Two fires marked Burmese artist Sitt Nyein Aye’s life. After his tragic death in Colorado, a tribute to his “Little Myanmar” of the Southwest.

This article is part of our series The Hyperlocal, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 11.

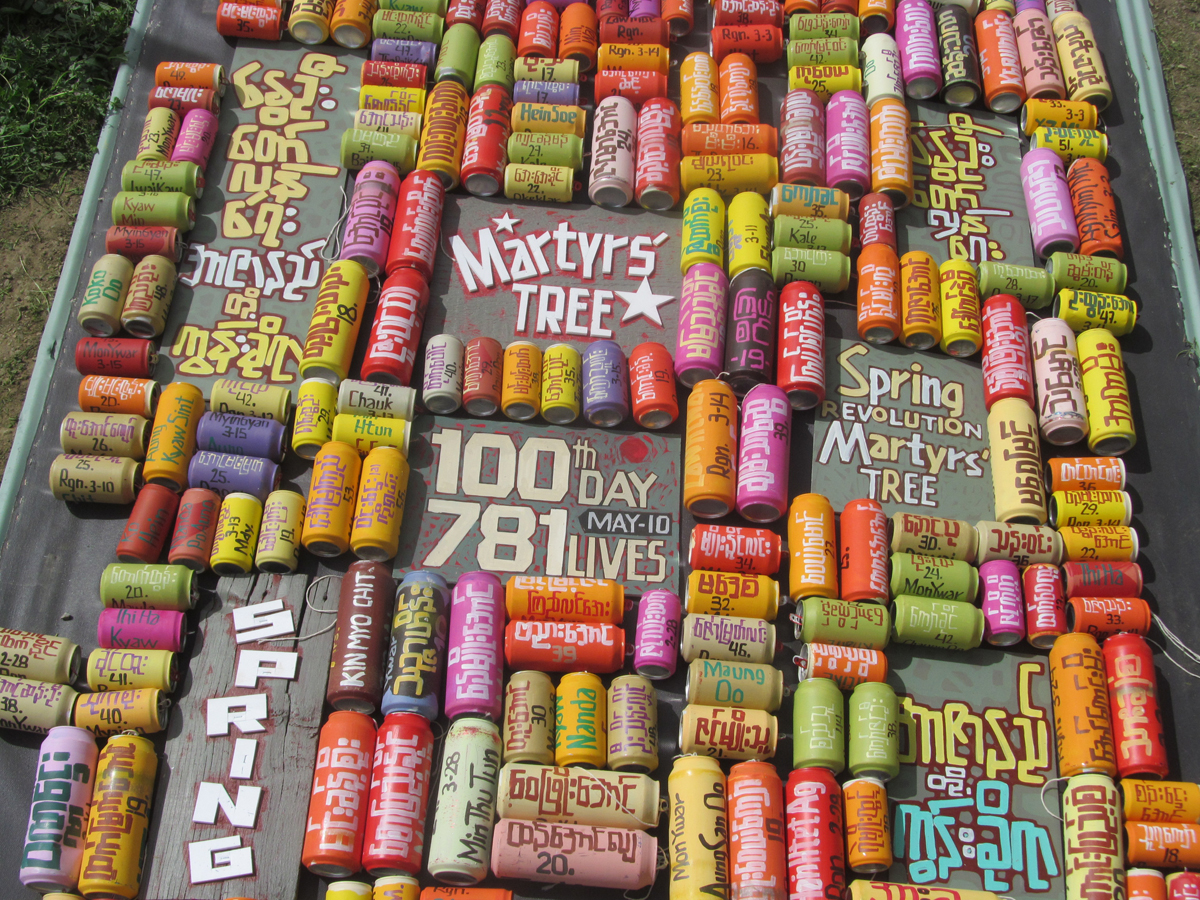

The fire that killed artist, writer, and activist Sitt Nyein Aye, on August 31, 2023, near Trinidad, Colorado, half-consumed a tree neighboring his home. The Burmese exile had dubbed the blue spruce his Martyrs’ Tree and strung its branches with hand-painted aluminum cans bearing the names of fellow activists and artists who have died at the hands of Myanmar’s military dictatorship.

Chaw Ei Thein is a friend of Sitt who shared his status as a Burmese asylee. (The Southeast Asian nation changed its name from Burma to Myanmar in 1989.) She pulls up a photo on her phone from the fire’s aftermath: some of the tribute vessels have popped off the spruce and piled around its trunk, crumpled and singed.

He wanted to be part of the struggle. To be this far away was torturous.

Chaw is a Santa Fe–based artist who has spent the last few years poring over her snapshots from the site, frustrated with the official investigation by Las Animas County. “We were not satisfied,” says Chaw, alleging that “the police looked at the bottles everywhere and said, ‘He’s an alcoholic hoarder.’ They didn’t see it was art.” The cause of death was clear, however: Sitt was “unfortunately trapped” in the house fire, according to the county coroner’s report.

(Disclosure: I curated a solo exhibition by Chaw in 2024, and no longer work at the host gallery.)

Sitt had long felt confined here—not just in the unincorporated community of Jansen, where he lived on the land of a local family who became close friends, but in a country so far from the turmoil at home.

“He wanted to be part of the struggle,” says Chaw, who grew up in Yangon, Myanmar, and as an activist and former law student, intimately knows the many upheavals of the country’s modern history. “To be this far away was torturous. Especially being in such a rural place—it was lonely.”

In Colorado, Sitt transformed his home and studio into a Little Myanmar. Using the vibrant palette of Burmese paintings and textiles, he surrounded himself with imagery and text referencing his homeland and his people’s ongoing struggle to depose the violent junta that controls it. A trailer that he used as a studio reads “The Road to Mandalay,” a reference to a Rudyard Kipling poem, in bubble letters that carry the angular DNA of the Burmese alphabet. The message on the back of the trailer: “Nowhere to Go.”

Sitt’s adopted environment—with its signs, lawn chairs, and myriad found objects, all vibrantly painted—is bifurcated, a zone that flickers between two distant places. As Burmese dissident artists, Sitt and Chaw are part of a diaspora who’ve crafted concentrated versions of their homeland across the Southwest. Their creative methods are both necessarily hyperlocal and forcibly remote.

Chaw sits in her Santa Fe living room, encircled by her own revolutionary artworks. It’s spring, and she’s preparing a major body of work for the 2025 Berlin Biennale, which opened in June. The series of figurative drawings and soft sculptures reconstructs the history of Burmese performance art, a surreptitious protest tradition that led to her brief imprisonment and eighteen-year exile.

Sitt and Chaw are part of a diaspora who’ve crafted concentrated versions of their homeland across the Southwest.

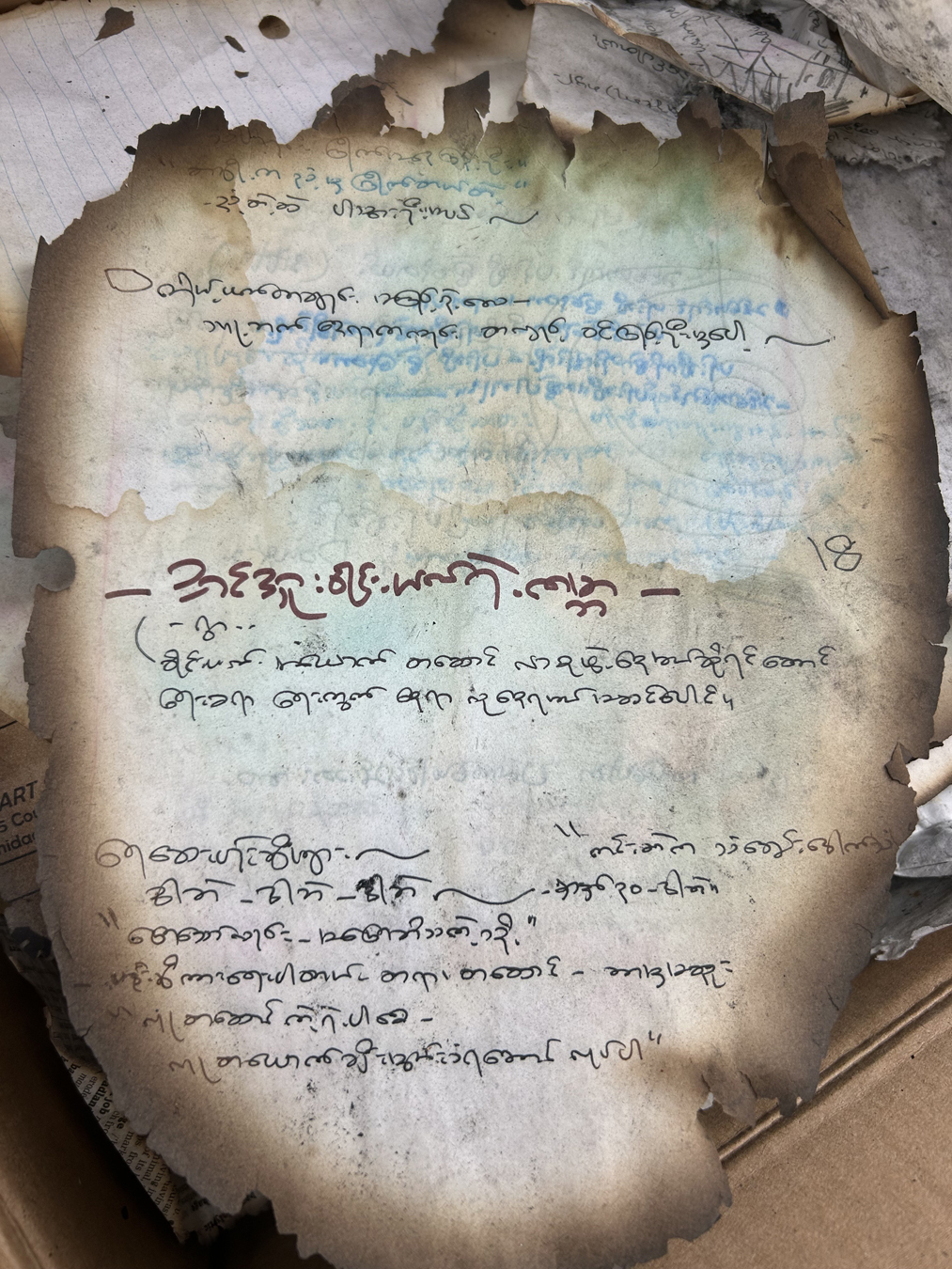

Today, she sifts through another broken archive: sketchbook and journal pages she recovered from Sitt’s home. She recently surfaced details of a formative incident from his time in the city of Mandalay, where he’d escaped small-town poverty to study at Myanmar’s most prestigious art academy. “By the time he turned thirty, Sitt had become a commercial success, opening his own art gallery in 1984 where he sold 200 of his works,” reads an Inter Press Service story from 1998.

Then a massive fire razed the gallery, destroying all of his artwork. “He wrote about that in a piece of paper I have,” says Chaw. “His mother was in the studio at the time, and after the fire, she totally changed—she was shocked, traumatized.”

Sitt had changed his name from Sein Aye to Sitt Nyein Aye—meaning “War and Peace,” after Leo Tolstoy’s novel—in his twenties. In the aftermath of the fire, he was ready to embody its duality, abandoning commercial art to fight for democracy in the 1988 student protests known as the 8888 Uprising. He made cover illustrations and wrote articles and poems for Red Galon, the pro-democracy journal of a prominent Buddhist monks’ organization.

After the uprising, Sitt and many of his collaborators were forced to flee to the jungles of India on the India-Burma border, where he struck up a lifelong mentorship with younger Burmese artist Htein Lin. Later he lived in Delhi, where the Indian defense minister became a major supporter of his work. That’s when he spoke to the aforementioned IPS reporter, characterizing his activist art practice as “gardening” and saying, “I cannot live without doing something [for the democracy struggle]. I have to do something, either painting in thoughts or in reality.”

Chaw and Sitt met a world away in New York City, after he sought asylum in the United States. They connected in 2010 through curator Zasha Colah, who subsequently organized an exhibition of Sitt, Htein, and Chaw’s work, and curated this year’s Berlin Biennale featuring Chaw. In a 2016 interview, Colah called the artistic circle’s work “a survival kit for dealing with extreme political egress. […] Each one of us needs these cultural, mental tools.”

People come to the United States with the American Dream, but not him.

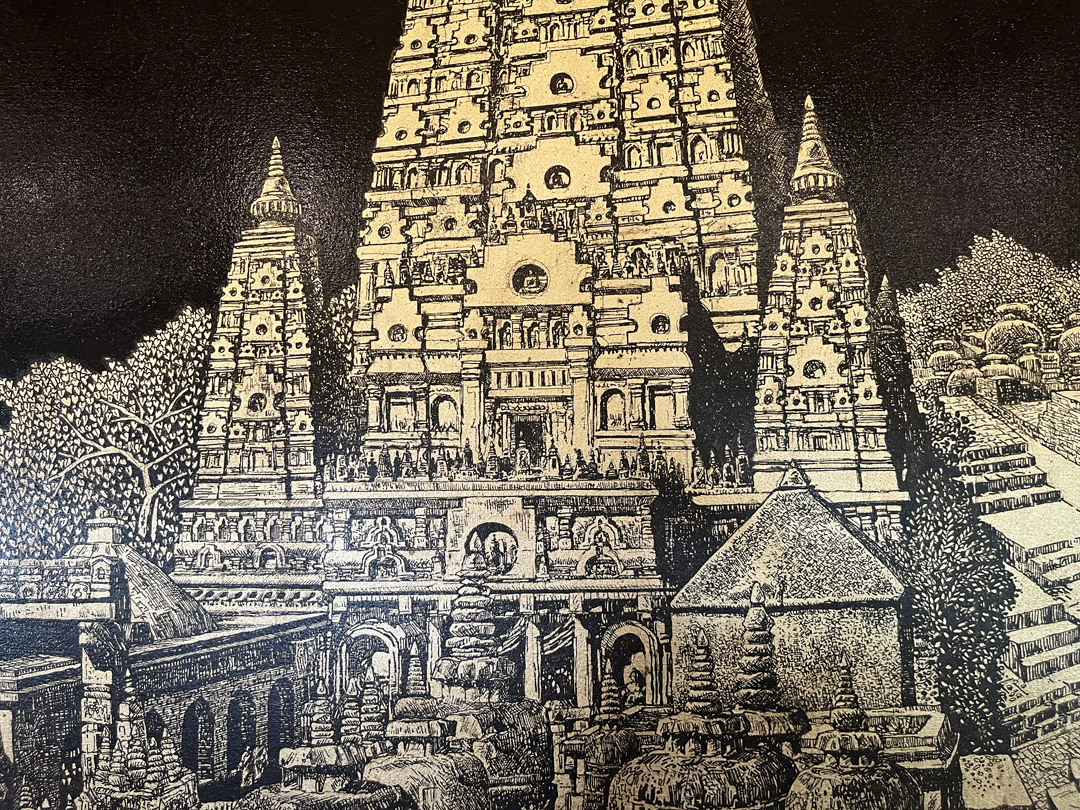

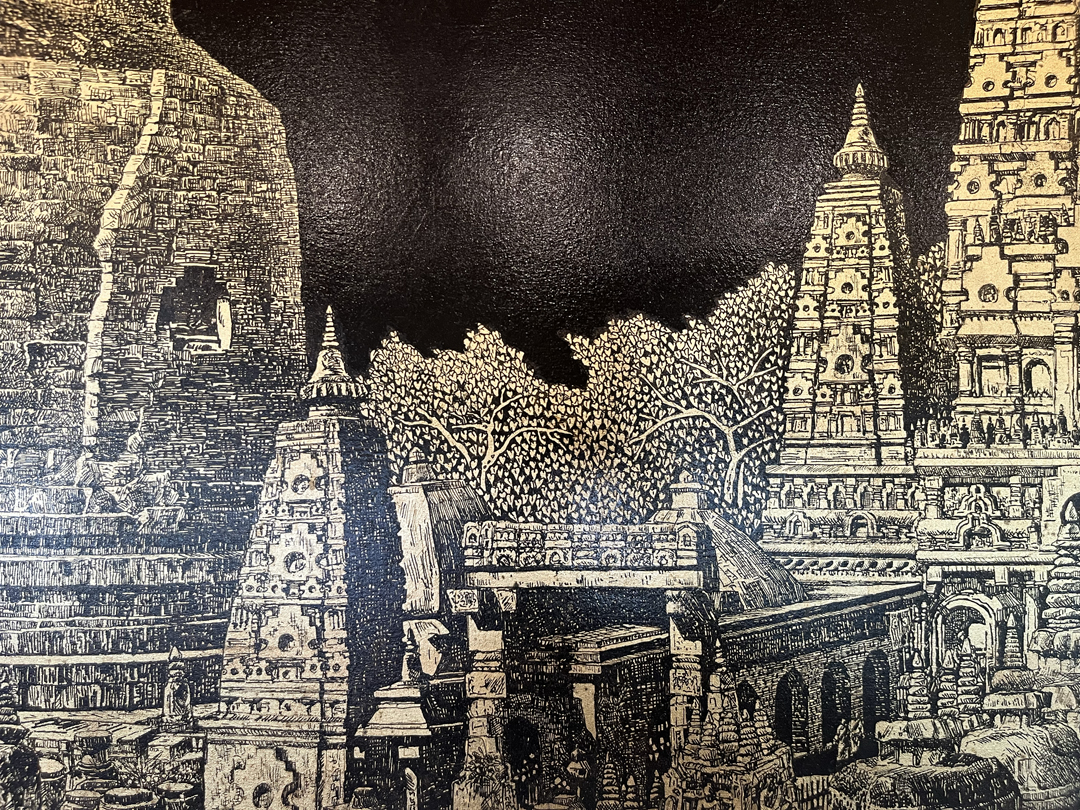

When he arrived in the United States around 2008, Sitt lived at Sitagu Buddha Vihara, a Burmese Buddhist monastery in Austin, Texas, led by Sitagu Sayadaw. The community is another little patch of Myanmar in the Southwest, a sixteen-acre campus crowned by a majestic golden pagoda. Chaw recently made a pilgrimage to the monastery in honor of Sitt, and I made my way there while reporting on this story. We were seeking a multi-panel painting by Sitt that may be his masterpiece, which hangs in the dining hall of the complex.

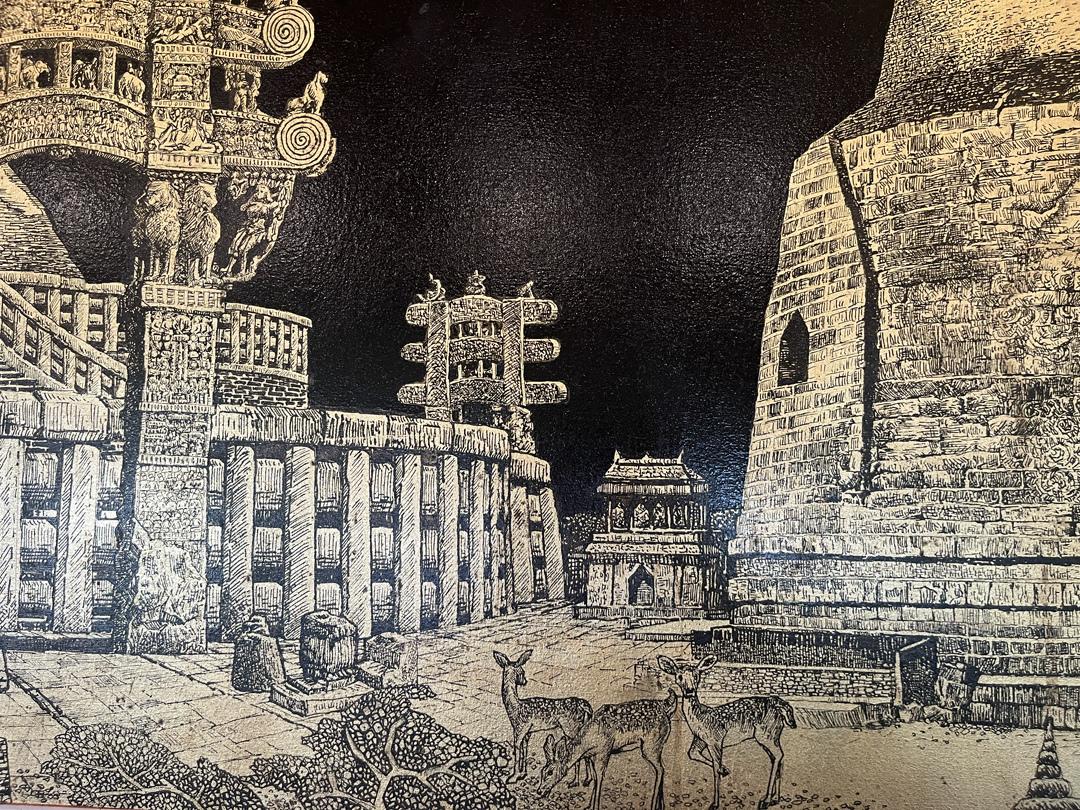

In the large-scale artwork from 2012, thousands of shimmering gold brushstrokes entwine on a black ground, depicting famous Buddhist temples across India in opulent detail. The work feels particularly poignant when you consider the Burmese junta’s treatment of such spaces: since the latest military coup in 2021, the regime has destroyed ninety-four Buddhist religious sites.

“People come to the United States with the American Dream, but not him. He just wanted to be a full-time artist,” says Chaw. “At the entrance of his studio he painted: Designer, Illustrator, Sculptor, Poet, Writer, Journalist, Revolutionary Activist. All his titles.” With every creative skill Sitt had, with every ounce of ingenuity, he crafted vivid portals back home.

Sitt Nyein Aye died in Colorado at sixty-seven years old. His Martyrs’ Tree is still standing—and nearby is a Unity Tree strung with tributes to living friends and family.

Editor’s note: Most Burmese people do not have surnames in the Western sense. The artist’s name is the full phrase: Sitt Nyein Aye. However, he went by Sitt (or among fellow revolutionaries, Ko Sitt) and Chaw Ei Thein goes by Chaw. This is a stylistic choice based on the subjects’ preferences, not a convention.