In the center of the Santa Fe Plaza, a concrete obelisk looms 33 feet high. The structure, a monument to Union soldiers (described as “heroes”) who fought in Civil War-era battles against “savage” Indians, was erected in 1868. Save for an unknown person chiseling out the word “savage” in 1974, it has remained unchanged as the centerpiece of the city for 152 years.

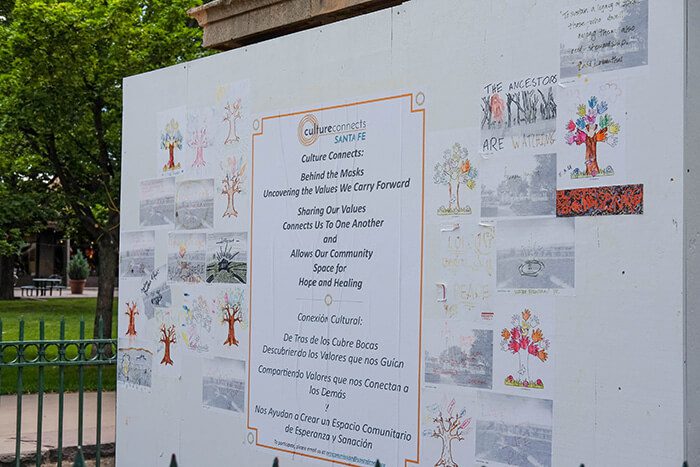

In the weeks since the murder of George Floyd and the ensuing demonstrations for Black Lives Matter, dozens of monuments and statues that pay homage to this country’s racist foundations have been removed, or ordered to be removed. The obelisk is included in the latter group—instead of proceeding with an immediate removal, the city tasked its Arts and Culture Department to take an alternative approach. The obelisk is now encircled by an eight-foot plywood wall, and residents are invited to “write or draw messages of reconciliation, of healing, of hope, and love,” said John Muñoz, the city’s director of parks and recreation. The project is called “Culture Connects: Behind the Masks—Uncovering the Values We Carry Forward.”

“We’re hoping that this gives us time to have a discussion on where in history this monument belongs and what it means for the community of Santa Fe,” said Muñoz. Some options include taking down the monument in pieces, removing the plaques and replacing them with a different message, or leaving the obelisk where it stands. “It’s a community discussion,” Muñoz continued, “and a decision that our leadership will make.”

While many residents are participating in the project by creating poems and artworks for the canvases, and celebrating the opportunity to reconcile with a racist symbol and history, some consider the project to be artwashing an important political movement.

“You can put lipstick on a pig, but at the end of the day it’s still a pig,” said Dr. Christina M. Castro, co-founder of the grassroots organization Three Sisters Collective. “We got the assurance from the mayor that the removal was going to happen [and] we’re hoping that those steps are being actualized […] because [the monument] is problematic and it’s going to continue to be problematic until it’s gone.”

“Public symbols are powerful, and every day that they continue to occupy public space, their power persists.”

In late June, red handprints and splashes of red paint appeared on the monument overnight, and the city power washed the paint off shortly thereafter. Castro noted that this should be perceived as public art in its own right. “In a city that has capitalized so much on Indigenous American Indian art, it’s indicative that they can’t see that artistic display for what it is. […] It shook them to their core. More than the bodies of missing murdered Indigenous women,” she said. “That’s the power of art. Real art, the way Indigenous people see our art.” A few days later, the obelisk was spray-painted with phrases such as “Tewa Land” and “genocide.” The community response, again, was immediate: Santa Fe Crime Stoppers offered a $1000 reward for information leading to arrest.

In response to accusations of artwashing, Muñoz explained that the project was conceived both as a way to create time to plan for the obelisk’s future, but also to create a venue for discussion and to model creative approaches to issues around public symbols. “It’s a very complex issue with a lot of emotion on both sides. For us to move forward and to mature as a nation we do need to have this important discussion—that’s what it is, a discussion, debate.” The city is particularly encouraging young artists and poets to participate in the project. “That’s a key ingredient here, because that’s our future,” Muñoz emphasized.

But as Castro said, public symbols are powerful, and every day that they continue to occupy public space, their power persists. Santa Fe, a town that profits on its persona and the trappings that accompany it, knows the value of symbols better than most. “This is a town that prides itself on art and culture,” said Castro, “but they want it sanitized. They don’t want our real story.”