Keith Haring was a Phoenix teacher’s second choice for a 1986 art workshop, but the invite made a major mark on the city.

PHOENIX—Today the streets of Phoenix are dotted with murals painted by local and international artists exploring a broad range of themes from Indigenous histories to climate futures.

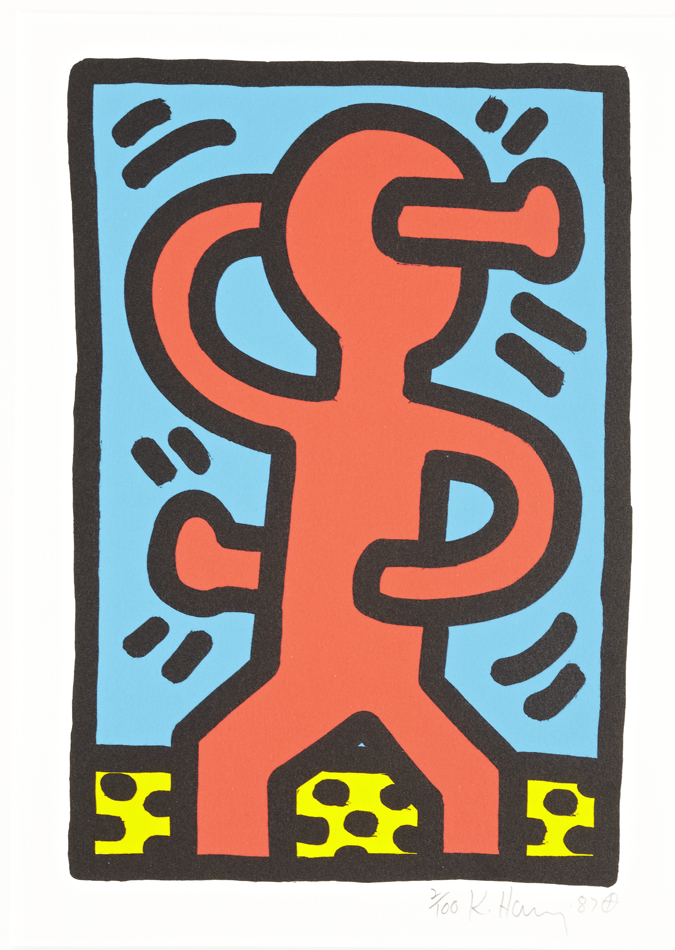

But that wasn’t the case in 1986, the year that renowned artist Keith Haring did a drawing workshop at Phoenix Art Museum, then collaborated with students from a South Phoenix high school on a mural project that created ripple effects within the city’s emerging arts scene—including the new exhibition The Collection: Keith Haring at Phoenix Art Museum.

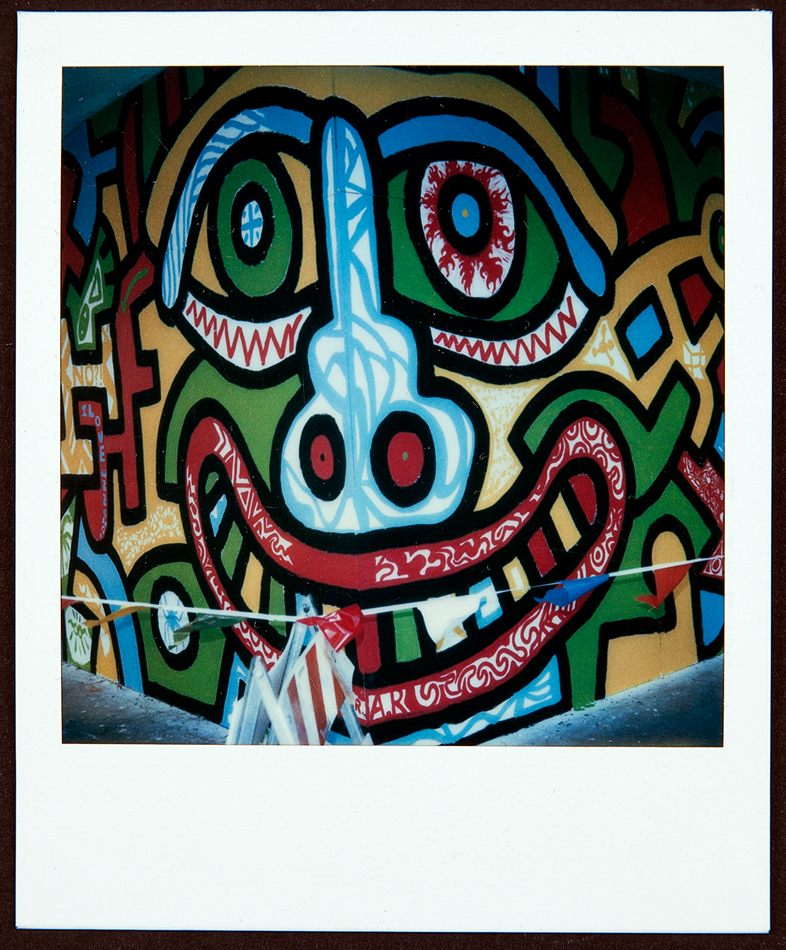

Such Styles, an artist who’s part of the pantheon of early graffiti writers in metro Phoenix, was just sixteen years old when he met Haring at the museum workshop that year.

“There were only a handful of graffiti writers around Phoenix back then, and I was just coming up through the ranks,” says Styles, who was attending Marcos de Niza High School in Tempe at the time.

Styles remembers striking up a conversation with Haring near a long table covered in paper where students were making marks inspired by both Haring’s distinct doodle-like graphic imagery and their own visual vocabularies.

As it happens, (Haring’s visit) nearly didn’t transpire.

“I’d just read Getting Up: Subway Graffiti in New York and Haring was one of the iconic artists in the book so I was really excited to talk with him during the workshop,” says Styles, who’s since become one of the region’s most prolific muralists, often working with his son and fellow artist Champ Styles.

Styles’s voice quickens with exuberance when he talks about Haring, describing him as “our beloved Keith.” Styles recalls Haring drawing a dancing dog inside his jacket and a stack of characters inside his “black book” graffiti sketchpad that day.

Styles recounts Haring wondering where he could find the city’s arts scene, and remarking on the lack of graffiti in Phoenix.

At that point, First Friday art walks and other traditions that anchor the mainstream art scene today didn’t exist.

Styles told Haring about some of the sites where local writers would “go bombing” along freeways and railroad lines, even inviting Haring to come along.

That didn’t happen, but Styles still felt respected by Haring—and says the artist’s approach continues to inspire the way he works with students in various arts programs.

“He was so chill, really quiet, and very, very approachable,” Styles says of Haring. “As graffiti writers we were colleagues—he really made me feel that way.”

As it happens, their encounter nearly didn’t transpire.

That’s because the art teacher who helped bring Haring to Phoenix was originally trying to arrange a student workshop with a different artist.

Ceramicist Mike Prepsky was helping to launch a magnet arts program at South Mountain High School at the time and hoped to bring artist Jonathan Borofsky to town.

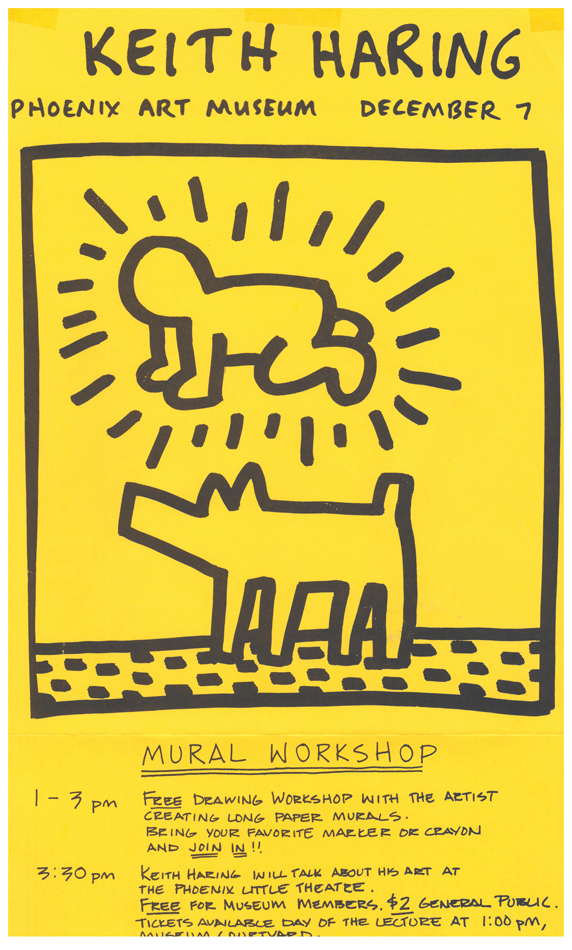

When Borofsky wasn’t available, Bruce Kurtz suggested they reach out to Haring. Kurtz was the museum’s curator of 20th-century art back then, and Prepsky was an educational trustee. Sure enough, Haring did the workshop. But his time in Phoenix didn’t end there, because Haring decided he wanted to do a student mural project.

That meant key players, including city officials, had to scramble to make it happen. The project came together on a building at Central Avenue and Adams Street, not far from the city’s convention center.

The fate of Haring’s Phoenix mural remains a mystery.

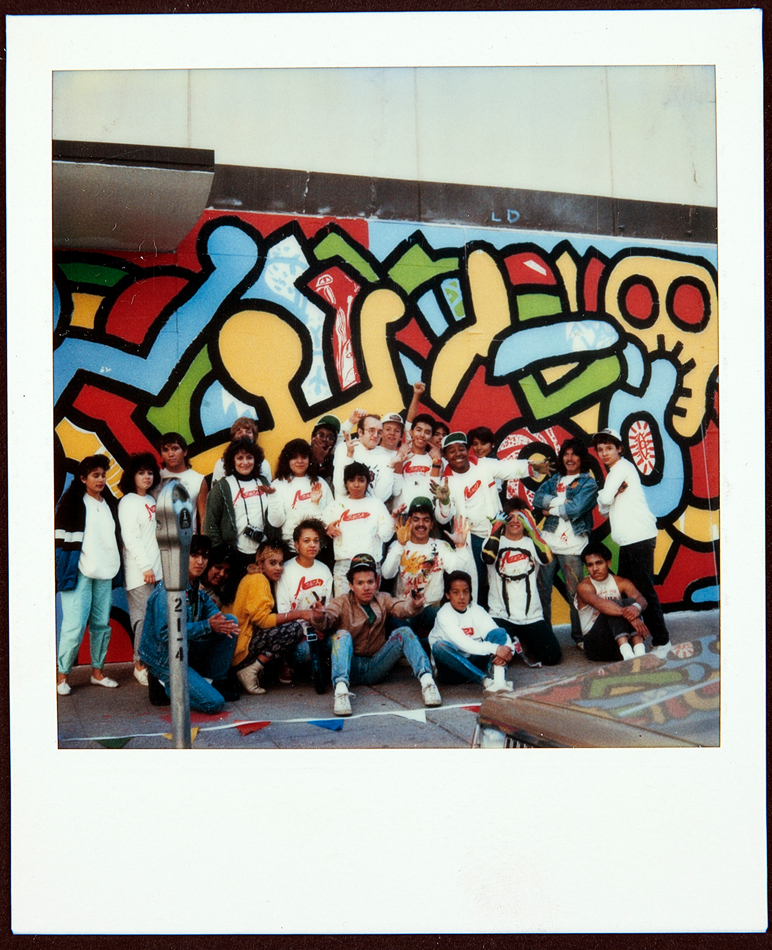

Dozens of South Mountain High School students took part, painting on wood panels installed along a wall measuring 150 feet long, Prepsky recalls.

On day one, Haring spent a couple of hours doing an impromptu design with black paint and a two-inch brush as the youth looked on. Then students spent several days filling in colors and adding their own spontaneous doodles.

“He was very kind and never looked down on the students,” Prepsky says of Haring. “He had the spirit of a child, with so much energy and imagination.”

That same year, Haring painted his famous Crack is Whack mural that still stands along FDR Drive in New York City—and he opened the NYC Pop Shop where merchandise like buttons and t-shirts made the artist’s work accessible to a lot more people. Just months before, Haring created a mural on the Berlin Wall, which was destroyed when the wall came down in 1989.

The fate of Haring’s Phoenix mural remains a mystery.

“The mural was only supposed to be up for a year, because the building was going to be demolished,” explains Prepsky. But redevelopment plans changed, and the mural remained up for about five years before the city removed it. By then, the house paint Haring used was peeling, the mural was dirty, and the artwork had been tagged. Supposedly, the city hauled the wood panels to the city dump, but rumors of subsequent panel sightings persist.

The mural was still on view in February of 1990, when Haring died of AIDS-related complications at the age of 31.

In 1992, Phoenix Art Museum originated an exhibition of work by Haring, Andy Warhol, and Walt Disney, with a catalogue that features a photograph of the full mural that people can still see online.

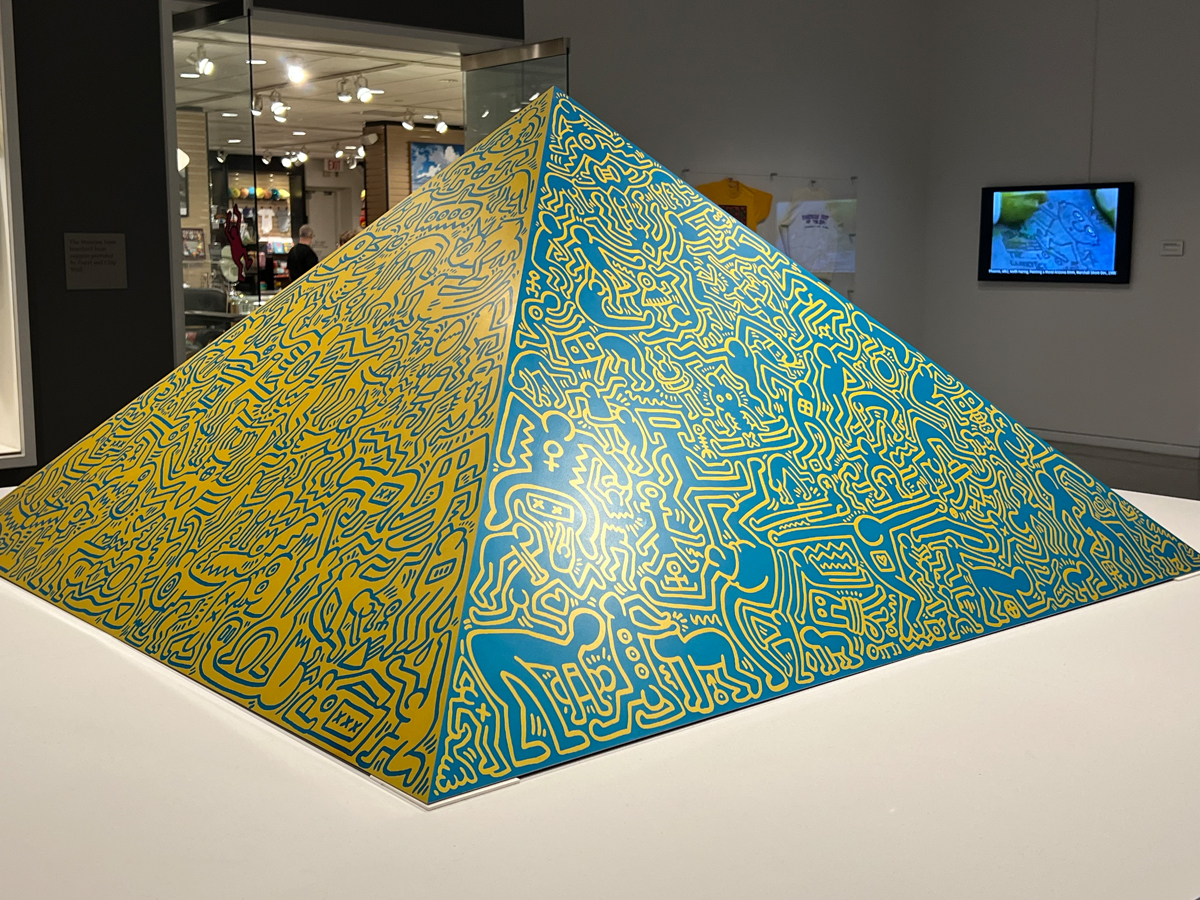

Today, video footage of Haring painting with the students is part of The Collection: Keith Haring, an exhibition at Phoenix Art Museum that opened on December 7, 2024, and continues through July 20, 2025. The installation includes archival materials and ephemera from Haring’s time in Phoenix, along with artworks by Haring from the museum’s collection.

“It’s so great to see Haring creating the artwork with the students,” reflects archivist Aspen Reynolds. “It was a time in the Phoenix community when the arts were still budding, and it’s cool that we had such a big artist visit the museum and the city.”

Christian Ramírez, the museum’s curator of contemporary and community art initiatives, organized the installation along with Reynolds and interpretations manager Charlotte Quinney.

Prepsky sees the ripple effects of Haring’s time in Phoenix beyond the museum walls, in works by artists like Tato Caraveo, a former student at South Mountain High School whose surrealistic murals abound in the city’s Roosevelt Row arts district.

“It would be awesome if we could still see Haring’s mural,” says Ramírez. “But even though it’s not there anymore, its impact is still there.”