Artists in The Dirty South at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston work with materials and subject matter that reflect a century-long tradition of regional dialogue between Black visual art and music.

The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse

November 5, 2021–February 6, 2022

Contemporary Arts Museum Houston

A sweeping two-floor exhibition currently on display at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston—which features more than 130 works that range widely across media types and generations—swells the contributions of Southern United States traditions, as well as Dirty South hip hop culture, in an attempt to illustrate its invaluable regional sway on nationwide art and music.

Entering the first gallery of The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse, RaMell Ross’s Caspera (2020) strikingly positions a subject clad in a ghostly black sheet, standing in a wet, muddy field of sand encircled by a woodsy, green backdrop. The apparition recalls lyrics from James Brown’s “Say it Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud” that curator Valerie Cassel Oliver cites in her catalogue essay for the show, “What You Know About the Dirty South?”:

“We’re people, we like the birds and the bees

We’d rather die on our feet

Than be living on our knees.”

Ross’s dark apparition, a walking figure of death with only its feet recognizable as human, interrupts the viewer from interpreting the space as a wooded area common to rural childhoods to confront something more ominous brewing in the bucolic Alabama backdrop. Caspera belongs to a collection of works on the first floor that includes materials from the land, capturing dwellings and everyday Black life in a Southern vernacular.

In the same gallery as Ross’s photograph, Beverly Buchanan’s Unititled (Frustula Series, ca. 1978) concrete structures appear sourced from cast-aside, broken-up building foundations. Buchanan’s oeuvre revisits the idea of space in sculptural assemblages and works on paper capturing homes and other structures—the architectural forms act as embodiments for former inhabitants, real or metaphorical, to find “emotional grounding.”

The cinderblocks in Buchanan’s piece form a throne—the “dirtiness” of the concrete blocks is also found in Earlie Hudnall’s photographs documenting cityscapes, civic life, and nature of Black people in Houston and throughout the South. Hudnall’s works document specific moments and trigger sonic memories of singing in spaces like during childhood play, churches, and social gatherings.

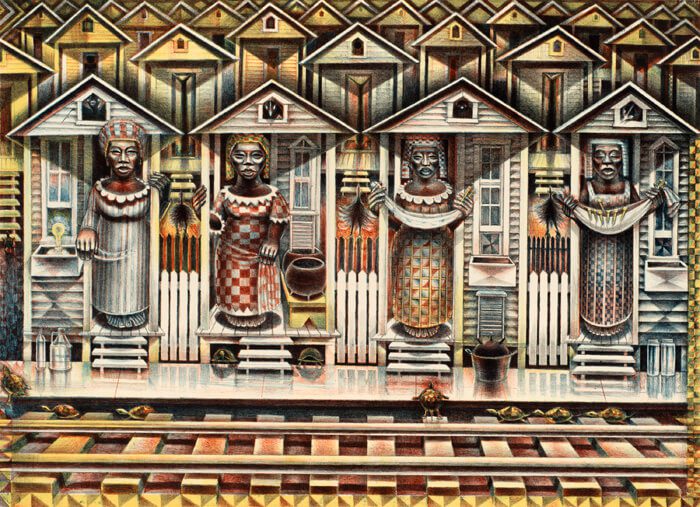

Other galleries in the Landscape section of the exhibition highlight both living artists and historically significant Black Southern artists, including Harlem Renaissance-reared artist Aaron Douglas, folk artist Bill Traylor, midcentury painter Alma Thomas, and Houstonian John Biggers.

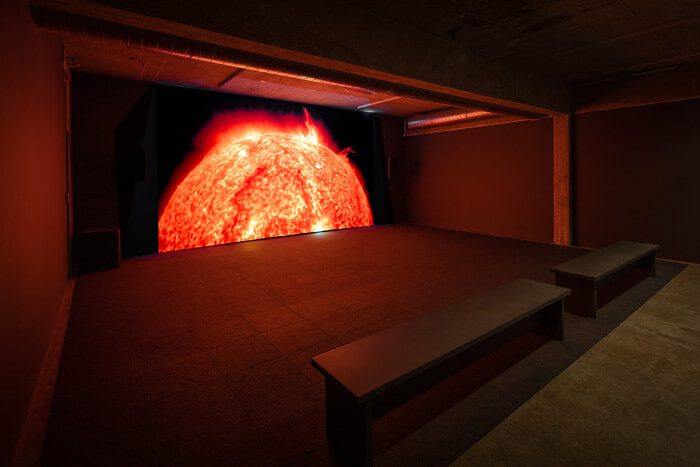

The CAMH show eventually leads viewers to the basement level with the theme of Black Corporeality with works considering bodies of paradigms of performers and athletes alongside the living reality of everyday Black people. Arthur Jafa’s seven-minute video Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016) uses “Ultralight Beam,” a 2016 song by Ye (aka Kanye West), as the backing track to a video montage of archival footage, home videos, and TV clips to celebrate moments of Black excellence and generational pain. Additional standout moments in Jafa’s piece include dance highlights from 1970s television programs juxtaposed with a snippet of Cal Swag District’s song “Teach Me How To Dougie,” a young Biggie Smalls (aka The Notorious B.I.G.) spitting a freestyle on a Brooklyn street corner, and feats of athletic prowess. Throughout the clip, images of a burning bright sun shed a light of truth on a contemporary moment that still reports police abuse of Black adults and children in a legacy derived from the Jim Crow South.

Other works in the Black Corporeality gallery include paintings, found object sculptures, a twentieth-century popular music cabinet of curiosities, and mixed media works that further explore the talent of Black performers and their relationship with mainstream entertainment that lauds their achievements while simultaneously reinforcing white supremacy. For example, Robert Hodge’s Bert Williams (Tapdance) (2013) celebrates African American minstrel performer Bert Williams, the layers of collage paper and black paint suggesting the layers of cork soot Williams would apply to his light complexion to conform to blackface tropes of the minstrel genre.

Leading viewers back upstairs to the second floor, galleries present works that further consider the role of spirituality, from gospel music to Christian ideology, in the Saints and Sinners theme. Works like Rodney McMillian’s Asterisks in Dockery (Blues for Smoke) (2012) recreates a simple Southern church interior in red vinyl, enveloping visitors who walk into the installation with the symbolically laden color associated with blood and life.

From materials culled from the land, like cotton and beans, to improvisational techniques inspired by jazz and hip hop, The Dirty South compellingly asserts the interconnectedness of Black visual and musical expression planted by Afro-Atlantic descendants, rooted in the South, and blooming throughout a larger American cultural landscape.

The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse continues through February 6, 2022 at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, 5216 Montrose Boulevard in Houston.