Five emerging artists explore experiences of the African Diaspora in And Let It Remain So, a Phoenix Art Museum exhibition that assesses family, home, displacement, identity, and Black representation.

And Let It Remain So: Women of the African Diaspora

July 20, 2022–February 12, 2023

Phoenix Art Museum

A girl in a blue sweater stands against an ivory background, her hands clasped beneath a family photograph she holds much like an easel might support a painting. Framed in black, her portrait is set against the backdrop of a blue sea, suggesting the complexities of time and place inherent in experiences of the African Diaspora.

Created by Nadiya I. Nacorda, an artist of Black and Asian descent born in Detroit and based in Virginia, the layered pieces (To have and to hold and Lost in Translation) comprise the first artworks viewers see as they enter the gallery housing And Let It Remain So: Women of the African Diaspora, a recently opened Phoenix Art Museum exhibition spotlighting works by five emerging photographers.

More of Nacorda’s work, which centers on family, is grouped on walls painted in a soft coral pink that calls to the artist’s All the Orchids are Fine series found here. Sleeping Beauty (2015), a photograph that captures an unmade bed in a room where a period bed frame and the art hanging above it suggest histories of colonization, is among them.

Themes of identity, representation, place, land, displacement, home, and family run throughout the exhibition, which is organized by Phoenix Art Museum and the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona. Aaron Turner, an Arkansas-based photographer who also has a curatorial practice focused on photographers of color, curated the show. In 2020, he organized a similar exhibition at Blue Sky, Oregon Center for the Photographic Arts, showing works by three of the five artists included in the Phoenix Art Museum show.

Although it contains more than seventy artworks, the exhibition is hardly a comprehensive survey.

Instead, And Let It Remain So functions most effectively as an intimate study of how these five women—born between 1988 and 1995 and all with significant ties to New York—are exploring and expanding their own diasporan identities through the camera’s lens.

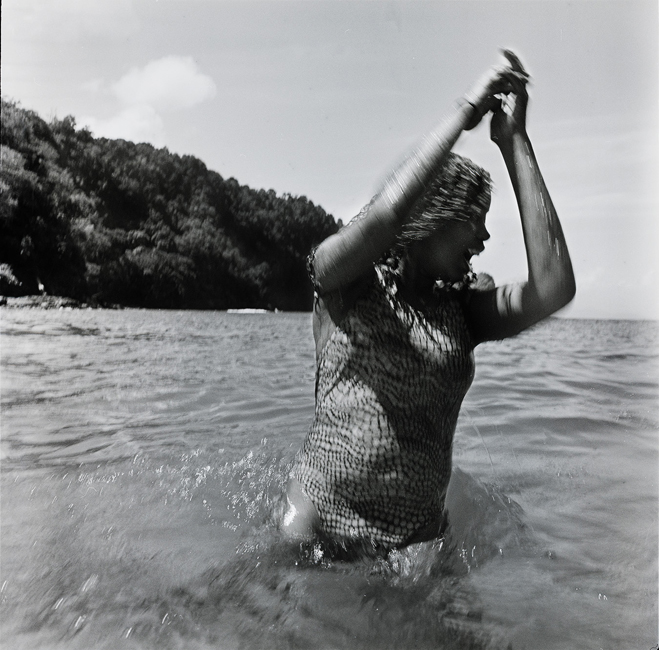

The exhibition includes ten images of friends and community members by Sasha Phyars-Burgess while the artist was in Trinidad and Tobago. The Brooklyn-born artist, whose parents are Trinidadian, is currently based in Pennsylvania.

The subject matter for these photos, all taken in 2013, includes a funeral, a children’s carnival, a woman standing hip-deep in the sea, and more—all documenting cultural specificity while prompting reflection on shared humanity.

The wall forms a playful backdrop for photographs that explore Black identity and interiority, often through figurative imagery and self-portraiture replete with repetition. Cadet’s figures aren’t formally identified, leaving room for viewers to consider myriad possibilities.

In one photograph, viewers see a woman wearing a bathrobe outdoors at night, her face obscured by the bright flash of a camera that suggests both erasure and hypervisibility. In another, fabric resembling that same robe lies cradled between two bright red bougainvillea plants, as if retaining the form of the woman who no longer wears the garment

Cadet’s work boldly calls attention to the issue of representation for Black women, which has historically been so lacking in formal art spaces, while also creating her own narratives to counter those in popular culture.

In another part of the gallery, viewers see portraits and landscapes photographed by Hellen Gaudence, a New York-based artist who also works in her home country of Tanzania.

The large-scale black-and-white photographs feature African migrants she met while attending school in Tucson. Each image is placed within an empty background devoid of cultural context, reinforcing concepts related to loss, displacement, and erasure.

Four smaller color photographs of plants in Tanzania are interspersed among them. Red dirt covering the wild shrubs suggests land left behind, but also the exploration of new ecologies.

Before leaving the gallery, viewers see a final grouping of images by Jasmine Clarke, an artist born and based in Brooklyn whose subject matter includes a board game with four central connected triangles labeled “home.” A man, whose back is covered in sand, calls to mind historical images of enslaved Black men whose backs were disfigured with deep scars.

Water appears again in one of the last photographs viewers see before exiting the exhibition space. Clarke’s Olivia, Looking shows the artist’s sister with green and yellow beaded braids looking out across a gray sea, her back positioned towards the viewer.

It’s unclear whether she’s looking toward the past—or toward the future. Either way, the water suggests movement, implying that her relationships with historical and contemporary diasporan culture will remain ever in flux.

And Let It Remain So: Women of the African Diaspora is scheduled to continue through February 12, 2023, at Phoenix Art Museum, 1625 North Central Avenue.