David Richard Gallery

March 23 – May 26, 2018

Michael Hedges is a painter based near Chicago. He is youngish, what we might call “mid-career,” and I would suggest that he’s an artist to watch as he continues making art over the years. In Bloom consists of fifteen oil paintings whose style and process seem to reflect an ardently informed education in the history of post-war abstraction, also known as the New York School and Action Painting, heroically embodied by mythic rivals Jackson Pollack and Willem De Kooning. Hedges is well versed in the tenets of mid-twentieth-century Modern painting, and has thoroughly absorbed the lessons of the push-and-pull of paint and dimensionality on a flat surface, as taught by Hans Hofmann, who was informed not a little by the pre-cubist works of Paul Cézanne.

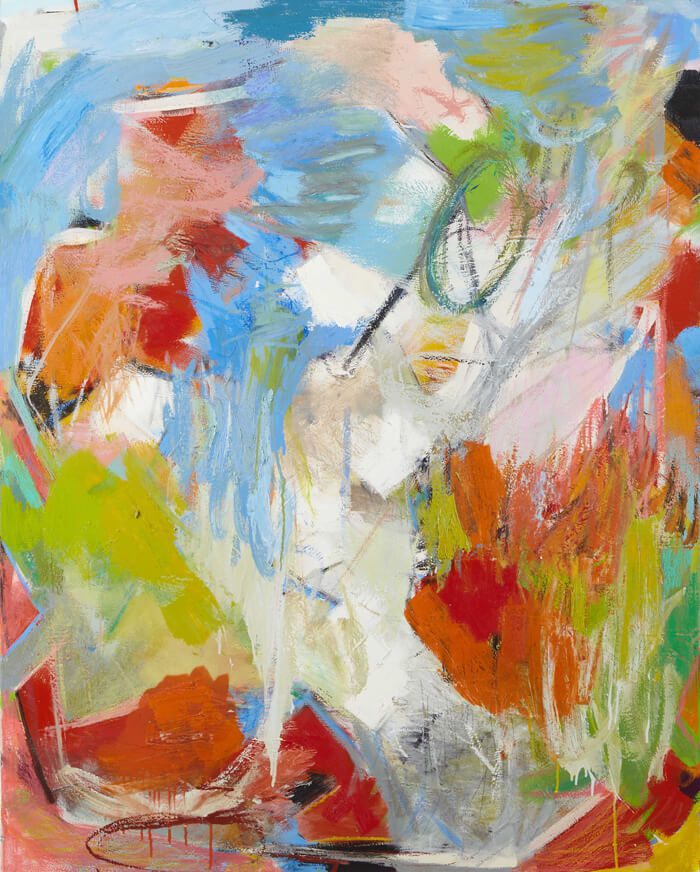

The exhibition consists of both paintings on primed canvas and untreated linen. Richard Barger, one of the co-owners of the gallery, made an observation terrifically relevant to that fact: the canvas pieces seem to emit light from within the pigments themselves, while the linen works absorb pigment and, therefore, light. The difference is subtle, but can’t be unseen once the viewer becomes aware of it. In the lobby of gallery, the canvas titled Barefoot Dreaming occupies prime real estate with self-assurance; its saturated colors make it the perfect choice for tempting window shoppers. Thanks to careful lighting with white LED bulbs throughout the show, Hedges canvases are shown in optimum conditions. On the back wall, In Bloom shines into the room with the brio of a full moon. The complementary canvas Moonbeam confirms that Hedges is decisively a colorist. The blues and oranges of both canvases dance with a degree of movement that surpasses the struggle for dimensional dominance you’d expect of Hans Hofmann’s paintings. When I approached the canvas Encouraged Rumors from its right-hand side, I noted passages that look Cézanne-esque, like the houses of Mont Sainte Victoire which he painted over and over.

Together, the linens and canvases dialogue about the palette knife versus the brush, and about mark-making versus the action of painting. The linens often encompass collage, intimating that they might consist of sections of larger paintings that have been cut up and pieced together. While I enjoyed the play of two-dimensionality that the linen collages offer in comparison with the painted and primed canvases, I sometimes found that pigment had faded into the material just a bit more than might have been optimal. For example, Dreams fadesinto itself to the point of nearly getting lost. Because the linens haven’t been under-painted, they suggest the stain paintings of Helen Frankenthaler. As Barger pointed out, the linens are much more subdued and darker in palette, which I found suggested older, mid-century work.

The exception that proved the rule, Assembled Materials looks like it could have come straight out of the 1950s or ’60s, with its tones of red and russet. Upon initial inspection, the canvas bore some characteristics of Red Mesa, a work on linen, at least in terms of form and color. Red Mesa looks juicy at first glance, then becomes a very arid red-rocks scene as the paint goes from globs to almost completely gone—absorbed into the linen. Although it isn’t revealed immediately, the surface includes a collaged pocket shape that looks like it came straight off of a tee shirt. It’s an engaging piece, and seems right at home in drought-afflicted Santa Fe.