I grew up on a ranch in the Texas Hill Country and spent as much time outside as possible. There were old roads, stone fence lines, ruins of buildings, and archaeological sites that stretched from creek beds to groves of trees. I would hike up hills and look out over the landscape, seeing patterns of agricultural fields, highways, and windmills. Later, as a young archaeologist, I explored the prehistoric landscape along the Mimbres River near Silver City. Roads and buildings aligned to the river were still evident in the landscape. To me, the landscape could be read as a story, with mysterious layers throughout, speaking of the people who lived there before. It wasn’t until my graduate studies in landscape architecture at the University of New Mexico that I had a name and concept to finally give to my landscape wanderings: cultural landscapes.

Jackson closed out the twentieth century with a more honest, comprehensive, and grittier look at the American scene, much of which was inspired by and derived from the landscape of New Mexico and the West.

Landscape writer J.B. Jackson created a foundation in cultural landscape studies for me and many others through his copious, sometimes rambling works on the field. A Sense of Place, A Sense of Time (1994) is a musing on American cultural landscapes—from ruins to trailer parks, wilderness to gardens, churches to plazas. The first essay opens with a photograph of Los Angeles parking lots taken by Ed Ruscha in 1967. Use of an image of the common and urban demonstrates how landscape studies had evolved over the twentieth century, due in large part to Jackson’s work. Growing from previous centuries’ understandings and definitions of landscape, which were tied to paintings and the romantic picturesque, Jackson closed out the twentieth century with a more honest, comprehensive, and grittier look at the American scene, much of which was inspired by and derived from the landscape of New Mexico and the West. This is the landscape I related to as a child and young adult—that of the vernacular and the everyday.

Born in 1909 to American parents in France, John Brinckerhoff Jackson had a privileged upbringing, attending boarding schools in both the United States and Europe. As a young man, he traveled far and experienced different cultures, carrying a sketchbook to record his perceptions of the vastly different places he visited. Despite some early literary success just after college, Jackson returned to New Mexico, where he had first visited as a child in the 1920s. In New Mexico, he spent time working on a ranch in the vast sky-filled landscape near Wagon Mound before enlisting in the Army in 1940. Jackson returned to the United States following the war and began honing his perceptions of the American cultural landscape and broadening his time and experience in New Mexico. By 1951, based in Santa Fe, Jackson started Landscape, a magazine that he managed as editor and publisher until 1968.

Landscape magazine provided Jackson with a platform for exploring current and expanding topics on the environment. Jackson often created much of the content but also relied heavily on a growing network of professionals in the increasingly allied fields of geography, architecture, landscape architecture, anthropology, and others. During this time, Jackson also began lecturing and teaching on landscape issues, traveling across the country by motorcycle from Harvard University to UC Berkeley and many places in between. Jackson came into contact with geographer Carl Sauer at Berkeley, who created the first cohesive definition of a cultural landscape. Jackson, through his cross-country teaching and lecture circuit, expanded on Sauer’s ideas and shared them with architecture and design students and faculty. Also, under Jackson’s influence, cultural landscapes studies became increasingly tied to historic preservation efforts, giving preservation professionals a comprehensive way to better understand both spatial and temporal layers of place. A Sense of Place, A Sense of Time, written towards the end of Jackson’s long career, gives us a glimpse into his multivalent view of the American cultural landscape. From understanding the environment through perspectives on wilderness and vegetation to the garden, roads, buildings, and the way humans make and understand their environment, Jackson wove often-overlooked evidence in the American landscape into a comprehensible space with a rich and textured history.

So, what exactly is a cultural landscape? A Sense of Place, A sense of Time is a poetic introduction to the field and way of seeing places. Each essay gives the reader a glimpse into the complexity of landscape histories, taking aspects of a cultural landscape worthy of exploration. Beyond Jackson’s writings, cultural landscapes are often defined by who you are and where you live. The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) World Heritage Convention loosely defines a cultural landscape as the combined works of nature and humankind that express a long and intimate relationship between peoples and their natural environment. The National Park Service (NPS) has a similar but more detailed definition, stating that the cultural landscape is a reflection of human adaptation with the natural environment as the framework from which it evolves. The NPS, along with UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention, has created a methodology for the documentation, listing, and protection of designated cultural landscapes. The NPS recognizes four types of cultural landscapes: the ethnographic, the vernacular, the designed, and the historic site. These types are not mutually exclusive; often complex landscapes, like those of New Mexico, will be a combination of the four through both time and space. The NPS uses thirteen landscape characteristics to analyze a given cultural landscape. These range from topography, natural systems and features, vegetation, buildings and structures, and archaeology to spatial arrangement and cultural traditions. These characteristics were meant to help the NPS understand both processes and objects in a landscape and how they have evolved over time. Again, these are not meant to be mutually exclusive but act as a set of thinking tools about a place of historical significance. Cultural landscape studies within the NPS reside in the realm of landscape architecture and historic preservation, as influenced by Jackson.

Cultural landscapes also reveal layers of time. New Mexico, with its visible ruins, both historic and prehistoric, reads as a continuum with clear evidence of the multicultural place it is.

What does the cultural landscape concept help us actually see in a place?

Arguably, everything is a cultural landscape. Jackson attempted to see as much as possible, using New Mexico as a starting point and always returning to its complexities. To start, the cultural landscape concept helps us better see the natural world around us. Even in the most urban of settings, it is there: a blade of grass, a street tree, the ground we walk on. The concept provokes questions about how landscape was altered. In the midst of Manhattan, the cultural landscape is thickly apparent through its grid, its architecture, its streets, its people, and its views, with Central Park as a rich reprieve in the middle. The natural topography and geology of the park is evident, with manipulations by Vaux and Olmsted, that create one of the most culturally iconic landscape experiences in the world. The cultural landscape concept also reveals systems such as seasons, climate, and human participation in these events. Japan is the master of this type of experience, through deep cultural celebrations of seasonal changes such as plum and cherry blossom viewing festivals and long walks under red maple leaves in the autumn. Cultural landscapes also reveal layers of time. New Mexico, with its visible ruins, both historic and prehistoric, reads as a continuum with clear evidence of the multicultural place it is. Santa Fe gives us a layered view, from mountains to plaza, old homes and new, and hiking trails tied into the Camino Real.

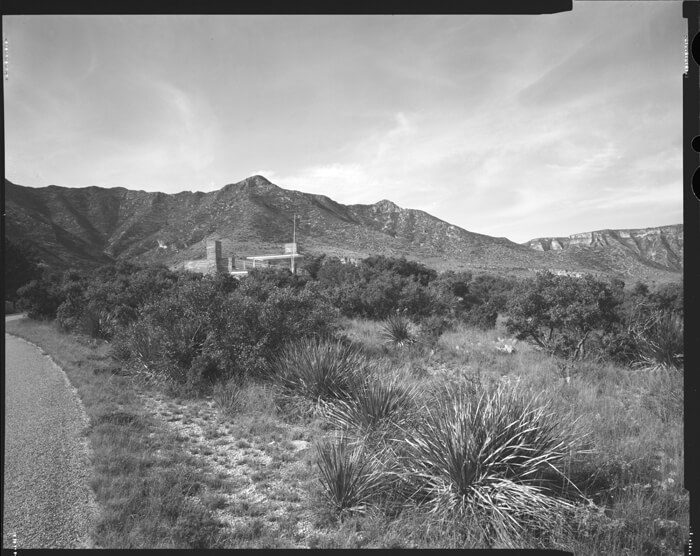

When we visit places, we are looking at a cultural landscape. The NPS has documented these for management and preservation purposes. Every park unit will have at least one cultural landscape that, tied to historic or prehistoric importance through its association with specific people, events, design, or ability to yield further information, may be interpreted for visitation. Park units in New Mexico, such as Pecos National Historical Park, Bandelier National Monument, and the newly created Manhattan Project National Historical Park are close to Santa Fe, and the cultural landscapes of these places are rich in prehistoric through recent history that is still evident in the landscape. Further afield, Carlsbad Caverns National Park and neighboring Guadalupe Mountains National Park (just across the New Mexico/Texas State line) are both known for their natural beauty. However, both parks contain multi-layered cultural landscapes. These include landscapes tied to the Butterfield Overland Mail route, the Apache Wars, ranching, and park development. Carlsbad Caverns is currently documenting the early-twentieth-century cavern trail system (inside the main cave) as an underground cultural landscape. Guadalupe Mountains National Park is working to preserve the legacy of Wallace Pratt, an early oil man in the area. Pratt’s land (most of McKittrick Canyon) was a gift to the NPS and the impetus for the creation of the national park. The land is not only known for its outstanding geology and ecosystem but also for Pratt’s two homes, one of which is an early modernist building called Ship on the Desert, which is perched high on a ridge overlooking the Permian Basin.

Beyond the NPS, there are countless cultural landscapes to explore in the Southwest. Near J.B. Jackson’s home in La Cienega, El Rancho de las Golondrinas is a living history museum and cultural landscape where processes such as use of the acequia system for agriculture and sheep shearing, wool dying, spinning, and weaving are still practiced. Using the NPS category of the “designed” cultural landscape, Paolo Soleri’s Arcosanti in Arizona and Walter De Maria’s Lightning Field near Quemado, New Mexico, are outstanding examples of altered landscapes for design and art. In Marfa, Texas, the minimalist artist Donald Judd created his fifteen untitled works in concrete between 1980 and 1984. The concrete sculptures stretch out straight along the Chinati Foundation’s edge for roughly half a mile. Judd’s work built upon the ruins of a U.S. Army fort, altering existing buildings and landscape for his sculpture and design in an effort to create a cohesive vision of place. Beyond Judd’s landscape, Marfa can be seen in the distance: the water tower, the Presidio County Courthouse, residences, roads, and the Chihuahuan Desert. A West Texas ranching town and an artist—Marfa and Judd—reflect a cultural landscape extended.

J.B. Jackson looked upon the whole American scene as original. Guided from his home in La Cienega, Jackson made sense of landscapes around the United States for several generations of young designers, including those at the University of New Mexico as Jackson helped start the landscape architecture program there. Jackson saw layers, culture, objects, and processes. He understood and wrote about the interaction of humans and their landscape over time. Jackson also worked in the landscape of New Mexico, choosing manual labor over a purely academic lifestyle. He joined the local Catholic congregation. He took part in the New Mexico around him, writing on landscapes until his death in 1996. New Mexico helped foster this in Jackson. It was a place to think, a place to write, a place where he could look out and see active human environments, ranging from the ordinary and vernacular to the extraordinary and breathtaking—contrasts everywhere. Ultimately, cultural landscapes can stretch out as far as we need or want to see them. They connect space, time, history, and nature. J.B. Jackson wrote that New Mexico is “a landscape with a history that is perhaps not a history at all, merely the unending repetition of cosmic cycles…” Perhaps this is a way to see and understand cultural landscapes and certainly the sublime landscapes we have to explore.