’s child army. Here might be a good spot to insert the opinions of conspiracy theorists, but in the interest of word count and my journalistic integrity, I will refrain.

I was trying to respect the sanctity of what felt like an ancient rite, but for hours, I’d been berated by “Turn Down for What” and other 2000s Top 40 hits that conjured memories of horny middle school dances in a way that bordered on sacrilegious given the context of what was about to go down. We were moments away from deliverance, and for some reason, I was listening to Ke$ha sing about brushing her teeth with whiskey.

At last, they cut the floodlights in the audience, and we began our final descent. The unmistakable jingle from the Harry Potter motion picture series rang out. Then the “bass dropped”—a dubstep remix of “Hedwig’s Theme” played while performers dressed as Hogwarts students gallivanted around stage for what would turn out to be a twenty-five-minute dance number.

The Fire Dancer appeared in a red unitard and a very tall—probably three-foot—hat constructed to evoke flames with fluttering strips of fabric. She danced and danced. And danced. She teased Zozobra’s ghost feet with her flaming batons, pirouetted to and fro while a live band played instrumental versions of Lady Gaga’s “Bad Romance,” Daft Punk’s “One More Time,” and Billie Eilish’s “Bad Guy.”

Meanwhile, Zozobra groaned and groaned. Incessant howling and moaning droned over the loudspeakers. I learned later this was a live performance by New Mexico District Court Judge William Parnall in the coveted role of Zozobra’s Voice, for which he was one of sixty growlers who auditioned for the part last year.

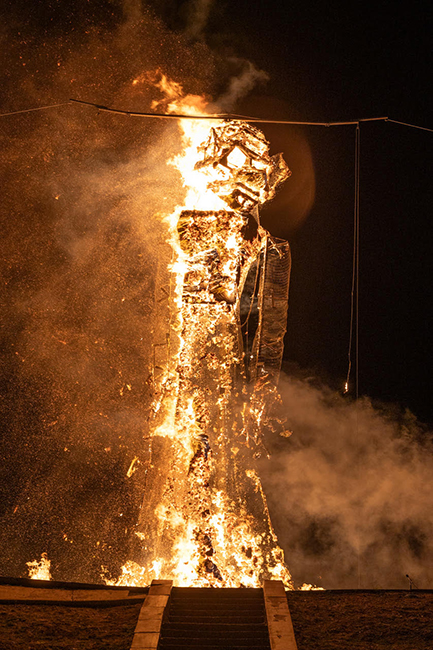

As the story goes, it’s the Fire Dancer who sets off the immolation. But really, it’s someone backstage, though who, exactly, holds the honor of sparking the initial flame is apparently contested. Sandoval had told me he’s the one who “lights the fuse,” while Romero had said he’s the one who “actually takes the match to Zozobra.”

In any case, after nearly half an hour of this musical interlude, someone put the exhausted Fire Dancer out of her misery. They ignited the fireworks that began in Zozobra’s head and traveled down his body. His face glowed from the back with fire, illuminating the whites of his eyes as they darted around frantically. His bottom lip caught flame, and smoke poured out of his mouth. His arms waved back and forth, and he howled.

The beginning phase of the immolation was beautiful and hypnotizing, as large fires are. The later stages were horrifying. His arms burned off and he stopped moving entirely. The groaning ceased. His features had mostly burned away, but he still maintained the semblance of a face. The cavities of his eyes roared with flames. He hung completely consumed by fire.

I’d been taking pictures throughout the course of the night, switching between two lenses. I must have taken 200 photos of Zozobra before the burn. When the fireworks finally went off in his head, I decided to switch my lens one last time.

I took my lens off, but couldn’t get the other on. I tried to put the other lens back on and couldn’t. Incredible.

Hours I’d waited for this moment, and now my camera wouldn’t take a lens. I managed to reign in my anger by telling myself that this checked out with a long tradition of spirits breaking cameras and ghosts wiping whole rolls of film blank. It seemed appropriate. And so I decided to just watch and be present for the incineration of our collective woes.

I was mesmerized by the fire. I’m sure the crowd was cheering. But I don’t remember any noises. In my head it was quiet, and then he collapsed.