The World Outside: Louise Nevelson at Midcentury at the Amon Carter takes a fresh look at the influential artist through a historical lens, and argues that the world shaped her.

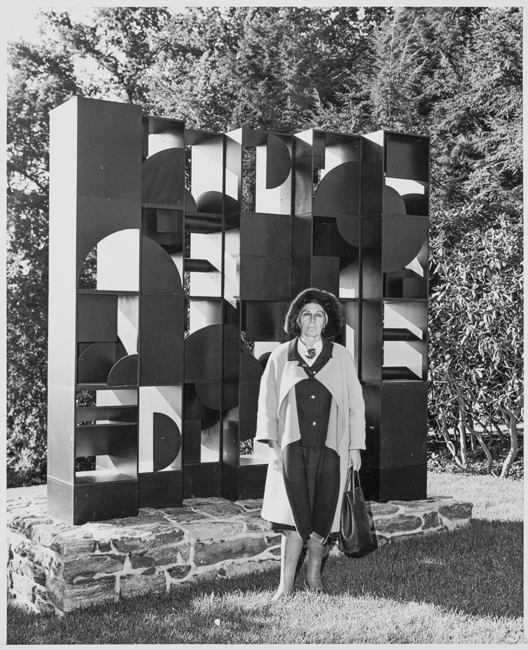

FORT WORTH—The late Louise Nevelson was a revered sculptor whose abstract, monochromatic artworks made of repurposed wooden objects helped shape the artistic landscape in the mid-20th century. She was collected by major museums worldwide and selected to represent the United States at the 1962 Venice Biennial. The Ukrainian immigrant who lived most of her years in New York City was a pioneering feminist artist who defined how public art was displayed. She also made a mark in the Land Art movement and influenced later generations of artists.

By the time she died in 1988, as art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson, author of the recently published Louise Nevelson’s Sculpture: Drag, Color, Join, Face, said in a recent Literary Hub interview, her obituaries frequently were “more about her makeup and attire than they [were] about her towering achievements in sculpture.”

Nevelson, whom writer Jon Raymond described as “under-understood,” is again getting her due, thanks to Bryan-Wilson’s monograph, recent exhibitions in Berlin and Los Angeles, and a show currently on view at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth.

The deeply researched and deftly argued The World Outside: Nevelson at Midcentury at the Carter includes fifty sculptures and works on paper. The works on view illustrate that the eccentric pioneer in sculpture and assemblage was aware of the world around her, a compliment for a woman in a man’s game.

The exhibition title takes its name from a theme from Nevelson’s 1943 show Circus: The Clown is the Center of His World. The theme was, in fact, The Crowd Outside.

Whether the attribution was a mistake, the description fits her practice, according to Shirley Reece-Hughes, curator of paintings, sculpture, and works on paper at the Amon Carter Museum.

“She cultivated a sort of Gothic persona. But we must think about the era in which she was working, the post-war era when men ruled the art world,” Reece-Hughes says. “Sculpture was a domain of men; women were not allowed to go into that realm. There was so much gender and societal conformity.”

“Nevelson,” Reece-Hughes says, “works against that tide.”

Her participation in modern dance and her love of choreographer Martha Graham, as seen in the black abstract sculpture Martha Graham (ca 1950) and early sketches, are the earliest suggestions of how Nevelson bridged her interests with her art.

“Dance was a radical form. She was deeply inspired by that,” Reece-Hughes says. Nevelson’s intense, decades-long studies gave her a depth of understanding of musicality and rhythm, seen throughout her career.

She was also inspired by political, social, and intellectual developments at the time, which coincided with trips to Mexico in 1950 and 1951 and her time living in Rockland, Maine. These experiences shaped her thinking about the relationship between community, ecology, and the built environment. But as her dealer Arnold Glimcher wrote in his 1972 book Louise Nevelson, her personal and professional lives were inseparable. She didn’t need a diary to document her thoughts; she had an art career to figure them out.

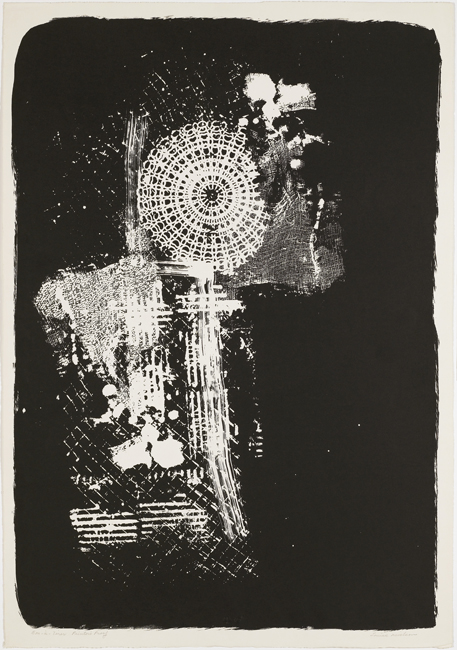

Other professional challenges and experiments came from her time studying printmaking at Atelier 17 and, later, Tamarind Printmaking Studio, then in Los Angeles, where she produced many of her works on paper. One untitled lithograph from 1967, again, incorporates non-traditional materials such as cheesecloth. (All prints are untitled, and unlike her sculptures, Nevelson left abstract figures in her prints, allowing viewers to ponder ideas. These works were “portals” to somewhere else.)

The ethereal was as tethered to her work as social movements and her convictions. In prints and sculpture, she frequently evoked the heavens and earth, such as in the works Night Landscape (1955) and Lunar Landscape (ca 1959-1960).

To Reece-Hughes, these titles reflect the space race, where the United States and then-Soviet Union competed to be the first to go to outer space. But, she says, “She also wanted a connection between the everyday and transcendental.”

Other sculptures contributed to her interest in “how systems are connected between humanity and nature.” She tested that intersection in 1959 when she debuted Dawn’s Wedding Feast at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. She would later describe the sculpture and future wall-size works as “living communities,” where the audience engaged with the objects. They were a celebration of community. Using salvaged wood from remaining scraps was a reclamation of the past.

Relationships between nature and humanity evolved with the sculpture Rain Forest Column XXXI (1967), an attempt to show how rainforests help us think about ecosystems and a call to arms about the dearth of natural resources.

“The study of ecology was just beginning to become a serious field of study,” as well as an activist field, Reece-Hughes says, “and she was active in the intellectual foray.”

She placed herself as an active environmentalist and land artist while remaining a minimalistic public artist.

“She was ahead of our time because minimalism becomes so much about modularity, like with Donald Judd or Tony Smith. The idea of site-specific installation and visitors’ participation is something artists do today,” says Reece-Hughes, who mentions Brooklyn artist Leonardo Drew, who cites Nevelson as an influence. Drew’s site-specific Number 235T (2023) is on display at the Carter until June 2024.

Reece-Hughes’s passionately curated show drives home her point: Nevelson was a multi-faceted, complex artist who was intuitive about what was happening in the country in the mid-20th century.

“She lived through dramatic changes in American society and economics,” she says. Going through similar moments now, “I thought it was a critical moment instead to reclaim her contribution to American art history.”

Correction 09/23/2025: An earlier version of this article stated that Nevelson lived in Rockport, Maine. She lived in Rockland.