Cerith Wyn Evans: Aspen Drift at the Aspen Art Museum in Colorado saturates the senses in the Welsh artist’s first exhibition in the States in more than seventeen years.

Cerith Wyn Evans: Aspen Drift

June 11—October 10, 2021

Aspen Art Museum, Aspen, Colorado

Welsh artist Cerith Wyn Evans—famous for his collaborations with Derek Jarman, Tilda Swinton, the Smiths, and Throbbing Gristle—often incorporates sculpture, painting, sound, and light into his shows. Aspen Drift is no exception.

With towering light displays, automated plastic flutes, glass chandeliers, plants stationed upon rotating turntables, looped audio tracks, as well as wall-hanging two-dimensional paintings, the artist leverages multimedia artworks in order to saturate the senses. From June 11 through October 10, 2021, Aspen Art Museum hosts Aspen Drift, Evans’s first States-based exhibition in over seventeen years.

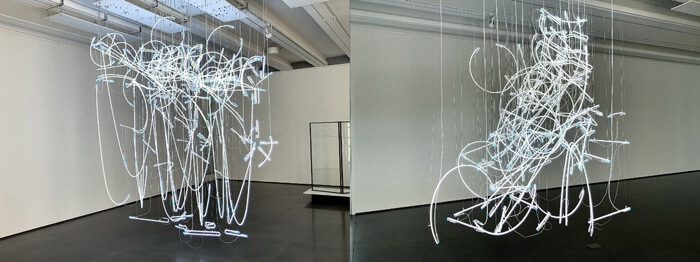

Evans’s large-scale white neon sculptures, or his “drawings in light,” occupy the most prominent space in Aspen Drift. According to the museum’s marketing materials, the two smaller installations—Neon Forms (after Noh, I) and Neon Forms (after Noh, V)—“depict notational diagrams for dancers that come from traditional Japanese Noh theater.” While, as Art Basel’s website notes, Noh theater’s choreology contains “codified, precise movements,” Evans’s hanging neon sculptures embody a more chaotic and complex arrangement with a tangle of overlapping lines and divergent trajectories.

The title artwork Aspen Drift, a massive jumble of neon suspended from the ceiling and extending the length of the second-floor gallery space, is undoubtedly the exhibition’s centerpiece. Unlike the other neon pieces, which are inspired by Noh dance, the larger installation “evokes the feeling of being adrift and also references the snowdrifts of Aspen’s mountainous climate.”

If the frenzied line that gestures toward the natural world sounds (and looks) familiar, it is. In Pedagogical Sketchbook, Paul Klee’s iconic meditation on lines, the Bauhaus mainstay opens his book with a note on the “active line on a walk, moving freely without goal… shifting its position forward”; immediately afterward, he writes of that “same line, accompanied by complementary forms.” He embellishes these notes with corresponding sketches.

The individual neon components of Evans’s artwork bear a striking resemblance to Klee’s wandering line; and the interaction of Klee’s accompanying lines appear as prescient harbingers of Evans’s neon sculptures in aggregate form.

Of course, as Pedagogical Sketchbook progresses, the author draws a conceptual line from the initial drawings to structural concepts in nature, such as the skeletal and circulatory systems. From there, he advances the idea that the line is a fundamental component of earth, air, and water. The book concludes by offering a framework for the relationship between the line and the metaphysical, insofar as Klee claims that the line’s final stage passes “on to infinite movement, where the actual direction of movement becomes irrelevant” and “the question is no longer: ‘to move there’ but to be ‘everywhere’ and consequently also ‘There!’”

Indeed, one of the beauties of Evans’s Aspen Drift resides in the fact that it too passes into the infinite realm; or, at very least, simultaneously reaches for both the “everywhere” and the “there.” To begin with, the soft light that emanates from the neon sculpture illuminates the gallery space in a dull glow; thus, the artwork escapes its immediate, physical confines of glass tubing and extends outward into the room.

But more than simply producing multivalent light waves that extend the line in infinite directions, Aspen Drift proliferates through an endless series of reflections. The sculpture doubles itself in the buffed surface of the concrete flooring, and, as the spectator moves, so too does the blurred, ghostly reflection. Furthermore, Aspen Drift replicates in the dozen or so toughened low iron glass panels that comprise the sound installation Pli S=E=L=O=N Pli situated at the other side of the room. The white neon light even escapes the gallery space through reflections on the clear glass exit doors that open into the Aspen Art Museum’s second-floor corridor.

Evans’s white neon sculpture Aspen Drift proposes “a solution of kinetic infinity” that Klee calls for in Pedagogical Sketchbook: its lines wander, accompany one another in complementary forms, mimic organisms and our elemental surroundings, and then multiply into infinity.