Black artists imagine radical futures through hope, healing, and history in Reclaiming Hope: Afrofuturist Visions at Tempe Center for the Arts.

This article is part of our Radical Futures series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 10.

TEMPE, AZ—Alanna Airitam, a Tucson-based photographic artist whose work explores the hidden histories of Black Americans, remembers going to museums as a child but never feeling like she saw herself in the portraits and still life paintings that surrounded her. “I wanted to reframe those stories and histories because we were there, and we weren’t always in servitude although that’s how we’re often portrayed,” she says.

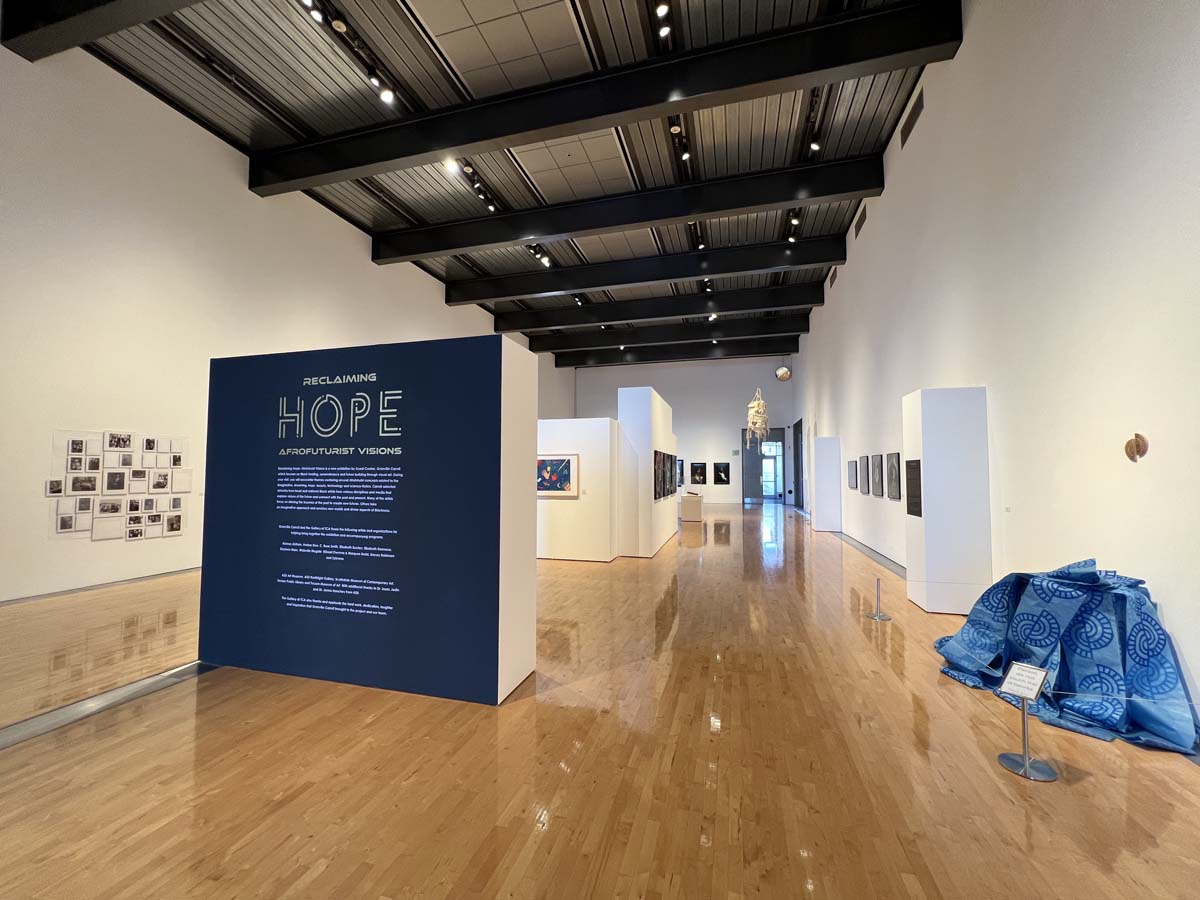

Today, her work is part of Reclaiming Hope: Afrofuturist Visions, an exhibition that foregrounds Black voices as they reimagine radical futures while exploring themes such as beauty, hope, technology, and science-fiction.

The exhibition was curated by Granville Carroll, a Mesa-based photographer whose work is also featured in the show. It opened on September 21, 2024, and runs through January 4, 2025, at The Gallery at Tempe Center for the Arts, a venue located just southeast of Phoenix, Arizona.

Carroll conceives of Afrofuturism as “a particular framework for Black liberation through imagination and future building, which is often filtered through science fiction, spirituality, or religion,” adding that Afrofuturism “redefines Black identity so it’s not rooted in negative social constructs that are harmful for the community.”

For this show, Carroll highlights more than a dozen artists, including C. Rose Smith, Wabwila Mugala, and Elizabeth Denneau, whose media include not only photography, but also sculpture, painting, prints, textiles, video, mural art, and more. “I wanted to include diverse artworks that really showcase the various dimensions of the Black voice and Black artists, and I wanted to focus on artists working in Arizona,” he explains.

For Tucson-based artist Amber Doe, the very presence of this exhibition in Arizona is significant, particularly in the context of histories that identify the first non-Native resident of what would become America as an enslaved African man named Esteban, who arrived in the Southwest during the 16th century.

“Arizona is physically such a large land mass, but the population of African Americans and African American artists is incredibly small,” reflects Doe. “I think about the fact that there has been an African descendant presence in this area for so long, but we’re not able to see this in most spaces.”

Four of the artists, including Airitam and Doe, are part of the Southwest Black Arts Collective based in Tucson, Arizona. Some, including Betye Saar and Kara Walker, are internationally renowned. “Aside from myself, most of these artists don’t label themselves as Afrofuturist, but they work in conversation with these larger themes and ideas, including hope and healing,” reflects Carroll.

Throughout the gallery, exhibited works channel the vast array of methodologies, materials, and ideas that contribute to the expansive nature of Afrofuturism in contemporary art.

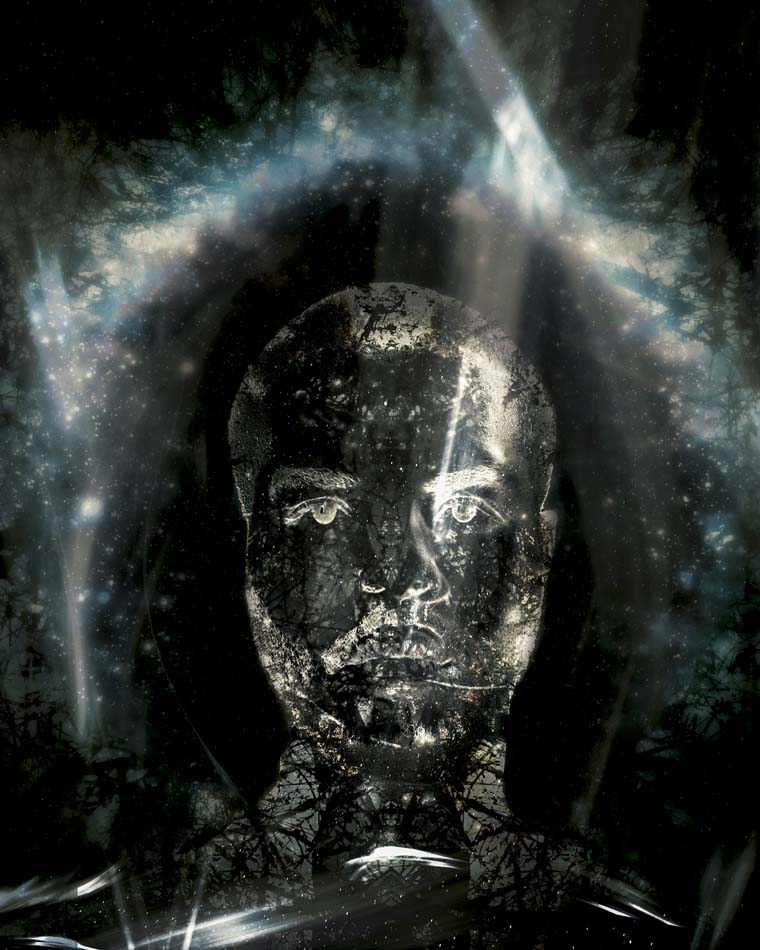

Five of Carroll’s photographs from his ongoing In the Finite, Infinitely series launched in 2020, for example, manifest his focus on ontological concerns such as the fluid or multidimensional nature of time, which he conceives as spherical rather than linear. Most ground an abstracted human figure in an expanse of stars and other matter, suggesting the cosmological context for explorations of Black identity, beauty, and power.

Meanwhile, five of Airitam’s photographs from her 2017 series The Golden Age speak to the prevalence of examining and critiquing history in Afrofuturism, while reflecting the artist’s own creative practice as well. “My work is rooted in history but also forward-looking,” she explains. For this series, Airitam couples portraiture and still life imagery reminiscent of Renaissance paintings in photographs of friends and fellow creatives, alluding to art history as she considers the complexities of discerning what’s real or true, as well as the nature of Black representation. “I feel like I’m always working in Afrofuturism, although I don’t necessarily use the term,” Airitam adds.

For every artist, the gallery has posted a comprehensive text panel that includes helpful context for understanding both their larger body of work and how their work in this show relates to Afrofuturist perspectives. In this way, viewers discover that several of these artists focus on the experiences of Black women, the African diaspora, and family histories.

The materials and processes these artists use point to the specific ways they are reimagining radical futures while amplifying Afrofuturist themes.

With her salon wall-style grouping of images, for example, Tucson-based artist Elizabeth Burden seeks to “create a new archive of Blackness.” And Doe, whose two textile works in the exhibition reflect her view of material as metaphor, uses cotton to reference “the industry’s implicit engagement in the slave trade” while also “reclaiming this material” for new possibilities.

Concepts of community and co-creating are evident as well.

Carroll worked with Michelle Nichols-Dock, senior visual arts curator for Tempe Center for the Arts, to transform a gallery nook into a “Funk Lounge” complete with seating, plus books and albums that embody Afrofuturism. “It’s meant to give people rest and a space to learn more about the topics in the show,” says Carroll.

Along a wall of windows near both the gallery and an adjacent lakeside park, people see Stacey Robinson’s Afrofuturism-themed mural Let Us Reflect Us. The gallery will host related programming, including an artist panel moderated by guest curator Granville Carroll and scholar Jenna Hanchey, during the exhibition’s run.

Given Airitam’s childhood memories of seeing countless portraits and still life paintings that felt disconnected from her own identity and personal agency, Airitam clearly hopes the Reclaiming Hope: Afrofuturist Visions exhibition will resonate differently for those who see it. “This is our power. All of us are amazing, powerful people,” she says, before elaborating on her hopes for the exhibition’s impact.

“The work is to remind all of us – no matter our race, gender, or background – that every one of us has a birthright to meet the full potential of our best selves without the interference of others,” Airitam adds. “I want people to walk into that space and not think of it as ‘other.’ It’s not just about being Black. It’s about our collective future, and we can all find ourselves in that space.”

The Reclaiming Hope panel talk moderated by curator Granville Carroll with scholar Jenna Hanchey will take place at The Gallery at TCA, from 6 to 8 pm on Thursday, November 14. Panelists include artists Alanna Airitam, Elizabeth Burden, and Elizabeth Denneau.