Tracing their deep roots in New Mexico, the founders of Maida Goods and / shed reclaim daily life as an artistic, spiritual, and historical practice.

Industrialization and façades of progress have attempted to render work and life, people and nature, past and present as silos devoid of historical context. Maida Branch (Ute, Pueblo, Genízara) and Johnny Ortiz-Concha (Taos Pueblo/Hispano) are redefining life, work, and art as spiritual practices interwoven with the land and people they come from.

The day before my interview with Branch and Ortiz-Concha, I walked through the sagebrush near my house, mind latticed with crystalline glimmers of information gleaned from recuerdos (memories) published on the / shed website. On the fragrant trail, I realized how what they share of their lives nudges me towards a daily existence laden with more intention.

Branch’s multidisciplinary project Maida Goods is “a love story, a coming home story,” an extension of herself—living, breathing, ever-evolving. What started as an artist collective between her, silversmith Gino Antonio (Diné), and ceramicist Camilla Trujillo has flowered into nine artists and a studio where Branch is free to create what’s meaningful to her. / shed is Ortiz-Concha’s “ongoing meditation” and “ecosystem of practices” centered around small-scale dinners, or recolecciones—the manifestations of creative processes influenced by their physical and cultural origins.

After first visiting Taos in 2021, I kept hearing about / shed. Ortiz-Concha had cut his teeth in kitchens like Michelin-starred Alinea in Chicago and Saison in San Francisco. Now, he was flipping off—and on its head—the commercial elements of fine dining, while still paying respects to his mentors via intimate dinners reflecting what he’s learned, expressed through his Native terroir.

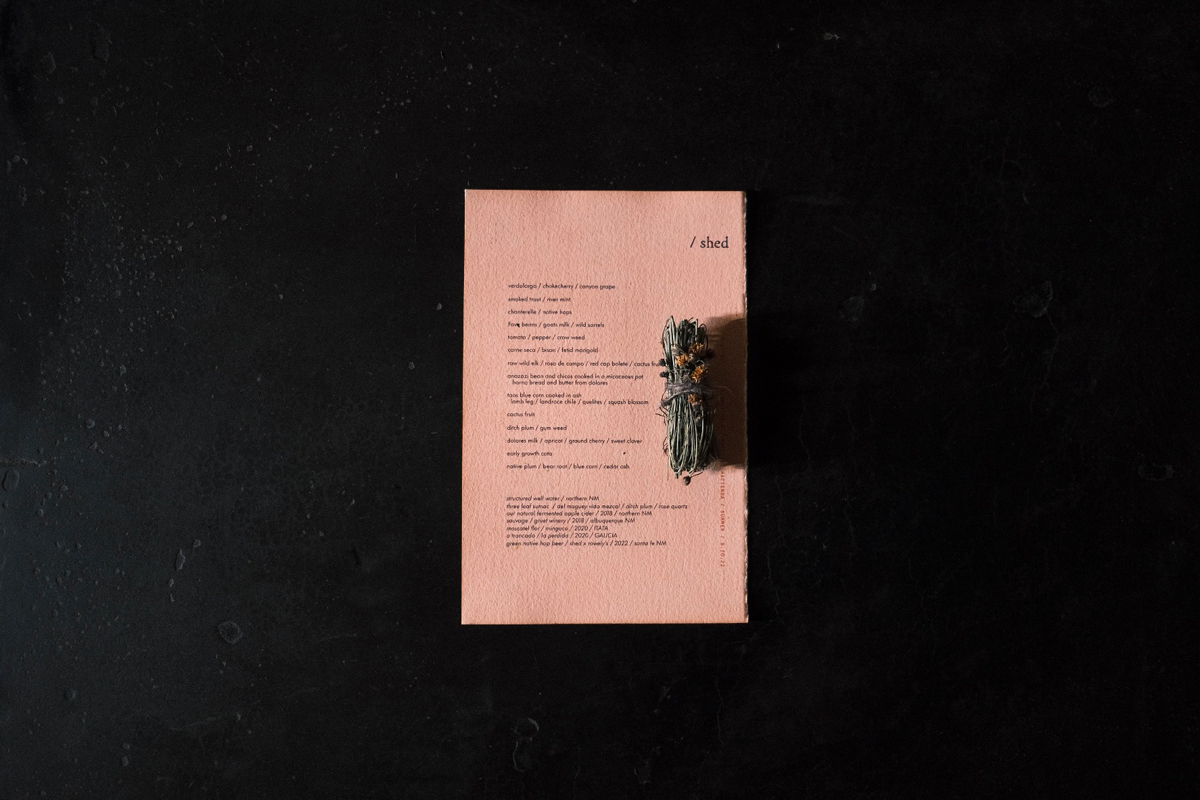

Ortiz-Concha is involved in every step of the process—harvesting nearly all of the ingredients himself. Mule deer. Trout. Chokecherries. Juniper. Morels. Native plums and nettles. Prickly pear and piñon. Red beans and blue corn and cota and osha. Whatever isn’t grown by him and Branch is purchased from local farms. He makes the dinnerware with micaceous clay from the same deposits his Tiwa ancestors have dug for generations, pit-firing pieces on new and full moons.

Branch works with textile artists in her collective, like Suzie Garcia and Josh Tafoya, to dye wool using foraged pigments and weave them into blankets that adorn the dinner spaces. The wool is sheared off their Churro sheep and spun at the nonprofit Mora Valley Mill. She lends her aptitude for film towards anthologizing their work in stirring videos and photos as “a way to share more beauty and a bigger archival project of / shed practices and practices of their ancestors.”

Each detail is carefully considered, imparting a humble sense of reverence. Think wooden spoons hand-carved from non-native trees by Ortiz-Concha’s friend Ron Boyd, dipped into their slow-cooked beans and chile. The first time Branch attended a / shed dinner, she took a bite of this dish and thought, “This says everything I want to say, just in his beans and chile.” For her, it was “the holiest experience.”

We thought creating a system where we could serve the food that we wanted, but also share the inner workings of / shed on a more intimate level, would be a beautiful thing.

The artists they most admire at the moment abide by this practice of reverence in everyday life—familial elders and “the viejos and viejas residing in little valleys of Northern New Mexico.” Branch cites her grandmother and aunt as early sources of inspiration who greatly influenced her sense of composition, lending to her acuity in film and photography. Ortiz-Concha’s grandfather raised cattle at Taos Pueblo, and the remnants of that lifestyle shaped the chef and artist he grew into.

Now, they both find themselves navigating the dichotomies between cultivating success in a digital world and tending to the analog responsibilities of land stewardship. In carrying the seeds of creative traditions, they apply an inventive approach to their own work, efflorescing into contemporary conduits of personal expression and co-creation.

Branch and Ortiz-Concha have conducted nearly one hundred / shed dinners together, in part made possible by their parciante structure. The subscription-based concept had been brewing in Ortiz-Concha’s mind for some time, materializing when he and Branch started collaborating. “We thought creating a system where we could serve the food that we wanted, but also share the inner workings of / shed on a more intimate level, would be a beautiful thing.”

What is a parciante? Named after a community-based approach to tending acequia irrigation systems in Northern New Mexico, an adaptive combination of ancient Puebloan and Moorish infrastructure adopted by Spanish settlers, the existing network of waterways has been in place for centuries, if not longer. Community-governed segments are stewarded by a collective of neighbors—parciantes.

A parciante membership accesses niches of the / shed ecosystem. The mercado (market) is where one can purchase handmade, locally harvested goods like Ortiz-Concha’s ceramics, Churro wool hats and blankets, Criollo beef, and more.

Through recuerdos, they share writing, film documenting their foraging and farming processes, and recipes for nourishments like honey soda or beans and chile. Recently, they launched a live-streamed interview series, the first featuring Nate Ready of Hiyu Wine Farm.

Recolecciones (dinners) are the ephemeral pièce de résistance, what Branch and Ortiz-Concha call the “fruiting body” of / shed’s mycorrhizal practices. Dinners are hosted as pop-up experiences in spaces around Northern New Mexico, such as the historic Hacienda de los Martinez in Taos and the contemporary Sombra de Santa Fe house designed by Dust Architects. The / shed vision is to eventually hold recolecciones in a new space—currently under construction—on the same stretch of land where many of the ingredients are grown.

In order to attend a dinner, one must be a parciante, but can cancel their membership afterwards. Truthfully, this is what I thought I’d do. But upon glimpsing into their world, the fruiting body metaphor elucidated itself, revealing how / shed is so much more than a coveted dining experience. Insights gleaned from Branch and Ortiz-Concha’s recuerdos expose and emotionally tether parciantes to community-driven, land-based lifestyles we should preserve and uplift.

Last year, a friend and I attended a / shed recolección. Of course, we were blown away by the food. But what struck most deeply was how the experience emanated such a genuine expression of Branch and Ortiz-Concha’s beings. Clearly informed by layers of technical mastery, yet seemingly effortless.

How they’re building this ecosystem of care grounded in tradition is a beautiful example of how the future may look if we pose different questions regarding work, land, art, history, and community.

We are multidimensional beings, shaped by the environments we inhabit. In that sense, / shed and Maida Goods exist at the nexus of many different worlds. Sitting at a table placed within this locus feels suspended in time, and leads one to think about the time it takes to develop a mastery of an art form or craft, for a place to feel like home, for friends to become family, to fall in love. And how quickly things can change, whether or not we even realize it.

It’s funny when people are like, ‘back to nature… such a slow-paced life.’ It’s really not. Actually, nature is very fast. It’s constantly reproducing and generating and alive.

In their rural village, Branch and Ortiz-Concha do not exist outside of time, rather, they are governed by a seasonal tempo. Their ecosystem sustains forty Criollo cows, forty Churro sheep, over twenty chickens, seven dogs, two cats, and many bees.

When placing these responsibilities against a clock, time appears more expedited. Branch says, “It’s funny when people are like, ‘back to nature… such a slow-paced life.’ It’s really not. Actually, nature is very fast. It’s constantly reproducing and generating and alive. And even in the winter when things are more dormant, it’s active in this whole other way.”

I recently heard writer m.s. RedCherries (Northern Cheyenne) speaking at a panel, expressing exhaustion in how Indigenous people are too often pigeonholed into simplistic portrayals of romanticized rebellion. She wants her people more accurately represented as flourishing in a state of creation with nuance and complexity.

Have we been socialized to see Indigenous art narrowly characterized by suffering, resistance, and little else? While defiance is necessary in many contexts, what would happen if we shifted perspective, recognized Indigenous art as holistic world-building practices transcending the labels of genre and perimeters of gallery walls?

Part of me still sees / shed and Maida Goods as subversive, punk treatises of resistance in a style very much their own. After all, / shed was named after a Title Fight song. But in Branch and Ortiz-Concha’s shared and individual practices, rejecting norms is only a sliver of what they represent. The most critical task at hand is to engage in an extant practice of envisioning a more beautiful, collective existence, and committing to realizing those values in one’s own life.

Crafting that reality is not without struggle. Ortiz-Concha grew up poor, albeit happy and loved. He worked sixteen-hour days in the seven years he spent honing skills now leveraged towards developing / shed dinners.

Branch grew up in a suburban, segregated Santa Fe. Friends’ parents were unwilling to give her rides home to the Southside—the Brown, working-class side—of town. After graduating from the University of New Mexico, she spent eight years in New York pursuing acting, earning an MFA from The New School, but found it increasingly difficult to fully express herself through her creative work. She returned home to a Santa Fe she hardly recognized.

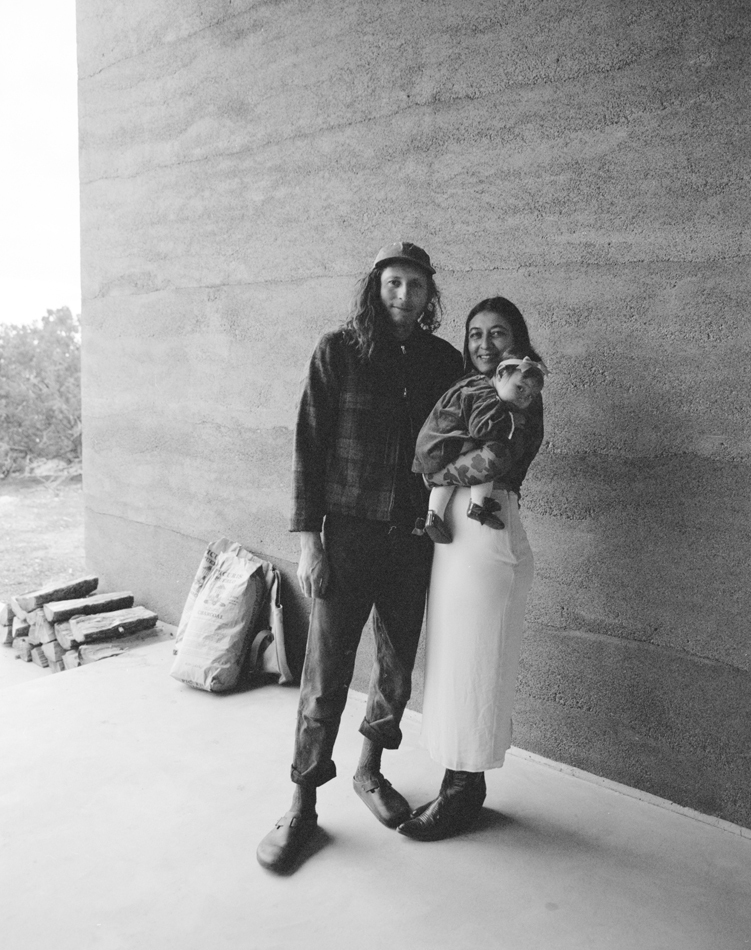

Waves of gentrification in both Santa Fe and Taos meant neither could afford to build the lives they yearned for in the towns that raised them, so instead, they purchased land in a village north of Ojo Caliente. They have worked, and continue to work, tirelessly to create and sustain the magic now enveloping their daily life and rituals. Magic took on a whole new significance when they welcomed their daughter to the world last July. In talking to them, it’s clear they believe everything fell in its right place. But they feel a renewed sense of responsibility to preserve the cultures, histories, and lands that shaped them.

The parciante structure reveals how communalism doesn’t strip away individuality, self-determination, or experimentation—it fuels and sustains it. Humans evolved to be deeply interdependent. We do not have to sacrifice who we are for the sake of a common goal. Indigenous, Chicanx, and Latinx/Hispanic communities do not have to sacrifice cultural identity to earn a living nor mold themselves into the boxes creative industries have long tried to dictate.

Ortiz-Concha often says, “Create the world you wish existed.” Both he and Branch acknowledge that sometimes this means protecting what already exists. She says that maybe “you can’t change the whole world, but you can change your corner of it.” Funnily enough, my own guiding philosophy over the last five years has been “changing the world starts with yourself.” Living in New Mexico, I learn daily how crucial it is to invest our energy in the corners we inhabit, while staying aware of how we are interconnected on a grander scale. To materialize lasting change, first comes the challenging journey of personal metamorphosis.

There are some things over which we are powerless, but where possible, we must be courageous in living our values so we can show others, through example and with love, that another world exists within reach. It’s a tall order, but the magic created as a result is well worth it. Branch and Ortiz-Concha show how self-actualization generates an empowering ripple effect.

After our interview, I took Ortiz-Concha’s advice and stacked my firewood with the utmost care and attempted mastery. Later, I hold the risograph print of the wood stacked in front of their home, which they mailed to parciantes as an end-of-year gift, with a new sense of reverence for this ancient game of Tetris. I marvel at how the threads of time have woven our stories together in this way, all of us storytellers through various media.

Maida and Johnny, lichenous in how they are firmly rooted in the rocky terrain where their families have lived since time immemorial, are vibrant, composite, ever-evolving beings of Indigenous and Hispanic cultures which have made this place so unique, special, and resilient. I am a vagrant counterpart, sans substrate, tumbling with the wind and finding home in new places. Learning every day about where I come from and how that led me here.

Whether cleaning an acequia with neighbors or contributing to the / shed ecosystem from afar, each of us has the opportunity to embody a parciante ethos. For people visiting or settling this land, our liberty of movement comes with a special responsibility—to walk a path of respect, humility, care, and reciprocity toward those who strode before us.