Byron T. Seeley of Monk King Bird Pottery makes the most of his time making and selling art in a former uranium mine boomtown with a current population of twenty-two.

JEFFREY CITY, WY—“You can write about me, but it’s been done,” the potter Byron T. Seeley tells me as I pull out a notepad in Monk King Bird Pottery, his studio and store, which he lives next to off Highway 287 in Jeffrey City, Wyoming.

It’s true. Last year, Wyofile wrote a short profile on him, and, occasionally, someone comes to snap his photograph. One portrait of Seeley and his dog, made by the artist Eric Krszjzaniek, hangs above Seeley’s stoneware. (Krszjzaniek’s photography, including this piece, was exhibited at the 2022 Governor’s Capitol Art Exhibition. From September 15 through mid-November 2023, he has another photography exhibition, Absence/Presence, at the Biodiversity Institute in Laramie featuring images of Jeffrey City and Seeley.) Additionally, Seeley is famous in the nearby town of Lander, where he used to have a shop and where local businesses proudly display his pottery.

Yet, despite local interest in him as an artist and muse, internet searches provide scant documentation of Seeley beyond some travel blog posts and YouTube videos, including one where he takes “pot shots”—shooting his work with a gun. You also won’t find much information about Jeffrey City, the former uranium mining town in central Wyoming that boomed in the 1950s and busted in the 1980s, holding onto a paltry population of twenty-two.

Despite his modesty or ascetic reluctance—either is feasible for the presumed religieux of Monk King Bird Pottery—he begins by telling me about his apprenticeship with Bridgit Hauser in Austin, Texas, in the 1990s. He opened his shop in nearby Martindale a few years later before moving to Taos, New Mexico, in the late ’90s. Ultimately, he got pushed deeper into Wyoming due to the high cost of living elsewhere. For the past sixteen years, he’s anchored himself in Jeffrey City, buying his property for its affordability and proximity to the highway, which gives him visibility to travelers.

“The name came from a misspelling,” Seeley informs me as we stand outside, reflecting on his extravagant signage. “They were filming A Perfect World—that Clint Eastwood movie—[in Martindale],” Seeley says. “One of [Eastwood’s] security guards told me I needed to brand myself, and I told him I was thinking about Mockingbird Pottery because I like the local mockingbirds.”

The day after the film crew left, Seeley found a handpainted sign in front of his shop—MONK KING BIRD POTTERY—and immediately adopted the malapropism, adding the tagline, “Don’t mock me, monk me!” to his business card.

“What happened to the sign?” I ask.

“When I moved to Casper, [Wyoming],” Seeley answers, “I put it into storage. Do you know the show Storage Wars? That’s probably what happened. The whole unit was sold at auction. But really, I lost it because of alcohol.”

One of the signs that greets you when you cross Monk King Bird’s threshold reads “ALCOHOL FREE ZONE.” Seeley credits his six years of sobriety to his mutt, Floyd. After tripping over him and breaking an ankle, he was hospitalized and found teetotaler resolve, realizing he didn’t want to abandon his mother and sister after they already lost his father, another sister, and a brother due to various tragedies.

Only a few abstract paintings displayed in his shop remind him of his drinking days, so he no longer paints. In his words, he has to be “in a crazy, party state to paint.”

“Are they for sale?” I ask.

“Sure. I told one guy I’d sell him one for $2,000 because that’s the only price I’d be willing to part with it for.”

Additionally, he will part with some of his prized Wyoming jade for the right price—a very high price since the collection also sustains his ongoing sobriety. “I replaced alcohol with jade,” he imparts as he takes an unpolished, unimpressive hunk of rock out of a safe. After shining a flashlight on it, though, it glows a covetous bright green.

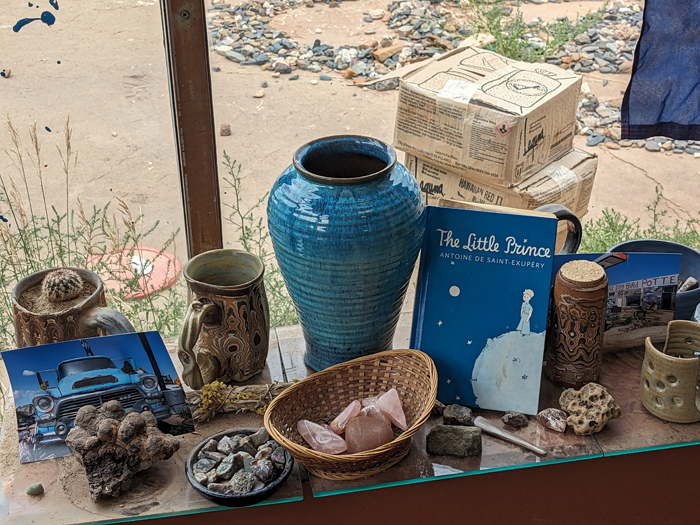

Of course, the focal point of Seeley’s shop is his pottery, which he makes by mixing various clay colors. After spinning an amalgam on his wheel, he uses a tool to strip a thin layer off the surface, revealing uneven red, brown, white, and black stripes, resembling petrified wood. He also has a collection of “pot shots,” including “shot shot glasses,” which he shoots with a pellet gun while they remain wet and unfired.

“I’d prefer to use a .22, but I can’t [because I went to jail for selling marijuana]. I want to get a black powder gun to get bigger holes.”

Seeley also isn’t shy about his jailbird past, displaying a series of for-sale “Byron’s Jail House Doodles”—abstract ballpoint pen designs he made during his several months in Fremont County Jail.

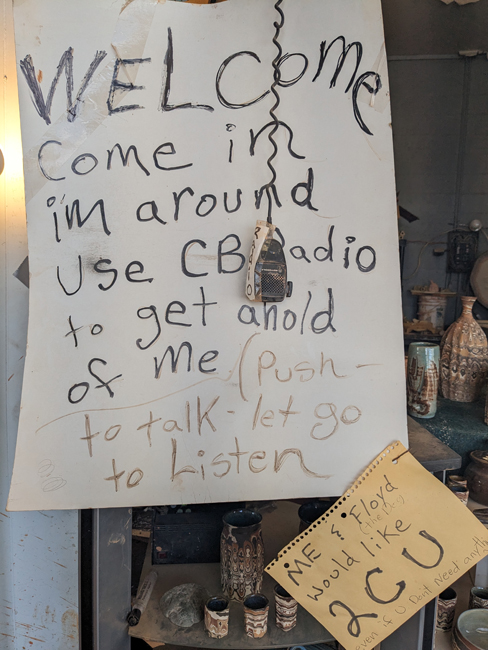

A travel trailer pulls into the parking lot. “They must be out of gas,” Seeley observes. Occupying a former gas station, Monk King Bird’s lot includes a canopy with no pumps. Ironically, an abandoned-looking garage across the street boasts an inconspicuous, serviceable gas pump, which Seeley directs desperate travelers to.

A married couple on a road trip from West Virginia disembark their RV, surprising Seeley with their interest in local curiosities. They leave with one of Seeley’s mugs.

Sometimes passersby mistake Seeley’s shop for a restaurant since one of his signs reads “Home of the Primordial Soup Dish.” The dish, in fact, is a plate he makes using the same multi-clay technique as his mugs. “They’re my Moby Dick,” he jokes, admitting that he has none for sale due to the difficulty of stripping the surface layer and polishing the clay with steel wool without puncturing it.

During our interview, more people than you might expect visit Seeley, including a young man from Lander dropping off clay. Since Seeley cannot leave the county without violating parole, he relies on others for materials from Denver, a four-and-a-half-hour drive away. Moreover, as with this young man, Seeley will trade his pottery for clay.

Another visitor comes bearing rocks he found in the area, requesting Seeley’s help identifying them. Although Seeley denies geological expertise, he sells other people’s scavenged gemstones and minerals, such as “Dino Poo,” fossilized feces known as coprolites. Friends also trust Seeley to appraise their findings from the foothills visible to the north of his property.

Grabbing his flashlight and magnets, Seeley and I go out to the man’s car. After a magnet stuck to the side of a heavy, black rock, Seeley deems it nephrite, less valuable than jadeite.

Once the gem hunter leaves, I ask about Seeley’s plethora of photographs, collages, and paintings. Seeley’s late neighbor and friend, Charles Erickson, a proud libertarian, gifted Seeley several paintings from his Utopia series, depicting wide-eyed, unclad people staring with horror upon an undisclosed communist paradise.

“And this one?” I inquire, pointing to an abstract painting.

“That one is called Eternal Spermazoa,” Seeley beams about the work that his friend, Casey Massman, painted while attending Lander High School.

A Wyoming native himself, Seeley went to high school in Big Piney, which spawned his love for ceramics. While a student, he was also the janitor with keys that gave him 24/7 access to the art room. Pottery saved Seeley from becoming a true cowboy, riding a horse as a ranch hand for hard work and little pay like his father and grandfather. At one point, Seeley proudly directs my attention to his grandfather’s Wyoming Cowboy Hall of Fame medal.

Pondering the mascots and monikers surrounding Seeley—cowboy, mad potter, jailbird, abstinent monk, and muse—he strikes me as best represented by a tumbleweed–blown into one dusty Western town after the next, attracting interest and curiosity. In a similar vein, Seeley reminds me of the Dude from The Big Lebowski (1998), which opens with the song “Tumbling Tumbleweeds,” following one of the sagebrush before introducing us to the film’s protagonist, a Gen-X hippy with a zen-like level of chill. While Seeley’s equanimity makes him guru-like, and perhaps also fails to shield him from the hyperbolic chaos and evil of the world according to the Coen brothers, he certainly doesn’t share the Dude’s lazy lack of production. And, you can’t placate him with a white Russian.

You also won’t find him bowling, although one of the abandoned buildings in Jeffrey City possesses a faded bowling alley sign. If you walk around the almost-ghost town on the other side of the highway from Monk King Bird Pottery, watching someone mow their lawn next to a crumbling, abandoned apartment complex erected, perhaps, seventy years ago, it doesn’t take long to sympathize with Seeley’s lonely travail of isolation.

“What are the winters like here?” I ask nervously.

To my relief, Seeley shuts down his shop to live with his mother in Lander since frequent highway closures deter customers and make business impossible.

“In the spring, when the wind stops blowing, and it’s not too hot—it’s paradise,” Seeley says, smiling and surveying the golden August tundra.

If you happen to find yourself in this ephemeral paradise, on the summer road between Rawlins and Lander, pause in Jeffrey City, and meet the man who monked himself amid his beautiful stoneware.