OKLA, Ed Ruscha’s first solo exhibition in Oklahoma where he grew up, is not just a homecoming parade for the artist, who is still making work at eighty-three years old.

Ed Ruscha: OKLA

February 18–July 5, 2021

Oklahoma Contemporary, Oklahoma City

In Ed Ruscha’s 1975 short film Miracle, an auto mechanic (artist Jim Ganzer) opens a bag of Wonderbread to make a tuna fish sandwich. A bombshell blonde (Michelle Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas) competes with a red ’65 Mustang for his attention. While these obvious American tropes keep the viewer from asking too many questions—after all, this must be about style—the mechanic’s clothes inexplicably become cleaner over time as he works, the soil from his coveralls lifted by some kind of Hollywood formula.

Reliance on iconography as distancing material is a cornerstone of Ruscha’s work. He’s kept a long lens on the City of Angels for more than sixty years living and working in LA. Now he’s taking another look at the place where he’s from. The Miracle film appears in a landmark exhibition called OKLA, which reintroduces the Los Angeles pop art superstar as a child of Oklahoma City. OKLA will serve as entry to the new Oklahoma Contemporary Arts Center for many visitors since the Whitney-like building, with its money views and wavy interior shapes, debuted quietly last year during the first wave of pandemic-related cancellations. Too, though, this mining of Ruscha’s formative years in the heartland will be remembered as a milestone in the region’s quest toward artistic and cultural awakening: OKLA is the first solo exhibition of Ruscha’s work in the city and state where he lived from age five until he made the drive West for art school at eighteen in 1956.

We learn in the exhibition how the expanses of Oklahoma appear in Ruscha’s work even when Los Angeles is the object of his reserved humor and pointed nostalgia. Before he photographed Every Building on the Sunset Strip for the 1966 book of the same title, he had the impulse to do a cataloguing project of that kind in Oklahoma, says co-curator and Ruscha scholar Alexandra Schwartz, who points to Ruscha’s quaint OKC visage House on 38th Street painted in 1965. The artist’s doting attention to changing streets continues with his regular updates to the LA series. That sensibility is connected to his love of fonts and pithy text, it turns out: Ruscha brought the world to his neighbors on routes as a paperboy in OKC and read the comics every morning.

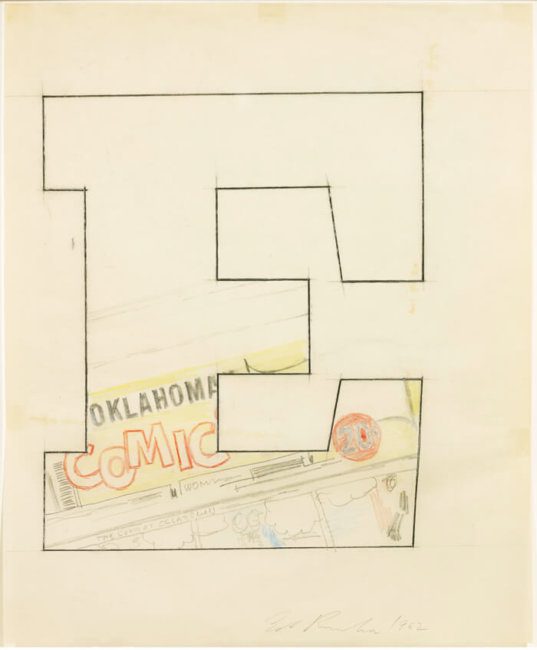

A woodcut portrait of the artist’s mother Dorothy hangs near Ruscha’s self-defining 1962 Oklahoma-E. Co-curator and Oklahoma Contemporary artistic director Jeremiah Davis beamed during a preview at the artist’s drawing of a serif letter E in the same font that used to sit atop The Daily Oklahoman’s comics page. The Contemporary put it on a short run of t-shirts.

Thankfully, OKLA is not just a hero’s parade for Ruscha, who is still making work at eighty-three years old and has begun to grapple with the limits of his genre’s ambiguity. Ruscha kept some drumskins he found at a leather store in LA for almost fifty years before imbuing them with text. Two of these pieces appear in this exhibition: No Harm (2019) and I Didn’t Do Nothing About It (2018). Ruscha tells a story about the Native dancers he saw in Oklahoma as a kid, their American football jerseys peeking out from under ritual dress as they played their drums. The effect of seeing phrases like “I never done nobody no harm” in red—in a font named “Boy Scout” by the artist—on these surfaces, is much more chilling than the multicultural narrative would suggest. These works move toward a much-needed reckoning with white violence, even if Ruscha doesn’t address the dissonance.

Visitors see another uncharacteristically political work of Ruscha’s before they view anything else in the Contemporary’s indoor galleries. Our Flag (2017), an image of a tattered American flag in the wind, looms large above the front desk in the lobby. The original painting hung at the Brooklyn Museum when it served as a polling place in the 2020 presidential election. Ruscha asked the curators if they might want it and ended up offering a digital reproduction. One can either see what’s left of the proud flag, what’s been ripped out of it, or a symbol that used to be clean, at some point way back, and never will be again.